| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 31 | August 12, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story

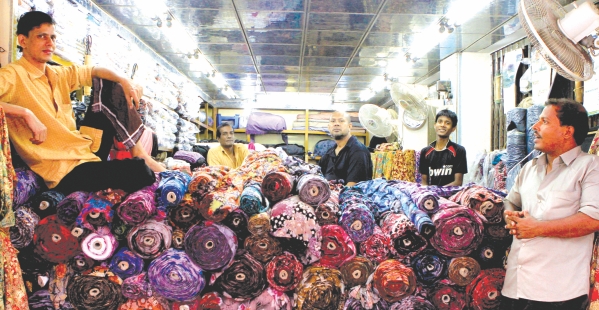

In the Folds of Islampur Islampur Road, which runs parallel to the River Buriganga connecting Banglabazar with Mitford Road, is home to the largest wholesale market for cloth in the country. With numerous thread-like lanes on either side of the road crowded with pedestrians, trucks, pick-up vans, cycle vans, rickshaws, three-wheelers, motor bikes, and cars, Islampur almost takes one's breath away, literally speaking. The perpetual bustle of the area accentuates our overt infatuation with one of the basic necessities of civilisation — clothing. Tamanna Khan Photos: Zahedul I Khan

Although the legendary Dhakai Muslin can no longer be found in the innumerable stores located inside the newly constructed high-rises or the dilapidated buildings from the past, anything from hospital bed-sheets to expensive garment materials are available in Islampur. Saber Hossain Malek, a clothes store owner from Bhaluka, Mymensingh, comes to Islampur regularly to buy printed and plain fabric for shalwar-kameez, trousers, shirts, and panjabi. “It is easier to buy from Islampur than from other places because of the variety and quality of cloths available here. Even the prices are low. I can also buy on credit from some of the shops,” he states. Islampur acts as the hub for the fabric business. Most of the customers in Islampur come from different district towns of the country. Haji Muhammad Lutfur Rahman, owner of New Moon Fabrics that sells curtain and seat cover, says, “Islampur is the main sales centre for cloth, the other sales centre is in Baburhaat. But the quality at Baburhaat is low. So customers from villages usually go there while retail cloth shop owners from the cities come here.” Fifty-two-year-old Lutfur inherited the shop from his father who started the fabric business during the Pakistan period. He says Islampur's rise as a wholesale market for cloth began during the Pakistani period, reaching its height after liberation. The grey-haired Mohammad Yakub, who often visits Lutfur's shop from the other side of the Buriganga, reminisces: “Once the Nawabs of Dhaka treaded this road in their horse drawn carriages and shopped at the fancy shops on both sides of the road.”

The ruins of the Nawab-bari gate now lead to rows of tiny cloth stores, selling both retail and wholesale fabrics to customers who throng the market for Eid shopping. Among the group of university students and burkha-clad women haggling with the street side shop owners, it is hard to find the likes of the Nawab family. Neither do the muddy lanes running alongside deep ancient gutters, overflowing with sludge, help in conjuring up the lost aristocracy of the place.

Romel, owner of Samantha Fabrics, situated in one of the markets inside the crumbling Nawab-bari gate, acts as a middleman buying excess fabrics from ready-made garment factories and selling the same to tailoring shops. “Large stores like Cats Eye, Seal, Rex and Westecs also buy from me for making pant pieces (trousers),” he says. He cannot say where the fabrics are originally from as the exporter's sticker are no longer to be found on the rolls. “The quality of the fabric is judged by its thickness and the quality of thread. The price of the material depends on the construction of the thread,” informs Romel. However, he adds, tailors do not understand the measurement of the thread and buys fabrics based on colour requirement. Unlike Samantha Fabrics, Selim Reza, manager of Alim Fabrics buys goods from import agencies in Islampur, which bring in materials from Japan, Thailand and China. However, they also keep local fabrics from Baburhaat and Narshingdi textile mills. As a result the price of materials in Alim Fabrics ranges from Tk 60 to Tk 400 per yard.

Though foreign fabrics mostly from Asian countries are available in Islampur, almost 80 percent of the merchandise comes from textile mills situated in Narsingdi, Madhobdi, Roopganj and the other districts near Dhaka, informs Abdus Sattar Dhali, president of Islampur Bastro Babshayi Samity (Islampur Cloth Traders Association). Trucks and pick-up vans carrying merchandise from these districts park right on the road since most of the markets do not have any parking lot. Middle-aged Nuru Mia, standing on top of bales of different shades of polyester, describes his business. “I have been coming here with merchandise from Madina Mill at Bhulta, Gausia for the last twenty years. I make two trips daily supplying these fabrics to hundred different stores in this area. Shalwar- kameej and frocks are made from these fabrics,” he informs while hauling the bales on the heads of market porters.

Latif Mia works as a porter for one of the markets where the shops mostly sell grey material. He came to Dhaka from Barisal and obtained this job on a contractual basis. “We get Tk 25 for carrying 1000 yards of cloth. I can carry a maximum of 500 yards in one trip. I send about Tk 4000 to 5000 home on a monthly basis after my expenditure here,” Latif states as he rests for a while before taking another bale of grey to a dyeing factory. Liton Mondol who works at a store that sells grey cloth, says that the unprocessed fabric can be made from cotton or silk threads and the price fluctuates with the price of thread. The grey cloth stores in the Islampur purchase their goods from mills in Madhobdi and Narshingdi, where they are weaved often with imported threads. Mahi Fabrics, a shop that only sells cotton chikan fabric, purchases and dyes its materials locally. Shopkeeper Mohammad Barkatullah says: “We purchase greys from shops in Islampur and then send the bales to factories in Gazipur with our designs. The designs are stitched on the cloths and returned to the shop for dyeing. Then we send the bales to Pakija Dyeing to be dyed into different colours. Once that is done we display the rolls at our showroom. Retailers from different districts of Bangladesh come to our shop, choose and buy their desired design and colour.” One of the major problems of Islampur is its unnerving traffic jam. “Nothing has been done to widen the road or improve communication to keep pace with the growth of business here,” says Dhali. He complains that the road is badly in need of repairs but no step has been taken. “We have employed community police who works alongside traffic police to control the heavy traffic on Islampur Road,” he says noting that even this step is not enough to handle the pressure of Eid shoppers.

Once a renowned shopping area for all sorts of consumer goods, Islampur now appeals only to fabric traders and a handful of consumers who dare to cross the sea of traffic and search through the nooks and corners for their desired fabrics. There are no markets exclusively selling a particular type of fabric, neither any written directions to help with the search. In spite of Islampur's inconvenience, customers do manage to find the finest cotton, silk, chiffon, georgette, brocade to adorn and facilitate life starting from the first blanket for wrapping a newborn to the shroud covering the dead. Traders and ordinary people who frequent the place somehow seem to know their way through the maze of colourful fabrics of different print and texture and miraculously, trading activity goes on uninterrupted at Islampur braving all kinds of odds.

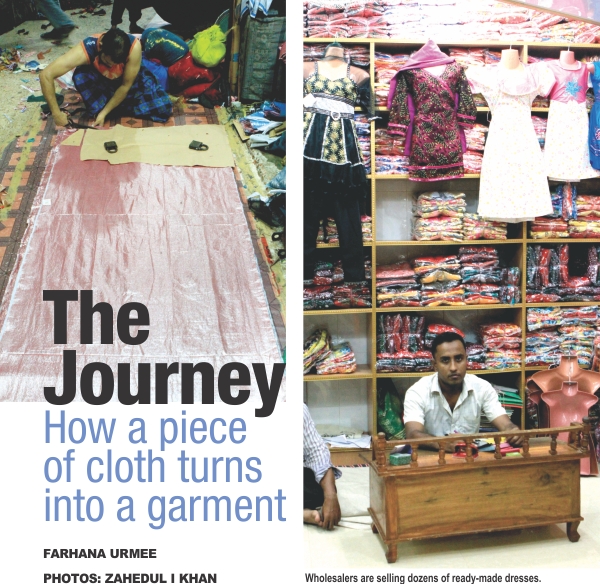

The little white dress with red borders hanging high at the shop attracts the customer passing by. Wahida, in her mid thirties, tries to get through the crowd to have a closer look at the dress which adorns the body of a mannequin. Standing in front of the shop she notices that dress has two other accessories-- a white hat and a red bag. The dress, with its comfortable fabric, modern design and patterned needle work, is the right one for her nine-year-old girl. It is the dress to buy which she has come all the way from the city's Chawk Bazaar to New market. The closer she moves towards the shop the clearer her idea becomes about the establishment-- it has a good collection of ready-made clothes for children and adults. Wahida gets to learn that the shop sells quality products at a reasonable price, and each dress is available in three colours and different sizes. Wahida assumes that she has chosen the right place to shop for her family as she has gone shopping on a limited budget, but the board hanging on the wall that says 'fixed price' is a little unwelcoming to her.

“I buy ready-made clothes because it is easy and cost effective and saves a lot of time before festivals; the high-price tag is disappointing though,” says Wahida. The shopkeeper, on the other hand, says that the price for a child's dress has gone up by 600-1000 taka as the production cost has also shot up. “It is impossible to sell clothes cheap as I have to spend a lot of money at every level”, says Biplab the proprietor of Shamabay clothes store. He is a retailer of ready-made garments in New Market and has to buy his products at a higher price these days. “I generally buy my products from the wholesale market around New Market. I mostly buy from the wholesaler of Chishtia Market and Ismail Mansion of Elephant Road,” he says adding that if he needs to buy products from faraway areas (like villages in the outskirts of the city) then he would have to further raise the price of the products to adjust the transport cost which is naturally imposed on the customers. Yet garments made from this area naturally cost higher than that of village-made ones. There are factories at Kamrangirchar which make children's clothes, stitched-unstitched three pieces, skirts, fatuas at lower costs as those factories get labour and space at a cheaper rate. “I buy products from both types of factories depending on the designs, cost and above all the demand of the product,” says Biplab. People coming to this market usually belong to the middle or lower middle class, so the final cost of the product is a big consideration. But the price hike of cotton and yarn has forced the traders to buy products from wholesalers at a price higher than ever before, fomenting a price hike for the customers. Customers often come and look at clothes but cannot afford them due to high prices. Regarding the amount of profit they make, Solayman who is the manager of the Khan & Sons matching Centre, New Market points to a number of reasons for which the ready-made clothes stores are not doing as well as expected this season. “It has been 54 years that our shop is selling clothes (ready-made and cloth piece) but it seems people are not buying clothes like they used to before,” says Solayman showing their daily register of sales. “It is true that the purchasing capability of people has increased; besides, it is also true that it has become harder to keep pace with the continuing price hike of the daily necessities and thus middle class people tend to cut their consumption of clothing”, says Solayman reasoning his declining sells.

Last year the flood in Pakistan and the Indian ban in cotton export gave a blow to the yarn market and made the price of yarn shoot up suddenly. From local traders, who buy cloth for factories, to retail buyers, who buy the finished product--everyone has been equally affected by the price hike. Again, the tax on imported fabrics is also affecting the local market of ready-made clothing, different clothes store owners say. Then again, once there were hardly three or four markets in the city but today if you travel from Mirpur to Dhanmondi you will get to see a number of shopping malls and departmental stores selling ready-made clothes on either side of the road. The increased number of places to buy clothes has helped to decrease the demand for ready-made clothes, think shop-owners of New Market. Retailers of ready-made clothes also point out to the tendency of the customers to buy Indian and Pakistani three-pieces rather than the local ones. He agrees that they often sell local products similarly made as foreign ones claiming them to be imported fabrics. “Even the whole-sellers claim a number of clothing to be made in neighbouring countries, and we also buy them knowing their fake origin”, says Solayman. A number of dresses are claimed to be made in India or Pakistan especially when it is a stitched three-piece and children's clothes. But the wholesalers say that they often try to copy the designs due to the huge demands for such products. Rafiqul Islam, proprietor of a wholesale shop of children's garments at Ismail Mansion, Elephant Road has his factory in the same market. He has 12 tailors working at his factory who make at least 12 dresses daily and a master tailor is working there to decide on the design, cut, colours of the dress. There are around 150 such factories in Ismail mansion and 150 other factories in neighbouring Chistia Market and Noor Mansion in Elephant Raod. Each factory on an average has 12-15 people, who include the master designer. Clients from city's markets, hawkers and shopkeepers across the country flock here to buy read-made dresses from the wholesale shops. “Primarily after designing a dress we send them to factories situated at city's Mohammadpur, Mirpur area for additional needle work, embroidery, accessorising them with beads/stones, Chumki (tinsel) work. A few factories send their products to villages in Kamrangirchar or Narshingdi for handwork, but machine sewed embroidery is cost effective as one regular machine can design 7-8 clothes at a time in five minutes. Finally, the finished product at the wholesale market is displayed for sale. Industry insiders say that they make clothes the whole year round and sell them in the season of festivals, mostly Eid and Pooja. A regular wholesaler can sell products amounting to Tk 10,000-15,000 daily round the year, but in season the sale become double. A ready-made garment, in its long journey, moves from one hand to another to get fine-tuned; travels from one place to another to be stitched and designed to find a place in the wardrobe of a retail buyer. Its final destination however remains the buyer, who stands at the end of the chain.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||||

Only Ahsan Manzil, the palace of Dhaka's Nawab, situated on the western side of Islampur validates Yakub's reminiscences. Being near the river, trade and commerce have always thrived in Islampur, which is named after Mughal Dhaka's founder, Nawab Islam Khan Chisti. The Islampur mosque constructed during his time still stands proof of the neighbourhood's importance 400 years ago. Nazir Shah in his book “Kingbadantir Dhaka” (The Myths of Dhaka) states that Islampur was originally the business centre for fruits and local elders still call the place Aampatti (Mango colony). He also mentions that the British had set up agencies to conduct wholesale cloth business here in 1773, during the Company era.

Only Ahsan Manzil, the palace of Dhaka's Nawab, situated on the western side of Islampur validates Yakub's reminiscences. Being near the river, trade and commerce have always thrived in Islampur, which is named after Mughal Dhaka's founder, Nawab Islam Khan Chisti. The Islampur mosque constructed during his time still stands proof of the neighbourhood's importance 400 years ago. Nazir Shah in his book “Kingbadantir Dhaka” (The Myths of Dhaka) states that Islampur was originally the business centre for fruits and local elders still call the place Aampatti (Mango colony). He also mentions that the British had set up agencies to conduct wholesale cloth business here in 1773, during the Company era. Many traders in Islampur import their merchandise directly from foreign countries. Abdul Majed of Amer Fabrics, involved in the cloth trade for 30 years, imports from India. “We go to India in places like New Market and Boro Bazar (located in Kolkata) and choose the fabrics. Then we write down a memo and give it to our supplier there. The supplier then brings the fabrics from India sometimes through Benapole and sometimes by air if there is an emergency,” he explains. Orders are usually placed four to five months before Eid and any other big festival. Retailers from New Market (Dhaka), Gausia (Dhaka), Chadni Chawk, Mirpur-11, Maghbazar, Urdu Road, Sadar Ghat and such other places come to buy renowned cotton from Indian manufacturers like Century and Arvind, he adds. “We give ten percent import tax to government. The import tax depends on the dollar amount of LC (letter of credit), on the quantity of the goods, the container size etc.,” Majed continues.

Many traders in Islampur import their merchandise directly from foreign countries. Abdul Majed of Amer Fabrics, involved in the cloth trade for 30 years, imports from India. “We go to India in places like New Market and Boro Bazar (located in Kolkata) and choose the fabrics. Then we write down a memo and give it to our supplier there. The supplier then brings the fabrics from India sometimes through Benapole and sometimes by air if there is an emergency,” he explains. Orders are usually placed four to five months before Eid and any other big festival. Retailers from New Market (Dhaka), Gausia (Dhaka), Chadni Chawk, Mirpur-11, Maghbazar, Urdu Road, Sadar Ghat and such other places come to buy renowned cotton from Indian manufacturers like Century and Arvind, he adds. “We give ten percent import tax to government. The import tax depends on the dollar amount of LC (letter of credit), on the quantity of the goods, the container size etc.,” Majed continues.