| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 26| June 29, 2012 | |

|

|

Theatre The Search for Peace Parnab Mukherjee attempts to portray South Asia's present-day reality in light of Mahatma Gandhi's journey to the conflicting regions of the sub-continent Tamanna Khan

When the embers of religious and ethnic hatred burned the Indian subcontinent into ashes, a leader responded by not signing orders for the use of rubber bullets, hot water tanks or batons or by not projecting garrulous orations at organised meetings. He simply walked through the burning villages, talked to the victims and the perpetrators, explaining to them the need for a homogenous society. Through his fasts he tried to teach the unruly lot the virtue of tolerance of the other. Unfortunately, the man who practiced and preached non-violence met a violent end from his very countrymen, who listened to him, idolised him and then left him in the museum to be revered from a distance. That today is the reality of Mahatma Gandhi and his South Asia and Parnab Mukherjee, an Indian journalist and curator, artistically presents the reality to a Bangladeshi audience through his curated installation voyage and a performance project, ‘Talking Gandhi: Noakhali to Nowhere’. The exhibition which ends on June 29, starts from the outer wall of the Britto Arts Trust gallery, which is adorned with simple cotton attires symbolically representing Gandhi's Satyagraha or non-violent resistance. A map of the train route that took Gandhi across Bengal, welcomes the audience to begin their exploration of Gandhian teachings. Before entering the gallery Parnab explains how he tried to retrace Gandhian response to the places of conflict that Gandhi visited, both in terms of Gandhi's presence, what he said and what he would have liked to say. In the curator's note Parnab explains the reasons for choosing Gandhi's visit to Noakhali, a remote district of Bangladesh. He starts with a reference to a letter written by Phillip Talbot, South Asia correspondent of the Chicago Daily, who travelled to Noakhali to be with Gandhi. In the letter, Talbot presented the situation that persisted in the region in 1947 and the implication of Gandhi's tour to East Bengal. Parnab picks up where Gandhi left – the present day South Asian nations, where human rights violations, suppression by state and religious intolerance still prevail. Parnab has tried to portray Gandhi's thoughts during his five-month stay in Noakhali, where he trekked through 230 locations of the district. “There is a list of places, maps with the brochure which somebody can use if they go to Noakhali,” Parnab informs, also mentioning the rail route that had taken the Mahatma across the greater Bengal from Kolkata to Tripura. He sarcastically adds how, after the partition, one has to fly from Kolkata to Tripura. Sarcasm in fact prevails all throughout Parnab's performance as he uses it to poke at our benumbed conscience.

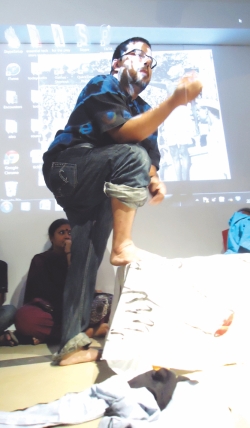

Inside the gallery, five zones with exhibits of photographs and sketches of Gandhi, give a feel of the great man's tour. The first block presents photographs of Gandhi in Noakhali at that time and a few photographs of present day Noakhali. In one block, Parnab presents some works of KM Adimoolam, a South Indian artiste who has produced about 100 drawings of Gandhi, depicting 60 years of his life. Another block pays homage to Umashankar Joshi, a Gujarati poet and writer who published a number of children's books on Gandhi. Parnab also pays tribute to Kosturba Gandhi's hardship by including the photograph of the Aga Khan's palace where Kosturba died. He says, “Gandhiji did probably many hunger strikes in his life but the person who fell to the hunger strikes or the medical implications after that was his wife.” The fifth block is a photographic presentation of Bihar in 1947, another epicentre of violence. Here Parnab introduces Jagan Mehta, a forgotten photographer, “who unfortunately amongst the first to chronicle the sub-continent in black-and-white photography and is neither documented nor remembered," he says. A self-taught photographer, Jagan Mehta joined the independence movement to document Gandhi's life in posterity. In early 1947, he was able to capture Gandhi in his last peace march to Bihar. The exhibition also includes video clips of the Birla House at Delhi where Gandhi was shot and documentaries on Irom Sharmila Chanu, the Iron Lady from Manipur, India. Irom Sharmila has been following Gandhian principle of non-violent protest against India's Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 by fasting since 2000. This act which gives unprecedented power to Indian military to take arbitrary action at will without any legal or judicial accountability is used to curb insurgency. However, like any other draconian law, AFPSA has rather become a tool for violating human rights. In fact, such state endorsed violence and submission to the boots become Parnab's main focus in his 45-minute-long solo performance, which he carries out within the gallery's space. In fact, the audience becomes a part of his performance as he moves through them or throws objects at them. “As a theatre director I work with alternative spaces which can be a closed jute mill or a coal mine or a stage,” he explains, seeking to capture the essence of the space that exists between the auditorium and street-theatre. Parnab thus deliberately breaks the line between the performer and the audience. Even his disorganised ways of switching on the projector to screen the video clippings in between his monologues becomes a part of the act.

However, it is not Parnab's body language or facial expression that captivates the audience. His witty dialogues, the force of his voice and projection bring in the different characters he plays. He presents himself as a person under interrogation who is asked about his profession, a conventional identity for a human being in our society. Parnab proceeds to describe his professions – throwing pebbles at closed windows or leaving empty postcards to people's houses to write to each other which become metaphorical symbols of openness, tolerance and freedom of speech. In a way, they reflect Gandhi's philosophy. In between his performance, the audience is introduced to a Kashmiri cartoonist who faced military interrogation because of his ethnic and religious identity; an interview of Mahesweta Devi is screened, where she relates her experience of knowing Gandhi; a list of people subjected to enforced disappearance in Manipur also appears. Parnab shows his disgust at every form of injustice in a unique way. It is not a smoothly written well rehearsed act. Spontaneity and improvisation marks the performance. It provokes thoughts and raises questions. The violence, the enforcement of AFPSA does not remain foreign as one watches the list of victims of enforced disappearance or the dead bodies of young Indian boys being carried away by Indian soldiers. According to Parnab, Gandhi was able to foresee this organised violence that throngs South Asia even today. “Gandhi had reached these organised spots of conflict far ahead of their occurrence. He could see the conflict, understand it and negotiate it,” he says. 'Talking Gandhi: Noakhali to Nowhere' tries not only to portray state violence but also our inner violence in conforming to norms or in the mistrust of the other. Instead of taking lessons from Gandhi's experience of Noakhali, the people of South Asia are wandering nowhere in search of peaceful solutions to their conflicts.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |