Cover Story

It's not Just About Hunger

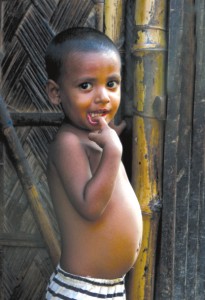

With a huge number of infants and young mothers suffering from various levels of malnutrition that makes them vulnerable to disease, the future of the nation is in danger of being severely stunted.

Farhana Urmee

photos: Zahedul I Khan

|

It is not just poverty that is the primary cause of malnutrition

in children. Lack of knowledge about nutrition has a big role

to play |

If you ask anyone in Bangladesh how are you, chances are that you will be greeted with a smile and the word bhalo, meaning 'well' will be the automatic reply. But the smile belies a grave reality; almost half of Bangladesh's people are malnourished and therefore far from being 'well'. They are in fact victims of a vicious cycle of hunger, poor nutrition, ill health and lower productivity.

Chandni, a mother of a five-month-old baby boy smiled and gave this predictable answer when asked how she and her baby were doing. Her appearance says otherwise. Painfully thin and pale with dark circles under her eyes she looks more like a teenager than the 20- years- old she claims to be. Her baby, also just skin and bones, can barely keep his head on her weak shoulders as he listlessly stares at nothing in particular. It is glaringly obvious that they are both under-nourished and possibly stunted.

The five-month-old boy is her second child, as the first one died eight days after birth. As far as Chadni was concerned her baby did not have any illness. “My neighbours say our first child died as it was not protected from evil spirits,” says an anguished Chandi.

Chandni, like many other young women, does not know that a malnourished woman who is underweight is most likely to give birth to underweight babies whose chances of a healthy life are cut short while they are in their mothers' womb. The problem is more severe in the case of teenaged mothers (a common phenomenon in rural Bangladesh) who suffer from lack of nutrition even before they are pregnant. For Chadni, the wife of a rickshaw- puller and living in a Beri Badh slum, not being healthy is quite normal. But it is not necessarily just poverty that is equated with malnutrition although there is a direct link between the two. Lack of knowledge regarding nutrition is also a major cause.

According to Chandni there is nothing wrong with her health or that of her baby's besides the occasional cold. Besides breastfeeding her baby, she gives him shuji (semolina) as a supplement to make sure his stomach is full. She says she does not have enough breastmilk to feed her child and elders in her family have suggested the shuji supplement.

According to nutrition experts worldwide, nourishing a child must be initiated right after birth through exclusive breast-feeding and that too within an hour of giving birth. Nutritionists vehemently discourage giving an infant less than six months old, any food other than breast milk; even water should not be given. Exclusive breast-feeding must be continued until six months after which a child must be given complementary food for proper growth. In absence of these two factors a child is likely to suffer from malnutrition for life and after reaching adulthood or before that (in case of teenage pregnancy), will pass the legacy of malnutrition to the next generation.

Though Bangladesh has a culture of breast-feeding, there are problems regarding lack of awareness over the right time to start nursing and complementing it with other digestible food. World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of a baby's birth. Forty-three percent of infants under six months of age in the country are exclusively breastfed only for two months. Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) (a UNICEF global strategy on child nutrition), also, highly recommends that infants should not be given any sort of liquid or semi-liquid food other than breast milk until six months. But more than half of breastfed children under six months receive water, juices, other milks or complementary food and 20 percent are receiving solid or semi-solid foods. IYCF practices suggest introducing complementary food for a child beside breast milk only when a child is six months old. This reduces the risk of malnutrition.

|

Lack of proper nutrition takes a heavy toll on children at every stage of their life. |

The IYCF practices recommend that breastfed children from 6-23 months should also be fed food from the three or more food groups. Less than half (44 percent) of breastfed children meet this recommendation. After being weaned from breastfeeding children should be fed milk or milk products, and food from four or more food groups. Only about one-third (36 percent) of non-breastfed Bangladeshi children receive milk or milk products, and 31 percent were fed food from four or more food groups. Over all, among all children aging 6-23 months, only 42 percent were fed according to all three IYCF recommendations, reveals Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey (BDHS) 2007.

The BDHS 2007 also measures children's nutritional status by comparing height and weight measurements against an international reference standard. According to the BDHS 2007, 43 percent of children under five are stunted or too short for their age. This indicates chronic malnutrition. Stunting is more common in rural areas (45 percent) than the urban areas (36 percent). Again, 17 percent of children are wasted (emaciated for their height) and 41 percent of children are underweight. Stunting is common in the poorest households, where more than half of children are too short for their age. In comparison, 26 percent of children are stunted in the wealthiest households.

Not only children, mothers too are severely malnourished. While the poor are the most vulnerable due to continuous hunger and poor nutrition even those who are better off are not well educated about nutrition and health of expectant mothers. Mili, a service holder, is six-months pregnant but she doesn't even know what her weight is or, more importantly, what it should be. Pale and thin, she seems constantly tired. When asked she seemed reluctant to talk about nutrition and her colleagues say she has little interest in food at a time when she should be eating for two.

|

Not only children, mothers too are malnourished. |

According to BDHS 2007 a high number of Bangladeshi women face nutritional challenges. Thirty percent of them are abnormally thin and 12 percent are moderately and severely thin. On the other end of spectrum, 12 percent of Bangladeshis are overweight or obese. “We cannot blame only poverty as the central reason of malnutrition. Proper nutrition has to be a big awareness issue,” says Dr Rukhsana Haider, the Chairperson of Training and Assistance for Health and Nutrition (THAN) Foundation. Malnutrition is becoming an epidemic due to people's ignorance about its causes, nature and consequences. Dr Rukhsana also observes that people should not only be told what to do in preventing malnutrition rather they must be explained how and why to prevent malnutrition in combating this silent killer. A vast number of underweight, stunted people is the consequence of undernourishment at certain times in life, say nutrition experts.

While explaining reasons behind malnutrition experts say, lack of food security and poverty is one of the main reasons of massive malnutrition in the country. The ever-increasing price of essentials is harshly affecting the lives of poor and lower income groups, making them helpless to meet their daily requirement for food. Moreover, due to lack of consciousness about balanced diets people from higher income groups do not eat properly either.

Frequent natural calamities often hinders high production of food in the country, which in turn affect food security and food prices.

The economic instability and price hike in various occasions throughout the year compel people earning hand to mouth cut meat, milk, fish, and some selected vegetables from their diet. UN Food and Agriculture Organisation also considers the instability of the price of essentials as being responsible for rising food insecurity. But increasing food security would not only be confined to growing paddy, rather the country must grow vegetables and other crops besides rice to meet it's nutrition needs, observe experts.

Bangladeshis from infants to adults all consume a high carbohydrate diet. According to Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2005, people in the country meet their daily need of calories mostly by rice, that is 72 to 79 percent. The statistics says a person takes 448 grams of rice while he or she is supposed to take 350 grams; 14 grams of pulses instead of 60 grams; 157 grams of vegetables instead of 200 grams.

|

According to the BDHS 2007, 43 percent of children under five are stunted or too short for their age. |

Dr Rukhsana Haidar, also the Senior Technical Advisor, Alive & Thrive defines the case of the health status of wealthy households in a different way, she calls obesity another kind of bad nutrition where a person does not enjoy sound health and the scenario is common mostly in urban, wealthy families. “Over nutrition or malnutrition; we all have a wrong attitude regarding nutrition. A child being fat or tall does not mean she or he is having a sound health and getting the proper nutrition as required,” she says, adding that people are suffering in the country from malnutrition from various age groups and across many social classes.

Sohel, a 22-year-old private car driver weighs only 48 kg, is five feet five and looks weak and frail. His slight body does not have the strength to push the car when it breaks down in the middle of the road.

Sohel's lack of vitality might go back about 22 years ago when he was not breastfed properly or given nutritious food in his growing years. Children who do not receive proper nutrition are less attentive in school and show poor performance, something that may continue throughout their adult lives if the problem is not addressed at the right time.

Nutritionist Faria Shabnam says stunting is a consequence of poor nourishment in childhood especially from birth to 24 months which is considered the most significant time of brain development. The conventional practice of delayed breastfeeding or delayed supplementary foods after six months still prevails in the country. Again lack of nutrition throughout the adolescence period also makes a person suffer malnutrition for life.

Sohel is not alone, from birth to 50 years or more, people are suffering from the consequences of poor nourishment. With undernourishment comes a weak immune system, making people dangerously vulnerable to disease leading to a poor quality of life and even premature death. Malnutrition is not only a reason for becoming stunted or underweight rather it also makes one's body vulnerable to a number of diseases like anemia, thalassemia, childhood-blindness and often it makes mortality rates higher both in child and adult mortality. An undernourished child after growing up as an adult becomes an easy target for the attacks of non-communicable diseases through out life, says Dr Mohammad Raisul Haque, programme manager, Health, Brac. Sadly most people are not even aware of the effect their chronic lack of nutrition has had on their lives.

|

A typical scene in urban slums includes scores of uncared

for, undernourished children. |

Dr Rukhsana adds that people must know there are certain periods of life when people remain most vulnerable to malnutrition. Such a time is childhood, especially between birth and two years. If a child is left out of getting nourished at this particular age, the losses are immeasurable and could never be compensated. Again, another significant period is adolescence when children are supposed to grow physically and mentally and become a fully developed human being. Improper nutrition might leave the adolescent physically and mentally affected forever. Adolescent girls who often get married at an early age give birth to underweight babies who grow up with high risks of being stunted in adulthood. Thus the cycle of malnutrition goes on. Dr Rukhsana also says that while there may be a marked improvement in life expectancy at birth if the child is not mentally or physically well and therefore less productive then this success does not have much meaning.

The problem of malnutrition is so acute that the country has gone down in the ranking in Global Hunger Index (GHI) than the previous years. Bangladesh takes the 68th position among 84 countries, which is worse than previous year's position of 67th among the same lot in the GHI. According to the Index in the 'alarming' situation of the country there is the highest prevalence of underweight children. The GHI is calculated for 84 developing countries on the basis of three leading indicators prevalence of child malnutrition, rate of child mortality and the proportion of people who are calorie deficient.

Talking on the consequences of undernourishment Jalaluddin Ahmed, Associate Director of Brac says that as a nation we are already facing the challenges of being undernourished. Citing examples from international games where Bangladeshi players take part he says, Bangladeshi athletes are not going too far in the international platform, as they are less fit than the other international athletes; it happens because of lack of awareness about nutrition and a general apathy towards the issue. Ahmed who's organisation is running a community based programme on awareness building and introducing IYCF practices among people says, the issue of nutrition must be taken with great interest by both the government, non-government organisations and civil society.

Proper nutrition at the right time is essential for healthy growth of children.

He also stresses on the economic outcome of a whole nation becoming undernourished day by day. Weak and undernourished people can never give their hundred percent in any job, and thus the productivity of a country decreases, which has a direct impact on GDP and GNP, he says.

Regarding the economic impact of malnutrition Dhaka University teacher MM Akash echoes the words of Ahmed. Besides poverty, lack of awareness is also responsible for severe nutrition. It is a country where forty percent people cannot meet their daily need of 2112 calories and on the other side there are people who are consuming excessive food much of which has very little nutritional value and have serious consequences on health.

Malnutrition is not only a reason for becoming stunted or underweight

rather it also makes one's body

vulnerable to a number of disease like anemia, thalassemia, childhood-blindness.

“This imbalance and these unhealthy practices are not letting people grow in a healthy way leaving different deficiencies in them. And how can a person who is not in the best of health be fully productive?” Akash asks.

opyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |