Special Feature

“To sir, with love”–

Kibria: Immortal in our hearts

Fayza Haq

|

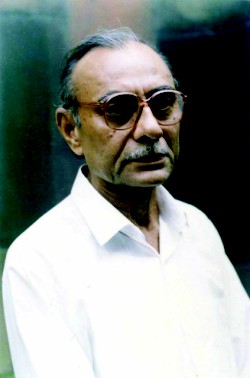

Mohammed Kibria, an undisputed legend. |

Mohammed Kibria, superb teacher of prints and nonpareil guide of painting, will remain an undisputed legend. Self effacing, often sporting long “kurtas” and thick glasses, he was a man of few words – but remained witty and marvellously subtle. With a single clever comment he could put abrash, pompous student in his place. His eyes glanced and studied his student's work – and he guided each in an unforgettable way. He just glanced at each piece of work, which his students rushed forhim to see. He would say “Add a line here” or “Put some darker shades here”, and so put his magic touchto every student'spiece of work. He loved and cared for each student of the Institute of Art, DU. Gentleand soft-spoken,he was like some veritable guardian angel who walked this earth, showering each art student with understanding and kindwords of meaning – which each artist who came his way would treasure in his heart..

Sitting cosy on a rain-drenched day, seven artists of repute spoke out their passionate feeling for a father figure – who will remain immortal in their hearts.

He was a man of few words says Hamiduzzaman Khan. "He was very gentle. I was in the Art College since 1962. That batch had him from 1964-65. He and Safiuddin Ahmed were my first teachers. We were told earlier by Zainul Abedin, earlier on, there was a work of his in the print-making department. It was an abstract piece; it had black andwhite lines all over. Incidentally, I was a third-year student then. Our teacher Abedin 'sir', as we put it, taught us to admire that piece. Since then I learnt to appreciate and admire him. When he returned from Japan, he took a class in lithography, in which the work is done on stone. I did a portrait drawing from a model in classroom. Seeing it Kibria 'sir' was very pleased. I was sitting on a bench and working with black ink and pen. He worked on my piece for a minute or so, and the portrait came to life. For me this was like magic. I was told to transfer it to print and the picture was a fine one: A copy of this still hangs in theprint-making section. When a picture is considered a very special, it is given a permanent place on the wall.

From that time, my connection with Kibria developed and grew with time. He was staying in the Students' Hostel near New Market with other students like myself. Samarjit Rai Chowdhury shared a room with him. We had a central bathroom and we often found him quietly waiting there for his turn. Each day, as students, we had him in our lives. He was like a guardian for us. When we returned with our daily exploits, Samarjit Rai and he called us to examine our sketches like some 'senior' friends. Our relationship was an informal one. When I became a teacher myself, by that time Kibria 'sir' had got married and had left the hostel after the Liberation in 1971. Kibria 'sir' was very close to Samarjit and together we often discussed him. Kibria sir had close contacts with students and teachers around him. By 1955 the enclosing building of 'Art College' had been completed. The different departments, in the beginning, were adjacent to each other at that time. The teachers, at that time, missed no class.

Just as they collectedboth the paintings and drawings of the master artist Ramkingkore and exhibited withcare,theworks of our pioneers of fine arts deserve a specialplace of display,so that they remainwithin the country, to see, admire, and learn from. The governmentcould take the initiative for this. This was essentially the task of the Shilpakala Academy. As far as possible, the worksof Kibria and Safiuddin should be preserved forall generationsto come. True, the government ahs awarded him the 'Ekushey Padak' and the 'Shadhinata Padak', while Kibria was ill for ages together in the recent part, he wasn't looked after on the government level.

Today, we feel a great emptiness in us – with Kibria's departure; and another guardian, Shafiuddin indisposed. This is the end of an age.

Says Ivy Zaman: "I came to the Art College in 1974; in print-making, I got to learn from Kibria and Safiuddin. This was for other students, too, to some extent or more. His gentleness also gave us strength. He was never embroiled in other matters. He remained in his own world, the worldof art. I wish, like Hamid, that an art museum dedicated to him were established – even if it were only in the premises of the Art College.

|

The artist at work. Photo: courtesy |

"I would like to talk about Kibria – as a teacher.A master is more than just a teacher – he knows that each student is different ; and treats each individually. He never thrusted his ideas on others. He was my guru. I'm in the art worldbecause of him, and him alone,” says the emotionally-chargedand deep thinking Ahmed Nazir, one of the directors of gallery Chitrak.

Fiery and flamboyant youngprofessor Nisar Hussain says, “Kibria has been given all the majornational awards. A country which cannot provide the necessary food,clothes and shelter – the primaryneeds of man, in such a country it is amazing how far fine art has reached. The fact that the country as a whole admires and respects an artist is something great on its own. To get the highest possiblenationalaward is a tremendous matter. For getting recognition world-wide, one needs good critiques. Books too have to be printed on the subject,which are read overseas. to get international recognition. Here there is a void where famous critiques and curators are nonexistent.

“Kibria is one of the artists who has won ample accolades overseas," says Rafi Haque. "When it is said that the pioneer was a man of few words and that he had little social involvement, these factors – helped him work better. Just as he spoke little, he had a minimalist attitude in his work. This was one of his greatness. Secondly, he and Safiuddin came to Bengal, as artists, after 1947. As citizens they grew up in West Bengal. As citizens, in East Bengal, the then East Pakistan, their contact with society around them was little at the outset.

Kibria was lonely at the beginning. This element, limited friends and associates, this void was filled with his being immersed in his work. This involvement was so great, in case of the two artists, Kibria and Safiuddin, that no other artists of theirtime,could come up to their level. Their deep involvement was nonpareil.There was a great depth in theirwork, as a consequence. They became the ideal artists of their time – both inrealism or abstraction. Other artists vied with one another to get their opinion. To win some admiration from these two maestros was the greatest achievement for some of the artists.

“I will say that there is no artist to replace the two giants of our times. Perhapsthis emptiness within u us will stay forever.”

Kibria (second from left) with fellow artists and friends.

Khalid M. Mithu also has fond memories of the maestro.“I came to the ' Fine Arts Institute' in 1978. The following year, I did experimental work at home, and, showed them to Kibria, as told to doby Shahid Kabir. To show an artist or Kibria's stature my work which was not academic, required some courage on my part. Sir then came to my home to see my experimental work at my humble abode. This was a great achievement for me. The manner in which he embraced me was something unforgettable. Hetold me that what I was learning in my spare hours, the play of light and shade, was something I should always apply. What I feel today, aboutthis beloved, ideal artist, is that he will always be there in our minds toprotect us and lead us on.

“I feel that great artists of Kibria's stature, do their work and leave us: but the ruling authorioties do little to honour them in a befitting manner. For the future generations, it isvital that we preserve Kibria and his philosophy of life and art. The manner in which the National Museum operates, fifty years behind the modern times, will just not do. Qamrul Hasan and Kibria, should be well displayed before foreign eyes – to be admired and remembered for all times. This is the responsibility, I repeat of the ruling authorities. There should be seminars, slide shows, films and discussions of an artist of Kibria's stature. This is to create awareness in us, and this for not art buffs alone. I want the world to know that that this is our Kibria.”

Rafi Haque – a fast friend of Juneer, one of Kibria's sons – is an individual who has been close to Kibria in his last few days, says, “A few days earlier, abouta monthback, I had asked Kibria, 'What was the greatest ambition in your life'. He had replied, ' I wanted to be a school teacher– teaching how to create pictures.' Kibria had replied. He workedwithoutexpecting any great returns. He didn't have a single self-centred desire within him. He was not after any material satisfaction.

Monirul Islam, who has been in Bangladesh now for two years at least, having exhibitions and workshops, was staying near Kibria's house in the maestro's last few days. Monir, with his international fame and unsurpassed bonhomie says, "We often exchanged views and opinion about art – currant and future. National and international arena were discussed ad lib. For me he has not died and never will. His image, his paintings are timeless. His personality was overwhelming. Hispassing away is a huge loss for the world of art. Theimportance of his contribution, the school of Kibria – his textures and colour, his influence will always be there. There can never be a second Kibria," says Monir.

|

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |