|

Art

Portraits of Pride Portraits of Pride

Fayza Haq

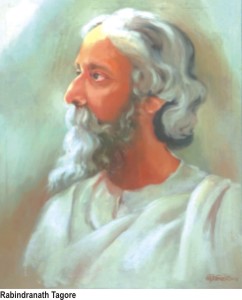

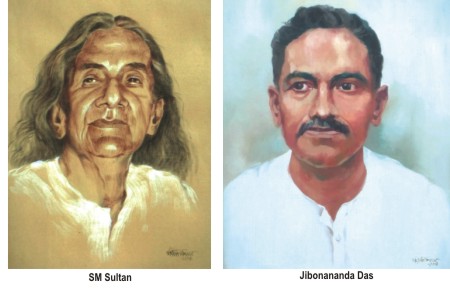

Portrait painting requires precision and perseverance. Kiriti Ranjan Biswas has about 40 large portraits of personalities who have contributed to Bangladeshi individuality and culture over the years. These are seen at " Shilpangan" in the exhibition entitled "Onupreronar Oboyob", which began on March 25th and runs till the 1st ofApril.

When he was about three, Kiriti copied portraits of characters like Nawab Shirazuddaula, done by his elder brother as doodles on brown paper covers of books. As he belonged to a Hindu family, Kiriti was familiar with figures of deities like Saraswati, and personalities from the Mahabharata, which he copied as a start of his career of portrait painting. In his school days he always carried a sketch- book in which he did portraits of people he liked. Working at an ad agency to make a living today, he has had to do a lot of figurative work, after he completed his Masters in Fine Arts in 1995 from India.

Asked which artists had influenced him most, Kiriti says he was inspired and motivated by Qayyum Chowdhury and SM Sultan. Michelangelo has been his favourite since he was a teenager, when he often visited churches to study the paintings on the walls. Among the portraits that Kiriti has done he feels that the portraits of those he admires immensely have turned out best such as that of SM Sultan, the film director Ritwik Ghattak, and writer and cultural activist Wahidul Haque. He enjoys doing work with the subject sitting for him, nor really caring too much about the financial gains from these paintings.

"As I'm linked with cultural activities such as that of 'Uddichi' my portraits capture faces of those who have excelled in the cultural field," says Kiriti. "I think that capturing the expression of the subject is vital." He aims at more than photographic representation. "The paintings should appear to be speaking to you," he says. In this exhibition he has tried to bring in those who've contributed most to our society here in Bangladesh, like Titumir and Surjya Sen, beginning with the time of rebellion against the British, two centuries back.

"My aim is to hold up for the new generation the personalities who have contributed most to our culture and Bangali origin. It is with difficulty that I managed to do the portrait of Surjo Sen, who originated from Bangladesh. Portraits of Titumir and Khudi Ram are rare and are often only basic sketches that go with 'puthis' and done by amateurs. I've been tracing them down for 12 years. Surjya Sen's assistant, Binod Bihari Chowdhury helped me get Surjya Sen's portrait after years of my research , here and in India.

Kiriti has also done portraits of the four national leaders Tajuddin Ahmed, Syed Nazrul, Qamruzzman, and Mansur Ali.

He paints at night, after his duty in his office, on holidays, and in between his allotted work at the office. He works on each portrait at a time, using oil and sometimes with poster colour with a dry brush. He enjoys oil the most as it is easier to manipulate.

Awe and Sorrow of the Padma

Monsur Ul Karim, winner of three prestigious awards including the "Ekushey Padak"-2009, talks about the changes in his work

Fayza Haq

|

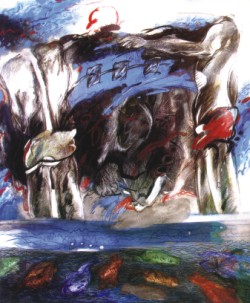

The Saga of the Padma-5, Acrylic on canvas, 99X92 cm, 2008. |

Born in 1950 in Rajbari, Mansr Ul Karim is one of Bangladesh's leading painters. The motif of his recent exhibition that is being held at Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts is the river Padma. It tells the tales of the once mighty river that has been an overpowering presence in the lives of the inhabitants of the Ganges delta. The river has been the muse of many an artist--Karim is the latest to depict the rhythm of life of the Padma, which from a distance now resembles a glittering silver ribbon carelessly dropped by a child.

Dwelling on the work seen in his ongoing exhibition at the Bengal Gallery, Mansur says, "There is a difference between the exhibit I had at Bengal Gallery in 2004 and this one. The reason is that I now dwell on what I call 'The Saga of the Padma'. I have dealt with the life around the Padma, the culture, the lifestyle, and the hardship of the people living around the riverbank. My own house is Rajbari, Faridpur, along the Padma, and I've spent a long time, my childhood and youth, studying the life of the people here.

"Earlier I did series such as 'Song of the field' and 'Source', which reflected uncomplicated rural life. All throughout I maintained the relationship between man and nature. Times have changed and this I tried to reflect in my work. There is less laughter and happiness as the river dries up. The aim is to depict the havoc and destruction of the times. Thus the work is less lyrical. My composition and thinking process is complex and contemporary."

In one of the paintings we see three semi-clad women who have come out for a bath along the river. This, incidentally, brings out the camaraderie that we find in the villages, where activities tend to be group orientated. This is in black and white, with touches of vermilion and tiny circles of green, to highlight the sensuous figure in centre. The figure on the right is sketched on lightly, while the third image has lashes of black.

Another painting holds out the pain and suffering of people, especially women and children, when the embankments of Padma break away. The feeling of insecurity, the desperate search for food and shelter is seen in the tortuous faces of the children and the hapless, care-worn partially clad mother-- wandering about the banks of the Padma to make ends meet. The bluish green used in the painting stands for sorrow.

Another work brings in two boats, which are sketched in, with the sails being clearly visible. The sky is a bright yellow, with two bits of clouds and the sun being a collection of dots. There is a lot of space. "I always try to leave a lot of white space for the viewer to make of what he will, and for the eye to rest," says Monsur.

|

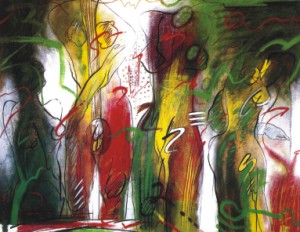

| The Saga of the Padma-31, Acrylic on canvas, 64X82 cm, 2008. |

Yet another painting presents a woman's torso in red. Bubbles depict the destroyed hopes of the people. This work remains sketchy and suggestive. "Lines, dots and forms are essential for a painting if one wants to depict abstract elements like hopes and desires. Colour alone cannot express these feelings. The colour is distributed all over the canvas. I have not tried to mix and merge the colours. If I've used red in one place, that alone dominates in that space. Despite the lack of blending, there is harmony in the composition on the canvas," the painter says.

In his present paintings the colour zones are clearly marked. His lines again, are bold , with textured space, in between. There are no elements of sentimentality, even though he depicts emotions and feelings.

Asked when he became seriously involved in painting, Monsur says," Before 1992 the works were individual art pieces. After that there was a mental change in me. From then on I wanted to focus on emotions and feelings and for this a series is requisite to drive home the point. In 1992 I recovered from a car accident and since then I feel my work has been more serious and complex."

Asked if he feels that artists are properly evaluated in Bangladesh, Monsur says," Although I respect the critics, I feel that critics do not always go into the unconscious mind of the artist. They do not always go into the depth of the working method of the painter. In 2004, in my exhibition at Bengal Gallery, I had left a lot of white space around the images of my work on the canvas. This was interpreted as a way of presenting an illustration, when, in fact, the work was a complete painting. The critic should try to speak with the artist and analyse his complete mentality. There would then be no room for miscomprehension."

Dwelling on his teachers who built the base for this painter nonpareil, Monsur says that it is the guidance and encouragement of Rashid Chowdhury and Rafiqun Nabi who brought him to the level of what he is now. "They taught me what was the essential quality of a good painting, and I'm grateful to them," says Monsur.

Talking about whether promotion of painting in Bangladesh tends to be Dhaka based Monsur says that most art dealing is done in Dhaka, no doubt. However, he says art coming from places like Chittagong and Rajshahi should also be considered. There are no good art galleries there, he says, and so no adequate patrons.

Asked about evaluation of the Bangladeshi art market-- whether it is good enough for an artist to make a living-- Monsur says that without contacts our artists are not given their true value. A few artists, it is seen, sell their paintings within days of the exhibit, while others, no matter how talented and persevering, fail to make a living without resorting to commercial art. Good work, without adequate publicity has failed even in the days of Van Gogh. "Today there's computer art. Architects and interior designers use the knowledge of fine art. Thus, of late, art-based work is expanding," says Monsur.

Does he believe in "Art for art's sake"? Monsur feels that art should have a social and economic reason behind it and should not just have decorative value.

Touching on his role during the Liberation War, Monsur says that all he could contribute, having fled to his home on the banks of the Padma, was to be an informer to our people, as he was busy sheltering his younger siblings, hiding from village to village.

Monsur's exhibition, which began on March 20, ends on March 31.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |