|

|

|

Chicken Eid

Cluck, cluck

I scratch patterns into the ground. My little chicken heart bristles with indignation, reducing me to venting my anger on the dust that lies thick on the ground. My singular rage seeks out something to hate. Beady-eyed glare, as I scan the vicinity for something I can pick on. My attention hones in on the ants that scuttle past my clawed feet. Ah, yes, the ants. I've found my new pet peeve. I scratch patterns into the ground. My little chicken heart bristles with indignation, reducing me to venting my anger on the dust that lies thick on the ground. My singular rage seeks out something to hate. Beady-eyed glare, as I scan the vicinity for something I can pick on. My attention hones in on the ants that scuttle past my clawed feet. Ah, yes, the ants. I've found my new pet peeve.

Or rather, I should say that the ants serve as my temporary new favourite pet peeve. I jab at the dust again, vehemently, poor ants flailing their limbs as they flee for safety. And in my malicious little heart they all have bovine faces. They chew their cud and moo balefully into the night, swiping the air with their tails. They steal the thunder. They steal my thunder. It depresses me.

Chicken feet leave constellations in the dust as somewhere over my head another cow moos balefully into the night. They've started to take over the street, thundering chunks of flesh and meat that smell only as cows can smell. They leave their offerings on the ground and reduce the neighbourhood kids to helpless giggling. 'Look at that one!' the children say, delight shining searchlights out of their eyes, and they point out one brown cow from the next. 'They all look the same, you know,' I want to tell them, but of course they don't care. Their attention, limited to begin with, sweeps right past me.

I feel absurdly left out. Standing on my two feet, feathered and winged, I am a veritable sore thumb in this sea of mooing. Had I lived in Roman times, I would be decked in Cassius' robes, demanding to know why those Caesars of cows towered over the rest of my kin. They're Colossuses, the lot of them, smugness radiating from every pore. From the bottom of my stringy little heart, I seethe at the attention that is lavished on them. The hay that arrives at regular intervals. The wide-eyed innocent five-year-old who teeters forward on his spindly legs to stroke a cow's head, holding in his hand a bough as somewhere in the darkness his father eggs him on. 'Go on, son, you know he's not going to bite.' When did a five-year-old ever try to feed me anything?

That's right. Never

It's because there's so many of us. Running around, flapping our under-appreciated wings, taking over the world one cheese omelette at a time. And not just omelettes, oh no, somewhere out there in some culinary school the next Iron Chef is coming up with some way to put chicken broth in broccoli ice cream. Yes, that's the deal. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner, after-dinner post-dessert, there's never a dearth of occasion for chicken. Want to know why? Versatility, baby. There's nothing chicken can't accomplish.

And yet, I don't see any day singled out for us. Oh, no, let's leave it to the cows, artery-clogging cud-chewing public property-littering beasts of burden, yes, the cows, they should get it all…

The chicken scratch that I started out with has now deepened into a veritable ditch. My frustration, I am surprised to find, runs as wide as a river in monsoon. Scratch, peck, attack the ants, it's an endless cycle. I scuttle past another wave of mooing monsters, as their proud owner parades them down the street. 'Oh, yes, got them for a steal!' he's mock-whispering, voice loud enough to carry past the Dhaka traffic. Men with thinly veiled contempt stop on the streets to eye the towering masses of flesh. 'Show-off,' someone mutters sotto voce, and I cluck my approval.

I keep pecking away, blunting my beak on the dust for as long as the jealousy writhes in the pit of my chicken guts. And when a cow trundles past me, swishing its tail in my face, I cluck obscenities in its general direction. 'Why don't you go back to where you came from?' I want to shout, but of course my voice is drowned. Already I can see the halos looming on their heads, their path to heaven already paved with gold. As it always is. Qurbanir Eid is just magnanimous like that.

By Shehtaz Huq

Book Review

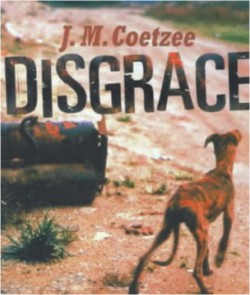

Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee

ERTAIN books become insubstantial. They disappear from the memory like nightmares dissipating in the light of the day. Others have a way of growing in stature, slowly, over time. And then there are the precious few which are forever engraved in your mind, as if carved out by lightning. Disgrace is one such book. ERTAIN books become insubstantial. They disappear from the memory like nightmares dissipating in the light of the day. Others have a way of growing in stature, slowly, over time. And then there are the precious few which are forever engraved in your mind, as if carved out by lightning. Disgrace is one such book.

Our protagonist is David Lurie, an aging white man living in post-apartheid South Africa. He teaches Communications and The Romantic Poets at a technical university in Cape Town. David is a man who is pleased with life; he has carved out a situation for himself in the world which he finds satisfactory. It is only when he converts his yearning for something more that the world strikes him down, brutally. And we feel that the world has not been entirely unjust. For David Lurie is not a pleasant protagonist. He is not, at heart, a good man. But neither is he a completely detestable one. He is immensely selfish and self-absorbed, using people to satisfy his needs and then throwing them away. In the opening chapters he feels lust for and then pursues one of his students. We feel that the girl allows the advances due to his relentless psychological pressure than any real attraction to him.

When the affair is discovered he is expelled from his post at the university. He decides to visit his daughter Lucy who is currently farming in the countryside. She is a tough, independent young woman who has her own life, away from her father. Even though he loves her we sense he is not satisfied with her life choices or with the people she surrounds herself with: not Bev Shaw who runs a pet clinic, not the cranky old farmer whose house is down the road, and especially not with Petrus, the black farm helper who has become an independent man. He holds himself aloof. He is cynical and sardonic. That is, until tragedy strikes.

An unsympathetic protagonist is difficult to write. One is never sure how to proceed, how much insight is important for the reader to have some level of connection with the protagonist to continue reading, but still recognize the unpleasantness of the character.

With David Lurie J.M. Coetzee proves himself capable of the undertaking. Using a deceptively simple but engaging semi-omniscient narration Coetzee slips us into the mind of Lurie. When David transgresses the narration seems cold and distant, to remind us to observe and judge him. When David is transgressed against the prose seems to seethe with righteous indignation. The way we view the story is intriguing as well. As David is our protagonist the world is seen filtered through his eyes. Everyone else seems stupid to us because that is how David perceives them. David's decisions, no matter how repulsive, seem to have a twisted logic to them, something not apparent in the other characters.

But that is not to say that the characters are one-dimensional. The last half of the book, in essence, is a character study of three individuals. Each stubborn, each independent, each determined to stick to their moral ideology. It is the story of what happens when three implacable forces meet at a crossroads in history. This is a book which raises questions. Hard ones. About the depth of human nature, about the brutal nature of man, about the racism that is passed down, almost genetically from parents to their children. Is David a racist? At times it seems blindingly obvious that he is. But consider, he probably never thought this way before. He probably voted against apartheid all his life, though he did little enough against it. And if circumstances can push one to extremes, how are we to know what lays hidden, dormant inside ourselves?

This book is truly a spectacular work of fiction. It succeeds as allegory, as historical fiction, as observant character study. Here is a book with convictions. It is a book that recognizes and asks questions that other books don't even know exist. Man's basic animalistic nature has been the subject, or underlying theme of many books. And this theme has seen a sudden resurgence this century. But few have managed to deal with the matter as incisively and as brilliantly as Mr. Coetzee. Let your latest Meg Cabot purchase slide in favour of this one. Anyone interested in literature will find this a necessity. Whether they will enjoy the experience is an entirely different matter. Winner of the 1999 Booker Prize

By Shoumik Hassin

The Light

Slowly I am walking towards the light,

Hoping in vain it would shine

Those colours are fading in the night

Yet I hope one of them is mine,

The light shining in its bright

Coloured glow that adorned this night.

And my dreams are running round

In circles, circling the light

From far I can hear its sound,

Coming to my ears, bordering those years

I have left behind, this tentative mind

Is telling me it should fade away,

The light can't light my face,

In this wilderness, all my days

A vacant hope still lit by its flame

That it would stay…

This night, this light.

By Sujash Islam

Yearning for a Drape of Gold

Running lines of mist shrouded the gold hued windows of her apartment

While dew drops raced reflecting shades of empty teal walls;

Her fingers scuffled through

her golden fabric

Up and down they scurried guided by restless rhythms of anxiety

Mirrored only in tiny droplets that clung on, waiting to be faded back to mist.

Saffron rays shuffled through the murkiness, furnishing an illusion of rising dust ingots

Yet all that kept her from bathing in its chilly warmth was a pane of opaque glass,

and a flushed skin that pined for

the touch of a loved.

Grasping tight her embroidered aanchal, creasing the carefully ironed

She traced the racing impatient droplets being dragged down from the windowpane

Fingering the cold bitter glass she traced each drop with her manicured fingernails

and when the hued droplets merged to form translucent drops, her lips smiled to realize

Wrapped in adorned embellishments she remained a princess of only modern parodies.

By Adnan MS Fakir |

|