| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 40 | October 21, 2011 | |

|

|

Special Feature Incorporating the “Others” into the Mainstream Sushmita S Preetha

Mou's kohl-lined eyes well up with tears as she explains what it means to be a hijra in Bangladeshi society: “We are shunned by everyone – our family, friends, the society. No one understands the pain or suffering we go through; no one even thinks we deserve compassion.” Mou is a self-identified hijra, who has had to experience discrimination all her life as a result of her ambiguous gender and sexual expression. She adds, “But we are also human, no? We need to be loved; we need rights and entitlements like everyone else.” Mou's statement echoes the sentiments of thousands of hijras residing in Bangladesh, who lead stigmatised and impoverished lives. Despite systematic discrimination in economic, political and cultural spheres, they have received very little attention from the media, civil society or the government. For the most part, they have been invisible in mainstream discourses as anything but objects of derision. Over the past few months, however, a group of senior government officials have undertaken a pilot project titled “Integration of the Transgender Population into Mainstream Soceity” to bring issues of hijra marginalisation to the forefront of mainstream discourses on gender and sexuality. It is the first attempt by any government administration in Bangladesh to address the hardships faced by this minority community. In South Asia, a hijra is usually considered to belong to "the third gender,” occupying a liminal space between male and female. For the most part, hijras are phenotypic men who wear female clothing and, ideally, renounce sexual desire and practice by undergoing a sacrificial emasculation. Not all hijras, however, undergo this operation referred to as nirvan (meaning “rebirth”). They define themselves as being neither male nor female, constituting a separate category altogether. Pushpita, a hijra herself, explains, “People try to define us based on their own understanding of what it means to be a man or a woman, but it's very limiting. It does not fully grasp the intricacies of our lives.” Hijras can be eunuchs or hermaphrodites, or neither, or both. They can be born intersexed or born “male” (some may undergo castration but others may not); they may dress up in women's clothes and engage in feminine practices without thinking of themselves – or desiring to be – “female;” they may have male lovers and sexual partners, without ascribing the identity of “gay” to themselves and/or their sexual partner(s). To be a hijra, or to identify as such, therefore, involves negotiating complex and often contradictory terrains of selfhood. Most hijras I spoke to stated that, from a very early age, they preferred to dress up in feminine attire, play with girls and participate in household chores traditionally assigned to women. One informant said, “I knew I wasn't like the rest of the kids that I grew up with. I looked like a boy, but I always felt like a girl and insisted on acting like one.” Their families did not accept this deviance from expected gender norms, although the degree to which their families pressured them to change varied from person to person. As Pushpita asserts, “In the beginning, my family didn't say anything. They thought once I grew up, it would go away. They beat me from time to time to make me give up my feminine ways. Over the years, the berating got worse as other people in the community and extended family started to insult them [parents/family]. Ultimately, they said I couldn't stay under the same roof unless I found a way to be 'normal.' I was bringing shame to the family.” Pushpita's story speaks to the societal pressure that most families face in nurturing a male bodied adolescent with feminine attributes. Although Pushpita still remains in touch with her family, wearing male attire whenever he goes to visit them, many hijras do not maintain their relationships with their families. For some, it is an active decision to drift off because they are tired of living a lie and want to find a place where they can belong; for others, there is no such choice as their families disown them either prior to or once they join the hijra community.

For the most part, hijras do not have access to “regular” jobs because of their marginal status in society. As Laila notes, “No one wants to even walk on the same side of the road as us. Do you think they'll really give us a job?” Most of them, therefore, earn an income in one of three ways: through badhai bajaar tola (harassing people on the streets for money) or sex work. Badhai, singing and dancing during weddings and childbirths to bless newlyweds and newborns, has been the traditional profession of hijras for a long time and is central to the way they define themselves. For the past decade or so, however, hijras have found it increasingly difficult to engage in badhai work as a result of the changing nature of Bangladeshi society, putting severe constraints on their ability to earn a living. As a result, many hijras now resort to bajaar tola, which means that they go from shop to shop heckling people for money. Having run out of other viable or profitable options, many hijras market and perform their disreputable status in order to instil fear and anxiety among the public, so that people are forced to give them money to get rid of them. Incidents of hostility are not uncommon, and serve to perpetuate people's prejudices against hijras. It becomes a cyclical process whereby discrimination from others leads hijras towards aggression, and their aggression, in turn, further marks them as crude and debased beings in the public imagination. Hijras suffer from a range of exclusionary practices, from limited access to jobs, education, legal and health services to restricted access to voter rights, legislations, and decision-making in policy. The Bangladeshi state itself actively participates in a process of hijra exclusion. For instance, the state only recognises two sexes, male and female; as such, hijras are not recognised in official documents even though they constitute a socially recognised – if never a totally accepted – category in Bangladesh. We still have not repealed colonial anti-sodomy laws and laws that make cross-dressing illegal, which speak to the state's ambivalent attitude towards its sexual minorities. Even the civil society, which usually play a prominent role in mainstreaming issues of gender and related injustices, have been silent on issues of hijra discrimination. In Bangladesh, most of the NGOs that do work with hijras focus their attention on issues related to HIV/AIDs and safe sex rather than on social mobilisation and structural change. Even NGOs that work specifically on gender issues do not adequately address the concerns of hijras. It is in this context that a team of six government officials at the deputy secretary level undertook a pilot project titled “Integration of the Transgender (Hijra) Population into Mainstream Society.” Approved by the Ministry of Public Administration, the project is being implemented through funding from Ministry of Education's “Skills Development Project.” The team leader of the project, S M Ebadur Rahman, Deputy Secretary of Economic Relations Division, says, “Every year, senior government officials are sent on a training course. To fulfil the requirements of the training, Managing AT the Top2 (MATT 2), each team has to come up with a pilot project on an issue they deem to be important. Our team, Team E, Batch 32, decided to work on transgender issues since the government has never really paid proper attention to plights of these communities.” Rahman mentions that initially there was a lot of resistance from his colleagues about his team's concept. He says, “Everyone was sceptical about our project. They asked us why we wanted to work on this issue when there are so many other problems in Bangladesh.” However, Rahman and his team persevered and convinced people about the importance of designing and implementing this project.

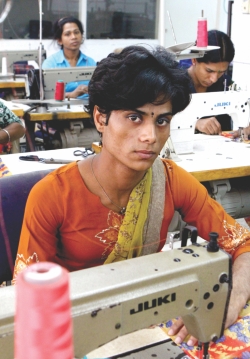

The six members of the project are: S M Ebadur Rahman, Md Zafar Iqbal, Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Public Administration (MOPA), Md Ayub Hossain, Director of Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), Md Shamsul Alam, Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Education (MOE), GSM Jafarullah, PS to Secretary, ACC, and Md Mujibur Rahman, Senior Assistant Secretary, MOE. According to the team members, “Transgender people have gender, sexual and citizenship rights that need to be protected. The pilot project is expected to show how people of transgender community can be made ready for employment like any other person through skill development despite social taboos.” The project seeks to integrate the transgender (hijra) community into the mainstream society. The main objectives of the project are: 1) to take necessary steps to create mass awareness about the transgender population; 2) to give skills development training to 30 hijras and provide employment opportunities for them; and 3) to establish a trust/foundation for the welfare of the transgender community. Team leader, Ebadur Rahman says that the team has met with the transgender community leaders to assess their training needs and to hear their demands. Currently, 30 hijra members are undergoing a one and a half month long skills development training course. Seven of them are undertaking a computer course, thirteen of them are learning sewing and design and ten are receiving beauty parlour training through Persona. Zakir Hossain, trainer of UCEP–Bangladesh says, “When I was first asked to train them, I educated myself on transgender issues so that I could teach them in a respectful way. In order for them to feel that they are normal, we must treat them like they are normal.” The other trainers also reiterate this view and insist that their new students are respectful, smart and hardworking. Trainer Khushi says, “In the beginning, I was a little apprehensive, but once I started taking the class, I realised how mistaken I was about them. They are very fast learners. Because they have both feminine and masculine attributes, they signify the best of both worlds.” The trainees are excited to finally have an opportunity to receive this training. Mou asserts, “We all want to lead dignified lives, so we are obviously very happy to have this chance to learn something new, but we hope that we can get jobs after this training is over.” There seems to be a lurking fear among the trainees that they wouldn't get the jobs that they have been promised. As Adori says, “So many people come and tell us they will help us. But in the end, we are left to fend for ourselves. Who will guarantee that we get jobs after we finish the training?” All the trainees want a chance to prove themselves and have a shot at a regular life. They think that if they can get access to government jobs, the rest of society will begin to accept them as ordinary citizens. Rahman and his colleagues have ensured the trainees that they will find them suitable jobs, but whether or not they fulfil their promise remains to be seen. The project has also initiated a mass awareness raising programme to change the negative views of people against the hijra community. Zafar Iqbal, Deputy Secretary (MOPA) explains that they have been organising seminars, rallies, advertising campaigns and publicity drives. There are ads and talk shows on TV channels and ads in major newspapers with the messages: “Hijras also need separate legal recognition along with men and women...” The team members have organised a rally to be held this Friday, 21th October with members from the hijra community, civil society and the government. The team hopes that the rally will bring people from different segments of society together and motivate them to work collectively on the issue of transgender rights.

In order to ensure sustainability of the project, a foundation has been set up with members of the hijra community. A seven member committee was formed with hijra representatives from community organisations including Badhon Hijra Shongho, Shustho Jibon, Shomporker Noya Shetu and Shocheton Shilpi Shongho. Joya Shikdar, member secretary of the foundation and prominent hijra activist, says, “This foundation has given us a platform. Now we can form a movement collectively to realise our demands.” Shikhdar says that they have demanded that hijra communities from different districts in Bangladesh be also included in this network. Evan Ahmed Kotha, cultural activist and head of Shocheton Shilpi Shongho, says: “Finally we have gotten a chance to make an impact on a national level. Even though some of us have been working on these issues for years now, we have not been able to make much progress because of lack of resources.” Both Shikhdar and Kotha are grateful to Team E for undertaking this project. They don't know how to thank them for giving us recognition and acknowledgement. However, they want to make sure that this project is the beginning rather than the end of a movement towards a non-discriminatory Bangladesh. This project is certainly a commendable one, but one hopes that the efforts to include the transgender community into the social, political and economic spheres of Bangladeshi society do not stop when the project comes to an end. We need to bring about long lasting structural changes in society by challenging hegemonic understandings of gender, sex and sexuality. Till that happens, the state needs to give special protections to its sexual minority populations and repeal laws that target and harass the transgender community. In addition, the state should recognise hijras as a third gender in its official documents, so that they can enjoy the same rights and entitlements as men and women. The civil society, too, should be more receptive towards sexual minorities and work in solidarity with hijra community activists to ensure better access to education, employment, and legal and social services for the hijra community. And the rest of us, those who enjoy the privileges of belonging to the sexual majority, must change our negative perceptions towards the transgender communities and treat them with the respect and love that they deserve.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |