| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 45| November 16, 2012 | |

|

|

Perspective

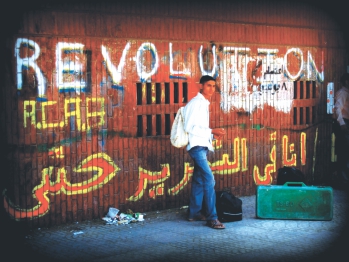

YEAR I OF THE "ARAB REVOLUTIONS" The Dhaka and Chittagong Alliances Françaises are holding a series of Arab-Spring related events this November, including a conference debate at Dhaka University on November 20th, bringing together French and Bangladeshi intellectuals and academics. This is one of the texts written by a leading French expert in the run up to the event. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Benjamin Stora How to make sense of the Arab revolutions more than one year after their outbreak? The accession to power of Islamic parties in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya or Morocco came as such a shock that one may wonder what the ultimate meaning of these revolutions is. Has one gone from “spring” to “winter”, to take up the phrase used by a number of analysts? Tunisia inaugurated what has come to be known as the “Arab Spring”. A year later, its former President, Ben Ali, belongs in the dustbin of history. History has accelerated and the country now faces a serious social crisis and major democratic challenges. Many regions are affected by high unemployment rates: 19 percent is the national average rate but in some inland areas that had been left out for decades, it reaches up to 50 percent. A series of recent attempted self-immolations, over a hundred in one year, go to show how desperate some sections the population are (in Tunisia such acts have a strong symbolic impact as the whole revolution started off with someone setting himself on fire). Another risk factor for Tunisia is the lack of democratic experience. The leaders of the former ruling party have migrated to other parties, casting serious doubt on the validity of the democratic process. In the country's broader context, the victory of the Islamic party “Ennahdha” has given free rein to the forces of obscurantism and ignorance. So is the Tunisian revolution a revolution for nothing, a revolution pointing towards a regression? Many Tunisians are adamant that it will be difficult to deprive them of their newly and dearly acquired freedom of expression. In the wake of the Tunisian revolution, other large scale events have taken place in other parts of the Arab world, in Egypt, in Libya, in Syria… Are these to be understood as regressions (what with the accompanying social crises and the advent of religious obscurantism) or as a process of liberation and empowerment? Which way is all this going? The Arab world is at a crucial crossroads in its history, involving the emergence of societies yearning for equality and freedom. There is no need to remain silent, suffering, accept or trick reality anymore. Fear has vanished. People can at last express themselves straightforwardly and speak their minds, not only to their most reliable friends in the private sphere, the only place where they could possibly voice their opinions on the powers that be, the shortcomings of the state or economic problems. Such debates used to be virtually excluded from the public arena. “Al Jazeera” is no longer the one and only TV channel that invites opponents of the regime or intellectuals to participate in bona fide talk shows. In Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, newspapers no longer try to hide reality or bypass it as they used to (and as they still do in Syria). Diversity and plurality of opinions are the order of the day.

A distinct feature of these movements is that they do not hinge on one single leader. Likewise, with their slogan “Clear off!” the demonstrators have managed to oust authoritarian leaders. Since they gained independence, most Arab countries had been ruled by extremely centralised and personalised regimes. State-building had been given priority over the rights of citizens. Today's revolts challenge the authoritarian centralisation and concentration of powers in the hands of a few. That is why, in most countries, the demonstrators took it out on the state apparatus or the head of state. There was no intention of destroying the state as such, rather of ensuring better redistribution of its functions and powers. Another demand was the end of the culture of secrecy shrouding the running of these centralized governments. Arab societies take it for granted that politics takes place “behind the curtain”, backstage, in a total lack of openness. Nowadays citizens want to do away with this culture of secrecy and aspire to live in a more open society. How would it possibly be otherwise with the Internet anyway? Arab societies are now ripe for the emergence of real political parties, not parties led by a few. Likewise, they are in need of real unions leaders or of intellectuals who are critical and do not necessarily flatter the powers that be. Protest, criticism and new behaviour patterns all testify to the emergence of a process of individualisation. Take for instance the “harragas”, these North African youngsters who will go to any length to leave their country. They will unfailingly declare that they do not leave their country as “ambassadors”, on behalf of their families, their neighbourhoods or their villages as was the case in the past. They are leaving on their own behalf. There are other indications. In his book Générations arabes (Arab Generations) (2000), researcher Philipe Fargues described the demographic factors that explain today's evolution (especially the impact of smaller family units). The modernisation of society appeared to be the cause as well as the consequence of demographic downfall affecting the Muslim world in North Africa and the Middle-East, from Rabat to Tehran, with the possible exception of the Gaza Strip, with its legacy of continuous conflict. This trend was probably linked to a fear of the future: when people do not know what the future has in store for them, they usually have fewer children. This is all the more relevant as the decline of Messianic ideologies such as nationalism or Islamism prevented them assuming the role they traditionally play in helping people not to fear the unknown. In addition to the issue of the “harragas” and to demographics, another indication had been the ever-rising levels of electoral abstention (although never officially acknowledged) as well as the permanent brain drain. For a few years the Arab world had seen the advent of the individual, i.e. of a person who can exist regardless of the state, of their family or their community. Even religious practice can nowadays be seen as expressing of a personal, individual belief and not solely as respect for communal tradition. Religious belief is not imposed by family tradition, it reflects personal conviction. Yet another major change lies in the fact that politics have taken to the streets, not only for social protests as had been the case for a number of years. These protests are of a political nature. Simultaneously and as a concomitant, citizenship is emerging. These civil societies express the desire to uphold their rights in the face of the state, be it a monarchy or a republic. As a result, the old political forces are being challenged and have no choice but to get reorganised. These revolutionary (or at least anti-establishment) movements call for a complete overhaul of the traditional political systems of the Arab world. The old cliques, dating back to the heydays of nationalism, run the risk of being sidelined or becoming ineffective.

All these protest movements intensify the crisis of Arab nationalism, the ideology that presided over the creation of one-party systems. They will also force political Islam to redefine itself. The Islamists who have risen to power have no prior experience in state affairs and they will have to compromise with new societies. The Islamists have won free and fair elections. Yet the situation varies greatly in Tunisia, Egypt and Morocco as political Islam has a different history in each of these countries, which need to be closely watched individually. Movements whose founding principles are theocratic in essence and whose aim is to homogenise society do justifiably inspire fear and dread. Indeed, a society is homogenised along the lines of a one-nation concept, of a dominant ideology or belief, leaves no room for plurality and dissidence. But for the time being, the Islamists cannot claim to represent the whole nation or embody the “whole people's party”. In societies that are undergoing such a process of individualisation such claim is just not possible. In the opposite camp, the democratic blocs may be divided but they are nonetheless very much present. Also, the host of media, political parties and associations that have emerged during the revolutions testifies to the vitality of their democratic potential. In a society that is no longer dominated by fear, individual men and women will take control of their destinies, thus making it difficult to revert to the status quo ante (unless it is restored by a bloody war). The courage shown by the Syrians today is proof that even if repression is fierce, nothing will ever be the same in the Arab world. It will be more difficult for the states, with their castes, their bureaucrats and their oligarchs, to make decisions without taking people into consideration. That is why it can be said that a threshold has been crossed, even if the changes seem too few and far between, too easily suppressed or checked, or else appear to be quite worrying, as in the case of the Islamists' rise to power. What is happening is a sea change redefining both the relationships between people and society and the national bonds. Since the end of the colonial era, a simple vision of the State and Nation had prevailed: the State protected and defined the boundaries of the Nation. Attacking the State (seen as the protector of the Nation) meant dividing the Nation and endangering its very existence. Today it is not only the State that protects the Nation, but the advent of civil society that consolidates the Nation. There may be a risk that politics become confined to the religious sphere (in Egypt, the Muslim Brothers and the Salafists seem intent on fighting it out), yet it is essential to help (and take stock of) the democratic forces in the making. It is essential to get involved in the battle that is just starting, a battle that involves issues the Arab world has long shunned - the status of women and of non-Muslim minorities, the secularization of the state and the new relations with the Western world. A new, arduous, and very specific chapter in history has opened. Benjamin Stora is professor of Maghreb History at the Institute of Oriental Civilizations and Languages (INALCO) in Paris and University Paris 13 - Villetaneuse. He is France's leading expert on the history of Algeria.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |