| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 12| March 23, 2012 | |

|

|

Cover Story History of the Masses Liberation War Museum's endeavour to collect eye-witnesses' accounts of the Liberation War of 1971, through the representatives of the new generation, provides new dimension to the history of our nation. Tamanna Khan

In 2010, Lamisa Rehnuma, a student of class six of YWCA Higher Secondary Girl's School, came to visit the Liberation War Museum (LWM) at Segun Bagicha Dhaka on a study tour. The tour was sponsored by the museum as part of its outreach programme. After the tour, when they gathered on the open premises of the museum to take part in a quiz competition on 1971, the museum staff made an unusual request to all the students. “They told us to find stories about the war from people close to us who had experienced the war and then writing them down for the museum,” recalls Rehuma, “I had heard stories of the war from my grandfather. His brother's son had gone out on the night of March 25 (1971) and never returned. Later his dead body was found in a nearby creek.” After a week or two, Rehnuma wrote down the incident and submitted it to a teacher at her school. She proudly informs that a year later, she was invited to a programme of the Liberation War Museum to read out the account she had written down from her grandfather's narration. Like Rehnuma, thousands of students all across Bangladesh have been beckoned by the Liberation War Museum, through its outreach programme which started in 2004. The LWM, established in 1996, launched the programme offering students of different educational institutions within Dhaka a one-day tour of the museum. Students of schools, colleges and madrasas, located outside Dhaka, get an opportunity to visit LWM's mobile museum, a bus that carries some of the exhibits of the museum across the country.

Initially the aim of the programme was only to bring to the students — the new generation of Bangladesh—the history of freedom of the nation. Soon, the trustees began to see another possibility of this programme. Sitting at the small kiosk of the museum, Mofidul Haque, one of the trustees of the LWM, says, “The war of 1971 had taken place throughout the country. Almost every family had to suffer, bear the burden of torture or had played some role in the war. Besides, in many cases a family member or two were involved in the war. So we felt if we could grasp that picture through them (the students),” Haque continues, “Then it would be a huge task.” Thus began the Liberation War Museum's Oral History project. “Oral history is a part of history. Oral history is not history,” Haque emphasises. He says that the real voice of people comes up through oral history. “It is said that there is no model for oral history. Every oral history is unique,” he adds. While comparing the oral history project of the LWM with that of other countries, Haque claims the LWM's to be the largest one which is being collected almost without any cost. Till date about 18000 eye-witnesses' accounts have been collected through the students of different educational institutions all over Bangladesh. While students of Dhaka who are brought to the museum are informed of the project, the collection outside Dhaka requires a little more work. Satyajit Roy Majumder, Manager-Development Education and Publication, LWM, says, “First we carry out a survey. We select a district, where the mobile museum will travel,” he says. He continues to describe how Ranajit Kumar, the project coordinator with the help of another colleague tries often to contact the educational institutions in each and every upazilla, where the mobile museum can travel. “It is not possible to cover all the schools and colleges. At best we can visit two-three educational institutes in an upazilla. After making contacts, we prepare a schedule of when and where we shall visit,” Majumder says. In its endeavour to reach out to the educational institutions outside Dhaka, the LWM has, till date, has covered about 40 districts out of 64.

A five-member team of the Liberation War Museum stays in a district for a month. At the educational institutes they exhibit relics, screen a documentary on the Liberation War and display posters on human rights issues. “During the programme we ask students to go to an elderly eye-witness of the Liberation War. The eye-witness can be anyone. A person within the family or not, a freedom fighter or not —he or she may be a shopkeeper, a pedestrian, lawyer, doctor, mother, father, uncle, aunty— anyone,” Majumder stresses. The students are asked to listen to the accounts of the person who was in Bangladesh during the war and witnessed it. “After listening to the experience, he or she will write down the narrator's name, address and identity, as well as his or her own and write down that history,” explains Majumder. To keep the task simple, LWM does not give out any instructions or samples to follow for recording the narration. Rather students are told not to worry about spelling and grammatical errors. Interested students submit their collection of memories voluntarily to a network teacher at each educational institution. A network teacher is selected by the institution to take the responsibility of collecting and sending the writings to LWM. Through the network teacher the Liberation War Museum keeps in touch with the institution and the students.

“After receiving the write-ups, we compose and make minor corrections,” Majumder describes. However, Haque informs that other then correction of gross mistakes such as important dates like March 26, December 16 and so on, the editing is kept to a minimum. “We even keep the language style to maintain originality,” Haque adds. The Liberation War Museum, however, does not carry out individual verification of these accounts. “In one or two percent of the cases, the students did not get the proper message and had sent write ups copied from text or story books,” he says. Haque adds that, proving their initial fear wrong, most of the accounts do not also include too much of general historical facts probably because of the intimacy between the narrator and the collector.

The authenticity of the narration will be judged when an independent researcher starts working with these accounts as resource materials. Moreover, the accounts from a particular area often refer to the same event from different perspectives from which the truth can be extracted. Since the students submit the write-ups individually, they do not know what his or her classmate has written. This process itself provides authenticity to some extent. Through this programme not only the untold stories of the war are being documented but the new generation are acting as the messengers of the unwritten history. Mofidul Haque explains the implications of these accounts and the process through which it is collected. “There are a number of dimensions to it. One is its educational aspect. A student is conducting an independent interview,” he says, noting that the student is listening to a unique experience separate from what is written in the book. They carry out this task without any expectation of a good result or prize, he adds.

However, the Liberation War Museum does send a letter of recognition addressed to the student for each account they receive. “May be s/he never received a letter in his or her name before,” comments Haque, highlighting the importance of the letter of recognition. “We tell them that we will collect each of the writings properly in our 'Archives of Memory' by encapsulating it, the way a paper document is preserved. We are saying this not only to provide recognition to the student but also considering the value of the experience of the person, which has been documented here.”

In most cases the accounts have been collected from elderly family members as a result it creates a bridge between two generations. Besides the emotional value, these accounts are making significant contribution to history. “If we receive 100 writings from an area, those writings somehow or the other reflect the local history of that area,” Haque says. This specially happens when a village school sends the writings of its student. Usually the museum, sends back the composed copies of the accounts, to the educational institutions. Haque points out that the spiral-bound copies of the account sent to the educational institutions are kept in libraries and can be used as research materials. “Another aspect of our oral history is its reflection of a personal encounter between the young interviewer and the person being interviewed. Usually in collecting oral history some historians are trained. They carry recorders. They record it (the accounts), transcribe it and then prepare the material for oral history. In our case, there is no recorder. The account is being written through an intimate conversation,” Haque explains. In formal oral history, he opines, that warmth and intimacy is absent.

The eye-witnesses’ accounts in the boxes have been extracted and translated from the booklets of Liberation War Museum by ANIKA HOSSAIN. Tarpor Ar Khalake Khuje Paoa Jaini My mother had two brothers and a sister. She was three years old during the Liberation War, her brothers were 15 and 12 and her sister was 19 years old. On that fateful and horrifying night, my mother and her family were asleep as usual, when the sounds of gunshots woke them up. They tried to escape but they could not. They were immediately captured by the Pakistani army. They grabbed my eldest uncle by the throat and asked him to say “Pakistan Zindabad.” My uncle refused and instead shouted “Bangladesh Zindabad!” Hearing this, they shot and killed him. My grandmother screamed in horror and anguish. It was of no use. The Pakistani dogs screamed at her to shut up. It was then that they noticed my aunt. They asked my grandfather if she was his daughter and he said yes. They moved toward her and started to take her sari off. Unable to bear this sight my grandfather protested saying “Let go of her, you dogs! This country will be free soon and you won't be able to carry on this torture for long!” The Pakistani animals were angered by this and shot my grandfather as well. They then took my aunt and went on their way. Her family never found her again. My grandmother was not able to get her husband and son buried. She and her two children survived, but while they were trying to escape, a bomb blast crippled my grandmother's leg. She says that that day will haunt her forever. Written by: Faisal Arefin (Nayan), 6th grade, Ramdiya Bikrambishi High School. Gamchati Buke Jorie Ajo Tini Kaden August 1971. The Pakistani hyenas attacked Borobongram Market at Pangsha. They burned the stores and shot and killed a number of people. The news had spread all over the village. Mokim pagol (madman) had just sat down to have some rice. When he heard the news he abandoned his meal, wrapped gamcha (scarf) around his neck and set off toward the market place. What a sight it was! The villagers fleeing and the sight of the military and Mokim headed right towards them. Mokim might have been crazy but he was still a human being, not an animal like the Pakistanis. He could not bear to watch silently as the poor people of the village lost their shops and their hard earned livelihood for no reason. He picked up a kolosh (water pot) and collected water from a nearby river (Shirajpur's haur) and went to put out the fire. The military kept shoving him aside but Mokim was determined. He abused the military using the foulest language he knew. “Rascals! Do these stores belong to your forefathers? What makes you think you can burn them just like that? You think we didn't work hard to build them with our own hands?” Mokim refused to listen to the military. At one point, the military grabbed him and dragged him to the riverside. The lay him down and sliced his throat with a knife, as though he was nothing more than a sacrificial lamb. Then they chopped his body into pieces and threw them into the water. Mokim's mother Marium heard what was happening from the villagers and ran towards the riverside. All she found was fire everywhere, bloodied boot marks on the ground, torn up dead bodies, and Mokim's gamcha, lying on the river bank, next to blood red, still water. After searching for a long time, all they found was Mokim's skull, without his eyes in their sockets. At the sight of his mangled head, Mokim's mother lost her eyesight. She still carries his gamcha around wherever she goes, tears flowing never endingly from her sightless eyes. Written by: Najmun Nahar Mishu, 10th grade, Pangsha George Pilot High School. Shikha Shater A well known man named Fakir Chairman had a son, who was a student at Dhaka University. During the Liberation War, 17 of his son's friends came to his house with the intention to join the Muktibahini (freedom fighters). The son did not know that his father was a razakar (collaborator). One day, when the son was not home, his father turned the 17 friends over to the Pakistani army, who dug a large unmarked grave and buried them alive. The son never knew of his father's treachery or the fate of his friends. Those who knew what had happened were afraid of Fakir Chairman, who was an influential man, so they kept silent and stayed away. Today, a memorial stands at this grave site, honouring the 17 brave young students, who gave their lives for the country. This memorial is named Shika Shater and is located in Lalpur. Written by: Pabel Ahmed, 9th grade, Chatak Bahumukhi High School. Nij Hatey Shishutike Tara Ekti Dobar Niche Rakhlo Before she started to talk, grandma became somewhat distracted. Then she started saying, “There was a Pakistani camp near our house. So everyone moved to a safe place. Alas! Where was it safe? The Pakistani wild animals were feasting on Bangladesh a thousand times.” One day my grandma left her two-year-old daughter in a wood to collect some food and water from another house. Suddenly, she heard bullets fired in that house. What a cruel turn of fate! My grandma could not escape the eyes of the cruel Pakistanis. Pakistanis fired and a bullet hit her left hand tearing her elbow apart. By the grace of the Almighty she survived. But the sad thing was, where would she get medical help? Somehow with first aid she continued to live. It is difficult to rear a small child during a war. Besides, it is difficult to carry a child with one hand. It is very painful. After a few days, again there was the sound of bullets. Suddenly, the Pakistanis came in hot pursuit. My grandma started running away with the child in one hand. At one point, the child fell off from her hand, but there was no opportunity to pick her up. The military in pursuit noticed the child’s hand and trampled her to a bloody death with their boots. Later at night, grandma returned at that place and started looking for the child. Having found, not an alive but the dead blood covered body of the child, she lost consciousness. Later, grandfather rescued her from there and kept the child's body in a stagnant water body. Relating this much, my grandma started howling and said, “You have ignited fire on my body by reminding me of those sad memories. You have rekindled my pain.” Written by: Nurjahan, Class-ten, Rajarhaat Pilot High-School, Rajarhaat, Kurigram. They Call Me Freedom Just like a Wavin' Flag Sushmita S Preetha The Liberation War of 1971 was fought on many fronts. While some used guns and bayonets to fight the Pakistani army, others wrote passionate essays and fiction portraying the atrocities of the occupation; while some travelled all over the country, singing songs of freedom to motivate the people, others nursed the wounded. However, 31 people participated in the war in one of the most unexpected ways possible. Instead of taking up arms against the Pakistani army, they took up football. Curling free kicks and remarkable passes replaced guns and bombs as they fought their battles in football fields across India.

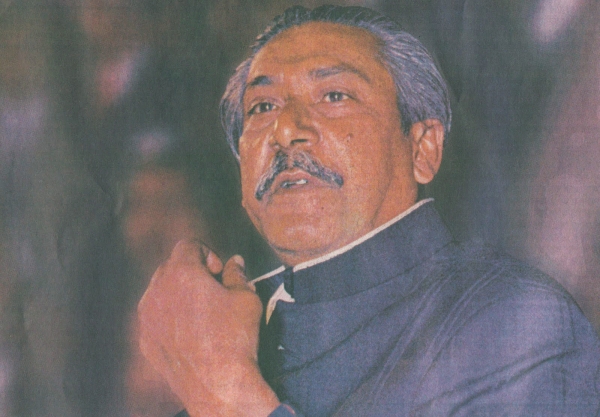

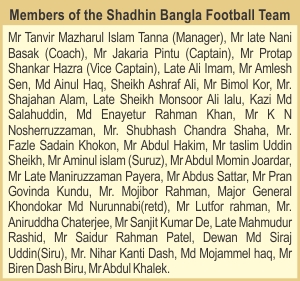

The Shadhin Bangla Football Team was formed in 1971 to collect money for the Muktijuddho Fund and to raise awareness about the war. “We played 16 matches in India, and collected Tk. 5 lakh,” says Jakaria Pintu, captain of the Shadhin Bangla Football Team. “When we made our donation, the fund's balance was nil. We have heard that our money was used to buy arms for the freedom fighters for the first time. That is definitely one of our achievements.” Before he joined the team, Jakaria Pintu was a fitness instructor at a camp in Balurghat sector, providing physical training to freedom fighters before they were sent off for further training. “When Bangabandhu asked us to join the war with whatever we had in his speech on March 7, I thought to myself, I have nothing but football to offer,” recalls Pintu. He crossed the border thinking he could play in India in order to raise funds, but once the war started, he became an instructor at a reception camp near the border. “I was prepared to join the war, but then my wife told me to form a team and contribute in the best way I could. So I went to Kolkata, where I found that some players were already thinking about forming such a team,” he adds. In Kolkata, Pintu met talented and resourceful footballers like Nani Bashak, Ali Imam and Pratap Shankar Hazra. Hazra, who later became the vice-captain of Shadhin Bangla, reminiscences about his experiences in 1971: “The Pakistani army burnt down our house in March 26. We escaped and took refuge in our friends' house before finally going to Kolkata.” There, Hazra came across Ali Imam who told him that he wanted to form a football team with the help of the Indian Football Association (IFA), and asked him to join.

After a few days, they received news that the Bangladesh Government (Mujibnagar government in exile) wanted to create a team of its own. “They asked us if we wanted to help. We were very happy to hear the news, since we were already in the process of forming a team,” asserts Hazra. The informal group met with Shamsul Haque, an MP during that time, and a few other prominent personalities, and officially formed the Shadhin Bangla Football Team. Then they began to regularly broadcast announcements on Akashbani (Kolkata radio), urging players who were near the border to come and join the team. Around forty players showed up, from which twenty-five/twenty-six were selected after try-outs. A few other well-known names were later added to the list as players travelled from Dhaka to join the team. Kazi Salahuddin, the current president of the Bangladesh Football Federation, played under the pseudonym 'Turjo Hazra' borrowing Prantap Shankar Hazra's surname to ensure the safety of his family in the then East Pakistan. The first match of the Shadhin Bangla Football Team against Nadia Ekadosh was a historic event. “It was the first time that the flag of Bangladesh was hoisted on foreign soil,” remembers Pintu with pride. Around fifteen thousand people attended the match. “At first, the authorities didn't allow us to let us hoist our flag, but we refused play otherwise. After all, if they could fly their national flag, why couldn't we fly ours? After half an hour or so, when the crowd became restless and rowdy, the then DC let us raise our flag, even though legally the Indian government couldn't acknowledge the existence of Bangladesh. We sang 'Amar Shonar Bangla' and then paraded the field with our flag and heads held high,” reminiscences Hazra. The then DC, DK Ghosh, was suspended for allowing Shadhin Bangla to hoist the Bangladeshi flag. The second match was played against the famous West Bengal team, Mohonbagan, which had to play under a different name for fear that it would be suspended by the IFA. The IFA, meanwhile, was under pressure from FIFA. The Indian teams and the IFA had to bend a few rules in order to allow the team to represent the yet to be free Bangladesh.

Apart from collecting money for the Muktijuddho Fund, one of the main objectives of the football matches was to increase the awareness of Indians, especially Indian Muslims, about the Liberation War. “Many Muslims there believed that the war was being instigated by Hindus in East Pakistan; they couldn't accept that Bengali Muslims wanted to be free from West Pakistan,” says Hazra. He remembers a match that the team played in a Muslim populated area, when people gathered around them and asked them to recite ayats from the Quran to prove that they were Muslims. They soon realised that of the 22 players, only 4 were Hindus and the overwhelming majority were Muslims. “Before that they were against us, and wanted to stop the match, but once they realised that Muslims were also involved in the war, the spectators began to cheer for us and support us,” recalls Hazra. The players also remember the last match they played in Bombay, organised by the Bharat-Bangladesh Maitry Samity, where celebrities like Sharmila Tagore and SD Burman came to show their support. The then cricket captain of India, Nawab Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, played in the football match and even scored a goal. The Nawab donated Tk. 20,000 to the Muktijoddho Fund, which, at that time, was a considerable amount.

The footballers are proud and grateful for the opportunity to have been a part of the Shadhin Bangla Football Team and this country's history. “Brazil, Argentina, Spain might be world champions now, but we are the first country in the world which had a freedom fighter's football team,” declares Pintu. “People supported us everywhere we played, which we are very grateful for. We were the first football team to hoist our own flag in foreign soil.” Pintu, however, urges the present government to honour the contribution of people like DK Ghosh (the DC who was suspended), Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, Bangladesh-India Maitry Samity's Shishir Ghosh, who helped organise the matches, and Topon Chatterjee, a photojournalist, who travelled with the team and captured their photos. The footballers consider themselves to be freedom fighters. As Amlesh Sen, the current manager of Abahani and team member of Shadhin Bangla, says, “Our names have been included in the Freedom Fighter's Gazette. We were already in camps, preparing for the war, when the High Commission urged us to come and join the team. Thirty of us were selected, and the rest went back to fighting in the war. We joined the team on the country's appeal, so I feel proud to be a part of it.” The thirty footballers of the Shadhin Bangla Football Team might have gone on to play for different leagues and the national team itself, and made names for themselves as talented footballers, but it was their contribution during the war that makes them stand out in the pages of history. As Jakaria Pintu so rightfully says, “Teams will come and teams will go, but there won't ever be a team like ours.” Neglecting the Wounded The state of the temporary Juddhahoto Muktijoddha Bisramagar (Home for Wounded War Veterans) in Tejgaon Commercial Area makes us reflect on what we are giving in return to those who won us our freedom Sharmin Ahmed

When one walks through the rusty white gates of Bangladesh Muktijoddha Kalyan Trust office in Tejgaon commercial area, one is met with a huge pile of empty soft drink bottles - the place once belonged to the Coca Cola Company. The thickness of the dust accumulated on the heap, indicates that they have been there for a very long time. The old building with paint peeling off the walls beside the debris has a sign board saying Roshni Printing Press. This is where the Juddhahoto Muktijoddha Bisramagar has been temporarily located. The Bisramagar established in 1972 at Mohammadpur College Gate, by the Trust for freedom-fighters in need of medical assistance. It was shifted in June 2010 to Tejgaon temporarily as the trust plans to reconstruct the Bisramagar to a 15 storied building, in two years time. The trust only funds insolvent wounded freedom-fighters registered with the trust. The services they claim to offer: a clean place to stay with proper food, bed, initial check-ups and recommendation to specific hospitals according to the patients' particular needs. The entrance to the Bisramagar, however, is dark and uninviting. The walls give off a dirty yellow hue from the 40 watt bulbs that seem to be growing dimmer. The corridors are too small for two people to walk through at a time and, as if in sarcasm, arrows are drawn in charcoal directing the way with 'welcome' etched above them. These arrows through the eerie corridors lead to various rooms all having rusty hospital beds, many with patients lying or sitting on them morosely. The inmates are all quite old, some on wheel chairs and others with crutches. It makes one wonder -- do our ill freedom fighters come to this place to be cured or do they come to fall ill? Further inside is a large room, with a small TV at one corner and a few sofas scattered around it. Mohammed Alim Uddin Mondol, who fought under Sector-9 during the Liberation War, slumps down on one of the sofas. "Nobody cares about us, even the health advisor is scarcely available; instead of staying at the office for at least three hours, they hardly even stay for half an hour," he says with a hint of frustration in his voice. The in-mates have no one to complain to or to voice their opinions. They say it is impossible to reach them. Ali says, "The authorities are almost impossible to reach even over the telephone. If you do finally get hold of one of them they just give you empty promises and leave it at that". Mondol who came here from Meherpur, Khulna has undergone two heart transplant operations, for a permanent pacemaker placement. He has been staying here from March 10, after being released from the National Heart Disease Institute. Mondol will have to stay at the Bisramagar until he is well enough to go back home but the circumstances of the place can only contribute to him feeling worse. As a heart patient he requires special care and diet, neither of which is available. There are no nurses, only ward boys whose duties are limited to taking patients to and from the hospital and cleaning the rooms. Mohammed Yakub Ali from Jamalpur, who lost his leg during the war, sarcastically remarks, as he limps about sweeping his room with a broom, "The big officers are the ward boys here. They do not listen to any one and are hardly available when we need them". Shahabuddin, the only cook, who has been working for 25 years at the Bisramagar, is responsible for cooking two-meals a day. He claims that he cooks fish and meat alternatively in the week. However, the freedom fighters argue that this is not the case. Kohinoor who is Mondol's wife, says, "Meat is never provided. Only fish is cooked with mixed vegetables and it is so badly cooked that we have lost our appetite for food" Not only does the food taste bad, but it is only cooked as per his whim. The fact that patients often have to eat specific types of food as per their medical needs is completely ignored. Mondol pays Tk 50 per meal, per day and has to eat whatever he is given. Kohinoor is allowed to cook in the kitchen if she wants but only if she uses her own utensils and ingredients. "We are here temporarily; it is not possible to get the things needed to cook from outside," she says. Abdur Rahman of Lalmonirhaat, who fought under Sector-6 during the Liberation War, came to the hospital for a throat operation. According to him, the authorities did not give him medicine after the operation at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BMSSU) hospital in December last year. He did not even get a room to stay in; he sleeps on the floor at night. "You have to buy or prepare your own breakfast; they do not make breakfast here," he says. Often he does not eat anything because it is too costly to get food from outside. Rahman does not have anyone to assist him financially. The only family he has is an unemployed son who is still studying. The lavatories are in the most deplorable condition: the nauseating stench hits one from yards away. Kohinoor says, "Women and men have to share the same bathroom, and as if that is not bad enough, the bathrooms have no lights. We use torches and mobile phone lights when we need to use the toilet".

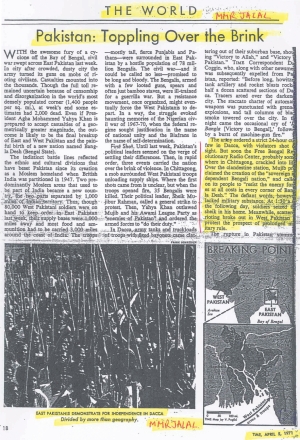

Anwar Hossain Bablu, the ward boy who has been working at the Bisramagar for the last sixteen years says, "Often there are water shortages, and a lot of mosquitoes and mosquito nets are not provided. Also as the Bisramagar is located in a commercial area, it gets very noisy. Because of the poor conditions, fewer people are coming to stay". There are currently 70 to 80 people residing in the two storied space of the Bisramagar. "It is also very difficult to transport these patients to and from their respective hospitals. There is no ambulance available and other modes of transport are difficult to obtain in a busy area like this," he adds. Bangladesh Muktijoddha Kalyan Trust is supposed to reimburse a certain amount of the medical cost to those who produce bills of their medical expenditures and can prove their financial need. Mondol, who has submitted his bills to the health advisor of the trust and has attained the required signature to be reimbursed, is now waiting for the money. "I spent Tk 1 lakh 42 thousand but Tk 50,000 spent on miscellaneous costs will not be reimbursed," says Mondol.Abudul Kuddus Mir, a freedom fighter from Mymensingh, accuses one of the directors of the welfare department and an accountant of the trust, of corruption. He claims that they have asked him to pay a bribe of Tk 15, 000 for signing a bill of a hearing aid machine worth Tk 58, 714". He adds, "The director uses the accountant to get them to pay the bribe. If they refuse to pay the bribe, the files go missing, or delayed or passed from one table to another for an indefinite period of time. The moment you pay them the bribe your bill will be passed and signed" he says. Mir has written to the Prime Minister, and other high ups in the Ministry of Liberation War Affairs, concerned authorities of the Muktijoddha Trust, journalists and media personalities, about the matter. When the accused director Mohammed Azizur Rahman Molla was approached, he denied any complaints of corruption before even being asked about it. "I do not see why these people have to complain so much, we have shifted the Bisramagar temporarily so that we can make the permanent building better," he exclaimed. He refused to speak, claiming to be "extremely busy". As one retraces the way back to the eerie corridors, one can also see other charcoal drawn arrows leading the way out with 'thank you' written on them. There are so many bitter ironies in those words that one feels relieved to be out of there. But the question remains, did our freedom fighters deserve such shoddy treatment for liberating our nation? 1971: In the Eyes of the World Naimul Karim “Vultures too full to fly perch along the Ganges River in grim contentment. They have fed on perhaps more than a half million bodies since March. Civil war flamed through Pakistan's eastern wing on March 25 pushing the bankrupt nation to the edge of ruin. The killing and devastation defy belief.”

Published by the Washington Evening Star on May 12, the above extract is one of many descriptions of the Liberation War of 71, provided by various international journalists. From narrating tales of the guerilla warriors to analysing the context of the war with respect to world politics, the various media reports, published during the nine-month-long struggle, provides in-depth details on the socio-political scenario back then, and in a way, manages to present a first-hand glimpse of the battle. Browsing through the media reports, one can notice a series of aspects being covered as the war progressed. In the initial stages, a majority of the international media organisations published stories describing the horrible plight of the Bengalis in East Pakistan. Several papers criticised the brutal steps taken by Yahya Khan and his army to curb the rising protests of the Bengalis. Describing the manner in which the Pakistani army conducted its mass killings, Gerard Viratelle of the French-based Le Monde, in an article published on June 10, wrote, “Hindu butchers in the old part of the city were decapitated with their own meat cleavers in their stalls.” The Pakistani army, according to the reporter, was trying to convince journalists that it was fighting for a noble cause and that the protest was a conspiracy organised by India. Recounting the panicky situation in the region, Viratelle wrote, “They (Pakistani soldiers) are gunning us down like dogs, a trembling Bengali muttered after glancing around to make sure no one was listening. People are picked up off the streets as soon as it grows dark. The army needs plasma for blood transfusions; it takes massive doses of their blood and abandons them half-dead in the streets.” Another article that depicted the mass-killings organised by the Pakistani army, was published in the Lebanan based - Al Hawadeth. The article entitled, 'War of Annihilation', wrote about the various ways in which the Pakistani army instilled fear amongst their Eastern counterparts.

Describing one such occurrence, it states, “The Pakistani officer stood in one of the small villages of East Pakistan and told the hungry public gathered around him: 'My men are wounded and I want some blood, I want volunteers.' Before waiting for a reply, the soldiers rushed forward, selected some young men, threw them on the ground and pricket them in the arteries, blood began to flow and it continued flowing until the young men died.” The Pakistani government defended themselves by claiming that their troops attacked rebels who only offered armed- resistance. However, a transcript of monitored radio messages between General Tikka Khan and other army units, published by The Times on 2nd June, disproved their stand. The following is an extract from the article: “Control: Well done. What do you think would be the approximate number of casualties at the university? 88: Wait. Approximately 300. Over. Control: Well done. Three hundred killed? Anybody wounded or captured? Sitrep (situation report). Over. 88: I believe only in one thing- 300 killed. Over. Control: Yes, I agree with you. That's much easier. Nothing asked nothing done. You don't have to explain anything. Once again, well done. Once again I would like to give you shabash to all the boys…” Following the reports on the mass killings, there were a series of reports published on the dreadful state of the refugees who were forced to leave their homes. Some of them died while walking towards their new destination. The fatigue and the unlivable conditions at the camps led to the deaths of thousands of refugees.

Describing their dire situation, an article, published by Life, on June 18, states, “They are dying in such numbers we can't even keep count, said an Indian social worker. It could have been avoided if the govt had told them where to go. But they just keep walking and walking in the hot sun. They became exhausted. They drank from infected pools. Often they die in a single day because they are so weak.” A series of reports were also published on the 'Mukti Fauj' or the guerilla bands. Terming them as East Pakistan's only hope for survival, several papers narrated their heroic encounters with the Pakistani army. A news-feature from the Observer wrote about the participation of Bangladeshi women in the liberation war. Another article wrote about the various training disciplines imparted to the guerilla outfits. An extract from an article entitled 'With the Bangladeshi Guerillas' clearly describes the fearlessness with which they fought against an armed Pakistani army: “These young men (guerillas) are now convinced that big powers, whether paying lip service to the ballot box or the ideology of revolution only recognize the reality of force.” In a similar manner, various other articles from the Guardian, Times, Far Eastern Economic Review etc. published stories of how the guerilla warriors trained themselves. While majority of the media organisations initially declared the war of 1971 as a civil war, their opinions changed as the war progressed. Several reports published later on, described the atrocities committed by the Pakistani Army as genocide. Comparing the war to a Greek tragedy, a British paper denounced the Pakistani government. Despite strong evidence, the atrocities committed by the Pakistani army in 1971 have still not officially been declared as genocide. The descriptions by several journalists, who have termed the horrific killings of 1971 as a clear violation of human rights, have been overlooked by the United Nations and other international organisations. Perhaps an extract from an article written by Alfonso Gonzales, which although was written in September, 1971, for El Commercio, best describes the political games played by the powerhouses of the world today. “The devious and deceitful maneuverings is developing with the neglect of the main problem: the human being. Not one of the countries who have granted help to those unfortunate millions, have condemned the monstrous genocide committed there with such fury and ruthlessness. Nobody has spoken ; not one has done their duty of defending the right to life which is clearly the focal and fundamental point in the Charter of Human Rights.” UPL'S 71 BOOKS Liberation War from Different Perspectives The books published by UPL over the last 37 years offer previously unknown and often alternative histories of the birth of Bangladesh. Some of the books include oral histories and completely new perspectives on the war. Muntasir Mamun's works explore the mindset of the Pakistani civil society and the elites who designed and implemented the war in the first place. On the 40th year of independence, UPL is featuring 71 titles on 1971 with the aim to encourage the post-71 generation to read the various perspectives of the liberation war narrated by different actors. Highlights of UPL's series of books on liberation war: Mooldhara '71 The book is a valuable addition to the history of our liberation war. In this detailed work, the author has provided an insight into the political, military and diplomatic workings of our liberation war. His chronological narration of the events is replete with voices of the people who witnessed the war. Many unknown episodes of the war have been described here. Quite a lot of things about the nature of our liberation war fall into place when we understand those unknown events. The author, Maidul Hasan, was a close friend and confidant of the first prime minister of Bangladesh, Tajuddin Ahmad who consulted with him about the wartime policies and diplomacy with India. The book is a trusted source of reference in the history of our liberation war. “During the nine months of the liberation war,” the author says, “Tajuddin Ahmad was at the centre everything and worked with utmost sincerity and honesty”. However, Hasan regrets that Tajuddin Ahmed said almost nothing about his own contribution to the war. As a consequence, a significant part of our liberation war is still in the dark. The book is an attempt to bring to light those unknown happenings of the liberation war. Pakistan Jakhan Bhanglo

The translator, ATM Shamsuddin, is well known for his political activism and translations of famous thrillers. Ekattorer Smrity

Author: Basanti Guhathakurata, Price: BDT 180, First Published: 1996, ISBN: 978 984 8815 39 7, Cover Type: Hardcover, No of pages: 162, Status: Available The author suffered the horrors of Mrch 25, 1971 and the death of her wounded husband. In her struggle to survive, she has witnessed the barbarity of the war. In this book, Basanti Guhathakurata tells the tale of liberation war to the readers of the post-war generation. The author was a teacher and a widely read voice advocating women's rights to education. She also won many prestigious awards for her works in literature and social welfare. Muktijuddhe Kasba

The study was conducted by the historians, economists and social workers of Muktijuddha Gabeshana Kendra. Pakistanider Dristite Ekattor

We do not know if the general public of Pakistan enjoy enough freedom to talk about that period openly. The book is a compilation of interviews of 11 military and non-military personnel and bureaucrats. The interviewees also include nine politicians and eight members of Pakistani civil society. In brief, the book presents the opinions of people who had direct influence on the policies taken by the then West Pakistani government. The book is undoubtedly a reliable source of reference for people who want to understand the perspective of the Pakistanis during Bangladesh's liberation war. The book was edited by renowned scholar and researcher Muntasir Mamun and Mahiuddin Ahmed. Shei Shob Pakistani

The people of Bangladesh won the war. But they had paid the price. It is impossible to think of a torture that has not been inflicted on Bangladeshi people by the Pakistani Army. The book provides insight into the Pakistani elites who designed and implemented the war on their own people. With Muntasir Mamun's mastery in narrative techniques, the book has become remarkably lucid and at the same time insightful. The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh - Memoirs of an American Diplomat

The book reflects a deep commitment to freedom on the part of the author and reads like an epitaph for the martyrs of struggle of the Bengali people. In 24 chapters the author chronicles the events of 1971 as he and the staff of the United States Mission in Dhaka saw them unfold. Blood had to wait until December 1998 for the State Department to declassify the documents, telegrams and other messages related to this period before he could use them. The story that emerges portrays large and vastly important drama of the real protagonists of the period: General Yahya Khan, ZA Bhutto and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. From East Bengal to Bangladesh: Dynamics and Perspectives

Bangladesh emerged as an independent country in 1971 through a violent liberation war leading to the dismemberment of former Pakistan (1947-1971). Former Pakistan came into existence when two Muslim majority areas of the British Indian Sub-Continent, East Bengal and Northwestern India (re-named as West Pakistan) formed one country. However, prior to that Union, for historical reasons, West Pakistan had developed itself as a feudal-military-tribal/caste dominated socio-political culture with clear preference for authoritarian and centralised rule while East Bengal had emerged as a significantly successful fighter, challenging its own feudal system with distinct preference for participatory democracy, vertical social mobility and further social change. The clash between the peoples of the two regions at two levels of historical development scale, therefore, seemed inevitable. This book explains the dismemberment of former Pakistan and the emergence of Bangladesh in a wider canvas of historical challenges, struggles and dynamics that had constantly worked in the background. This book is a part of the Road to Bangladesh Series which is designed to present published accounts of the background to the emergence of Bangladesh. Books in the series should be an invaluable collection for those interested in South Asian affairs, particularly students and scholars of politics, economic development and social transformation. Surrender at Dacca: Birth of a Nation

The campaign for the liberation of Bangladesh was short and swift, spread over some thirteen campaign days, conducted in riverine terrain highly suitable for defence. Outlining the evolution of the strategy for the campaign, the writer details the selection of thrust lines using subsidiary dirt tracks that bypassed centres of resistance and opened up axes of maintenance later. The objectives selected were communication centres in relation to the geopolitical heart-Dacca. A concise account of the execution of the campaign is given. He highlights the role of the Mukti Bahini and the great contribution they made towards the liberation of their country. He describes the pressures exerted at the Security Council and the pro-Pakistani stance of China and the United States as well as giving a first-hand account of the negotiations and the signing of the Instrument of surrender. Witness to Surrender

He has produced an authoritative narrative, dispassionate in tone and firmly anchored in facts.

The Separation of East Pakistan - The Rise and Realization of Bengali Muslim Nationalism

The book provides penetrating insights into the economic dimensions of the chasm between the erstwhile East and West Pakistan that eventually led to the cleavage and the conflict that marked the final parting of the ways. The focus of Hasan Zaheer's study is more on what he feels were the internal factors that, in his view, somehow inexorably widened the mental distance between East and West Pakistan with the result that by 1970 and following the military action of March 25, 1971, the situation had reached a point of no return. Relying on primary sources - personal experience, unpublished material, and conversations and interviews with those directly involved in the 1971 crisis, Zaheer has provided a thoroughly documented account of events on the national and international fronts in a dispassionate manner. Compiled by AKRAM HOSEN MAMUN MARCH 1971 Syed Badrul Ahsan 25 March 1971 dawned in unease, both among the Bengali political leadership and the population as a whole. From the early part of the day, rumours began to make the rounds of an imminent army operation against the Bengali nationalist movement, which was now vociferously demanding that Mujib declare the independence of the province. The leaders of the Awami League waited to hear from the junta, but when nothing came from that side and the day slowly progressed to afternoon, Mujib and his colleagues knew that the end had drawn nigh. By early evening, the Awami League had given a call for a general strike all over the province on the following day even though it did not quite know the turn conditions would take between the evening of 25 March and the beginning of 26 March. As dusk fell on 25 March, news began to circulate that President Yahya Khan and his team had flown off to West Pakistan. It did not take long for the Awami League to confirm that the leader of the military regime had indeed left Dhaka. His departure was the earliest hint that a major crackdown by the army could be only hours away. Angry Bengalis, in their determination to resist the soldiers should they venture into the streets, erected makeshift barricades at important points in the city. In the Dhaka University campus, in Motijheel, the business district of the city, and on the road leading out of the cantonment into the city, young Bengalis struck down trees and bamboos and picked up stones and bricks to litter the roads with obstacles that would make it difficult for the soldiers to break through. It was naivete at work, with few citizens really aware of the terrible force the army might use in its attack. But it was, at the same time, a desperate move on the part of a population which was now confronted with circumstances that threatened the political movement which had gone on for the past nearly one month. From various parts of the city, slogans of Joi Bangla, victory to Bengal, made popular by the Awami League over the previous couple of years through its emphasis on the Six Points, were heard. But, at the same time, the streets cleared quickly as citizens went through deep foreboding at how the night would turn out to be.

At his residence in the Dhanmondi residential area, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was being difficult with his party colleagues and workers, all of whom wanted him to make his exit from the city and lead what they saw as a coming struggle for independence from Pakistan. The Awami League leader, uncharacteristically pensive and not wasting many words in his defence, refused to entertain any thought of going into hiding. He was, he told his party men, the elected leader of the majority party in the national assembly and therefore could not be expected to escape. Besides, if he left Dhaka, a maddened army would burn every home down looking for him. He preferred to wait and let the army take him, as it had in earlier times, into custody. But he told the assembled leaders and workers that they should fan out into the country and prepare for the coming struggle for liberation. As the evening deepened, Awami League leaders, journalists who had come to observe his next moves, friends and others left Mujib's residence. He was now in the company of his family --- wife Fazilatunnessa, daughters Hasina and Rehana and sons Kamal, Jamal and Russell. As the first sounds of gunfire were heard from the approach out of the cantonment, his elder daughter Hasina remembered, Mujib sent out a message through wireless proclaiming Bangladesh's independence. It was brief and to the point. With the army on its way, as Mujib knew, the elected leader of the majority party in Pakistan's national assembly and spokesman of the seventy five million Bengalis inhabiting the province of East Pakistan had the following directive transmitted to the outside world, which of course at that point was symbolised by the land he sought to make free: “This may be my last message. From today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh, wherever they might be and with whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from Bangladesh. Final victory is ours.” Bangabandhu's declaration of independence was swiftly borne out by a report distributed on 26 March by the US Defence Intelligence Agency to the White House Situation Room, Department of State and other government agencies in Washington. Titled 'DIA Spot Report', the agency noted thus: 1. Pakistan was thrust into civil war today when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman proclaimed the east wing of the two-part country to be “the sovereign independent People's Republic of Bangla Desh.” Fighting is reported heavy in Dhaka and other eastern cities where the 10,000-man paramilitary East Pakistan Rifles has joined police and private citizens in conflict with an estimated 23,000 West Pakistani regular army troops. Continuing reinforcements by sea and air combined with the government's stringent martial law regulations illustrate Islamabad's commitment to preserve the union by force. Because of logistical difficulties, the attempt will probably fail, but not before heavy loss of life results. 2. Indian officials have indicated that they would not be drawn into a Pakistani civil war, even if the east should ask for help. Their intentions might be overruled, however, if the fever of Bengali nationalism spills across the border. 3. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is little interested in foreign affairs and would cooperate with the United States if he could. The west's violent suppression, however, threatens to radicalize the east to the detriment of US interests. The crisis has exhibited anti-American facets from the beginning and both sides will find the United States a convenient scapegoat. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, having sent out the declaration of independence, climbed the stairs leading from his library, from where he had sent out his message, and joined his sombre family on the first floor. He was poised, almost at peace with himself. But he knew, as well as anyone else in his family and among his colleagues, that the future for him was uncertain. The state of Pakistan was determined to get him and possibly finish him off. The rest, as they say, is history. The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |

Author: Maidul Hasan, Price: BDT 325, First Published: 1986, ISBN: 978 984 8815 63 2, Cover Type: Hardcover, No of pages: 319, Status: Available

Author: Maidul Hasan, Price: BDT 325, First Published: 1986, ISBN: 978 984 8815 63 2, Cover Type: Hardcover, No of pages: 319, Status: Available The book is a compilation and translation from Memoirs of Lt. Gen. Gul Hassan Khan. Gul Hassan was the last commander-in-chief of the Pakistani army. He was the army Chief of General Staff during General Yahya. As an important figure of the ruling class, he witnessed the melodramatic events of history from the centre of power. The rise and fall of Aiyub, Yahya, the war of '71, the fall of United Pakistan, birth of Bangladesh—everything happened before his eyes. The translation of his memoir especially the last three chapters will provide new insight into the history of our liberation war.

The book is a compilation and translation from Memoirs of Lt. Gen. Gul Hassan Khan. Gul Hassan was the last commander-in-chief of the Pakistani army. He was the army Chief of General Staff during General Yahya. As an important figure of the ruling class, he witnessed the melodramatic events of history from the centre of power. The rise and fall of Aiyub, Yahya, the war of '71, the fall of United Pakistan, birth of Bangladesh—everything happened before his eyes. The translation of his memoir especially the last three chapters will provide new insight into the history of our liberation war.

For its location, Kasba became a geopolitically important place during the liberation war. The book incorporates the shocking experiences of the people who saw the cruelty of Pakistani army. It is also a record of the oral history of the liberation war. The interviewees include farmers, labourers, shop keepers, students, teachers, the members of Bengal Regiment and political activists. In short, the book traces the people for whom the war was an unforgettable event. The picture of struggle in different regions of the country was not similar in 1971. The study provides substantial information about the situation of Kasba at that time.

For its location, Kasba became a geopolitically important place during the liberation war. The book incorporates the shocking experiences of the people who saw the cruelty of Pakistani army. It is also a record of the oral history of the liberation war. The interviewees include farmers, labourers, shop keepers, students, teachers, the members of Bengal Regiment and political activists. In short, the book traces the people for whom the war was an unforgettable event. The picture of struggle in different regions of the country was not similar in 1971. The study provides substantial information about the situation of Kasba at that time. We hear little of the people who attacked Bangladeshi civilians on 25 March, and massacred them for nine months with unprecedented viciousness. We also do not know how the people of West Pakistan interpreted the events of 1971. Their indifference to the genocide in Bangladesh also remains inscrutable.

We hear little of the people who attacked Bangladeshi civilians on 25 March, and massacred them for nine months with unprecedented viciousness. We also do not know how the people of West Pakistan interpreted the events of 1971. Their indifference to the genocide in Bangladesh also remains inscrutable.  The book is written in the narrative form. Muntasir Mamun seeks to locate the Pakistani perspective on Bangladesh's liberation war.

The book is written in the narrative form. Muntasir Mamun seeks to locate the Pakistani perspective on Bangladesh's liberation war. It is an account of the emergence of Bangladesh seen through the eyes of a sympathetic American diplomat based in Dhaka during 1970-71. Archer Blood glorifies the independence struggle of Bangladesh as a “Transformation of seemingly forlorn Dream into a bright shining Reality”.

It is an account of the emergence of Bangladesh seen through the eyes of a sympathetic American diplomat based in Dhaka during 1970-71. Archer Blood glorifies the independence struggle of Bangladesh as a “Transformation of seemingly forlorn Dream into a bright shining Reality”.

Throughout 1971, Siddiq Salik was in Dhaka as a uniquely privileged observer and participant in the political drama which culminated in the Indo-Pakistan war and the creation of Bangladesh. During his two years as a prisoner of war, he was able to ponder and digest the facts and analyse the complex circumstances which underlay the events.

Throughout 1971, Siddiq Salik was in Dhaka as a uniquely privileged observer and participant in the political drama which culminated in the Indo-Pakistan war and the creation of Bangladesh. During his two years as a prisoner of war, he was able to ponder and digest the facts and analyse the complex circumstances which underlay the events.