|

Tribute Tribute

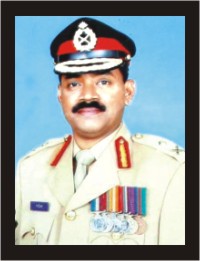

Shakil Ahmed

my scholar-soldier friend

Syed Badrul Ahsan

My friend Shakil Ahmed was a soldier who knew the myriad ways in which history worked. He read voraciously, spoke with eloquence and thought of the future of his country in a manner that marked him out as a scholar. But then, he had always been a scholar. When we met for the first time --- and that was at St. Francis Grammar School in Quetta, Pakistan, in 1970 --- we knew we would be good friends. I was in Junior Cambridge and he was in class nine. That made him, academically, a year junior to me. There was something about Bangali students in that overwhelmingly Pakistani school that singled them out for their brilliance. I was always ahead of everyone else in my class at every examination. There were others, younger than me, in similar conditions in other classes.

And then came the day when some of my classmates informed me that another Bangali had arrived and had beaten everyone else at his very first monthly examinations in class nine. My happiness and my curiosity led me into seeking this fellow Bangali out. It was tiffin recess when we met. That first meeting went off well and we certainly hit it off. For the next year or so, until I came home to occupied Bangladesh in mid 1971, Shakil and I regularly met in the school library. He had a passion for books, a quality that I was proud to share with him. Like me, he was a diminutive schoolboy. He borrowed serious works on history and literature from the library. So did I.

And then we lost touch. His family was stranded in Pakistan and would not return to Bangladesh until after liberation. When Shakil came back from Pakistan, we did not meet. There was a simple enough reason: neither of us knew where the other was. It would not be until early 1997 that we would link up once more, almost in the manner of a miracle. On a cold February day, I walked into the Bangladesh High Commission in London as the new minister (press); and Shakil was preparing to return to Dhaka after having served as assistant defence advisor there. When we met, we both tried to recollect where we had interacted with each other earlier. His face looked familiar to me and mine to him. Within seconds, we remembered the old grammar school days. It was a grand reunion.

|

| An army man is overcome by grief when entering the scene of the carnage. Photo: Shawkat Jamil |

In these nine years, since I came back home after my diplomatic stint in 2000, Shakil and I kept in regular touch. I made note of the way he was rising in the army; and he kept reading my articles and letting me know what he thought of my opinions. When he rose to the rank of a major general and then joined the Bangladesh Rifles as its chief, my happiness was indescribable. I called him, to tell him that it was my pride, my hubris if you will, to be his friend, to know that the Bangladesh army had in its midst a scholar-soldier of his stature. He laughed. He was too sophisticated, too humble to admit he was that. But he was. Three days before he was gunned down by a bunch of mutineers, Lieutenant General (retired) Hasan Mashhud Chowdhury and I spoke of Shakil Ahmed's intellectual brilliance. Whenever he needed a word or phrase in English, said the chairman of the Anti-Corruption Commission, he would consult Shakil, who served under Chowdhury when the latter was chief of army staff. And prompt and appropriate would be Shakil's response. There have been the many occasions when I would, on my way to work, join Shakil at his BDR office over coffee. We spoke of national politics, of geopolitics, of the so-called war on terror. And we dwelt at length on literature and history. Shakil Ahmed possessed an unambiguous comprehension of national politics. There was an intensity of patriotism in him. He never lost sight of the principles upon which the Bengali nation had gone to war against Pakistan in 1971. In his negotiations with senior officials of the Indian Border Security Force, he demonstrated skills that were evidence of the thorough homework he had done. In a society where not many have been able to create an impact while dealing with people from other countries, Shakil made a difference. Throughout the duration of the BDR's Operation Daal Bhaat programme, he managed things with finesse. Sometimes he joked that he had been reduced to being a shopkeeper. We both knew, though, that beyond the humour there were the ground realities the country was confronted with.

Shakil and I spoke when he called a few days before his murder. He wondered if we could meet and share thoughts on the direction Bangladesh could take now that democratic politics was back in place. I promised to call him back and arrange to meet. That meeting was not to be. On the morning the murderers struck, I tried contacting him on his cellular phone. The line was busy. I tried twice more. The line was still busy. Now I know he must have been trying desperately to get things back in order. When I tried calling him a fourth time, the phone went on ringing. He did not pick it up. He was probably dead by then.

Major General Shakil Ahmed, soldier par excellence, scholar past compare, lived honourably and died bravely. I salute the man of integrity he was. In the grey of twilight, I will think of his soul, carousing amidst the stars.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |

|