| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 34 | September 09, 2011 | |

|

|

In Retrospect About Mrs Val Andrew Eagle

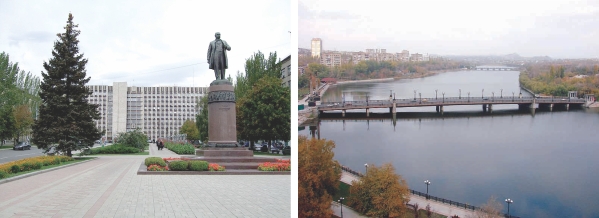

There were gloves and a scarf in it, not to mention a woolly hat, the day Val took me to their family apartment to her mother. Donetsk in Ukraine is a city of about two million people and four full seasons. It has forty-plus summers and minus-twenty winters and we'd not reached the summer yet. It took me a while to come across her name these years later. It's Tanya. I suppose it's a peculiar habit to get about renaming people quite independently of whatever arrangement of letters the rest of the world has granted them, but I often do. It's the reason her regular name didn't come easily, because I never used it. It may be my mother's inheritance, because in her family several of the names in use have no correspondence to birth certificates. As with Bengali newborns, in my mother's family allocating names is like clothes shopping. Names need trying out first, it takes them a while to fit and sometimes they get changed before they suit. It's unfortunate for it's neither very creative nor as a title correct, but by virtue of being Val's mother it was Mrs Val that settled in to be her name. There is significant doubt she knows I call her that but none that she'd forgive me for it. Mrs Val lives in the usual Soviet apartment block, tall, slightly dour and similar to all the others thereabouts. I lived in one too, that the language centre had rented for their native-speaker English teacher. Val and I followed a path of worn damp earth to the stoop of the building. The block featured one of those gorgeous old lifts of the criss-crossed iron outer door variety, of the laminated plywood inner door variety: all doors to be opened by hand. With some luck once all the doors were shut again the little light in the lift would turn on automatically and with luck, upon pressing the chunky black plastic button for the floor the little engine would whirr. Mrs Val seemed a little nervous when she opened the door. I was too. In part it was because like her daughter and I, she is an English teacher, though in her achievements on an altogether higher level. Ukrainian English teachers: how I admire them! To think they'd studied the language for five years at university without the opportunity to converse with a native-speaker. In Soviet times there'd been the occasional guest lecturer but because of politics it had hardly been possible to have a chat one to one. On the earliest occasions some of them spoke with me, there remained slight hesitation about how their language skills when confronted with a native would fare. I took it in, Mrs Val and the sitting room. Isn't it funny how new experiences can sometimes gently accidentally touch upon a childhood moment and bring to the present warmth and light? Mrs Val made me remember the elephants.

When I was six or seven one of my father's work colleagues used to live on the corner down the street. They were family friends, Mr and Mrs Montgomery and my parents used to take me there when they'd go to visit. While in that house there hadn't been much for a kid to do I used to enjoy it: it had a kind of happiness in it that used to rub off. So while they spoke about adult things I would busy myself with the elephants, the big, medium and little black wooden ones that must've emigrated from Africa to settle as a herd by their fireplace. 'Be careful with the elephants,' my father used to say. At a basic level it was the red of Mrs Val's hairdo that linked her with Mrs Montgomery but more than that it was the sitting room ambience. Mrs Val spoke gently with an accent rich in that Russianness is East Ukraine's history. She spoke about changes in the classroom: how teachers were once sufficiently dedicated to take it upon themselves to visit a family in person to inquire after an absent student. She still had that quality. From that and because of the tapestry on the wall I thought of Iran. The tapestry was one Iranians might choose; and similar words I'd heard from her Iranian colleague, Farhonde. Mrs Val was calmer; Farhonde specialises in energy and not a day under sixty she was when she started the snowball fight on the slopes of Damavand. Yet they were alike: teachers to the bone. After the Soviet collapse the economics of things were more than tight for teachers. In the larger Kyiv, salaries might barely cover the cost of commuting. In Donetsk the situation was hardly better. Mrs Val used to spend her free time at her small land plot on the city outskirts, tending potatoes. I know she enjoyed that but there were times it'd been more necessary than it should've been; and of course the pension system she'd spent her whole working life anticipating was mostly gone. Donetsk is a city of mines: even inside suburban areas; and from Mrs Val's balcony you could see slag heaps on the horizon. I considered myself a bit of a miner, although while others went underground for coal the minerals I sought were new culture and new learning. Of the other sort of mineral I cannot say, but in what I fossicked for Donetsk was incredibly wealthy. "When I was a kid," Val said, 'I used to think those heaps were the mountains of Georgia.' Distances reduce as we grow. "Well…" it was the silvery word Mrs Val used, drawing it out slightly and peppering it through the conversation. She'd crafted it to mean anything: sometimes it acknowledged we shared an imperfect world; sometimes it was a solitary drum beat to mark time; but mostly that tiny word held an exact and easily comprehensible meaning: nobody brings to it the adaptability she does. "Well…" she said. It was time to prepare lunch. I don't know, just I followed her and in the kitchen we sat making pilmeni, Russian dumplings, together. We spooned the meat filling into the folded pastry and crafted little scalloped edge packets with our fingers. Mrs Val's pilmeni were neat and exact; mine were inexperienced and shoddy. And I was at home. I remember the salt. Val had left the living room during the meal and after some minutes, returned. "What have you done with it?" she asked her mother, a little demandingly. 'I've hidden it.' Mrs Val said, unapologetic, and, turning to me added, "she eats too much salt." "Yes, she does," I said without thinking. In the classroom it's Mrs Val I think of: if ever I managed to be half the teacher she is then I did well. Even without seeing her teach I knew it, that she was the professional high-water mark. And isn't it nice to imagine a Mrs Val world? There'd be no battlefield, only the classroom. In Australia, the Federal Police wouldn't have recently completed jungle training to prepare to potentially shoot pellets at the Afghan asylum seekers who arrive by boat, many of them children. In a Mrs Val world there'd be no need to refuse to help people or expel foreignness. "Well…" After several hours we left, and walking down the stairs I said, 'Your mother is wonderful. So I don't know what happened to you!' Val stopped in her tracks, shooting an arrow of a glare; but with me, she had long since lost her licence to misunderstand the meaning was opposite, and be genuinely offended. It's the way of things. And in Dhaka we're reduced to the text box. After chatting away with Val a few months ago, as we were winding up, I typed, 'and when you see your mother, tell her I love her.' "I know," the message came back, 'and she loves you too.' "Well…"

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||