|

Time

Out

The great Armenian Chess

Kajalie

Shehreen Islam

Some players

have the almost inexplicable ability to win a game without

doing anything whatsoever. They spot 'negligible' positional

inaccuracies and outplay the opponent, usually in a long game.

Little fireworks, and no crowd-pleasing business!

These

players know very well that an attacker will cross the limits

of safety or lose patience in the face of a dour defence.

From the point of view of chess, their play is based on the

notion that an over-extended, broad structure has its weaknesses

too. It may not be easy to maintain coordination among your

pieces, particularly when they have advanced deep into the

enemy territory but are not very effectively placed. This

may be called pseudo-development or deployment.

Modern

chess theory treats the concept of development a bit differently.

It's not enough to develop your pieces; the most important

thing is whether they are working in perfect harmony with

each other and creating lethal threats. Else, they will have

to retreat at some stage, losing valuable time.

One modern

player whose play had a truly mystic quality was Tigran Petrosian

(world champion 1963-69). Petrosian had a style not easy to

describe. He would follow the opening theory, like most others,

but in the early middle game, he would invariably start a

regrouping which often appeared to be rather enigmatic. A

chess commentator once said, "Petrosian can be dangerous

from the back rank". That defined the Armenian world

champion's original style and ideas in one sentence.

As a

player, he was often misunderstood for two reasons. First,

his subtle play did not have much appeal to the average chess

fan. Even a master of Rueben Fine's stature described Petrosian

as the weakest ever (!) world champion. Second, Petrosian

came under the shadow of Bobby Fischer who was playing marvellous

chess in the sixties. I think Fine did gross injustice to

the player who added an altogether new dimension to the game.

There is no doubt that Petrosian's play enriched chess in

many ways.

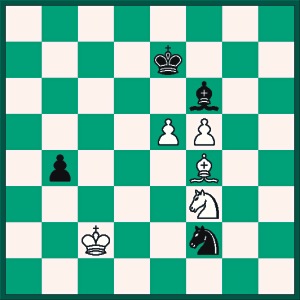

Here

is a game that he won against Ludek Pachman, the German player

and theoretician.

White-

Tigran Petrosian

Black-Ludek Pachman [A07]

Varna Ol (Men), 1962

1.Nf3

d5 2.g3 g6 3.Bg2 Bg7 4.d3 e5 5.00 Ne7 6.c3 00 7.Nbd2 c5 8.e4

d4 9.cxd4 cxd4 10.Nc4 Nbc6 11.a4 Be6 12.b3 f6 13.Bd2 Nc8 14.h4

h5 15.Kh2 Nd6 16.Bh3 Bg4 17.Kg2 Qd7 18.Bxg4 hxg4 19.Nh2 f5

20.Nxd6 Qxd6 21.b4 Nd8 22.b5 Rc8 23.a5 Rf7 24.Qa4 Rfc7 25.h5

Qe6 26.hxg6 fxe4 27.dxe4 Qxg6 28.Rfe1 Rc2 29.Ra2 Rxa2 30.Qxa2+

Qe6 31.Qxe6+ Nxe6 32.Nxg4 Rc5 33.Rb1 b6 34.axb6 axb6 35.Kf1

Nc7 36.Ke2 Rxb5 37.Rxb5 Nxb5 38.Kd3 Kf7 39.Kc4 Na3+ 40.Kb3

Nb5 41.Kc4 Na3+ 42.Kd3 b5 43.f4 exf4 44.gxf4 Nc4 45.Bc1 Ke6

46.Nh2 Kd6 47.Nf3 Kc5 48.Ng5 Kd6 49.f5 Ne5+ 50.Kxd4 Ng4+ 51.Kd3

b4 52.Kc2 Bf6 53.Nf3 Nf2 54.Bf4+ Ke7 55.e5 b3+ 56.Kxb3 Nd3

57.Bg3 Bg7 58.Bh4+ Kd7 59.f6 Bf8 60.Kc4 Nf4 61.Bg5 Ne6 62.Kd5

Ba3 63.Be3 1-0.

Position

after 55.e5

-PATZER

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|