Religion

The Spirit of Ramadan Overseas

Fayza Haq

|

| Old town, Jerusalem. Photo: Christel Becker - Rau |

While the spirit of Ramadan is the same no matter where in the world it is observed, the difference in cultures can be observed in the diverse ways in which this month is commemorated. Angela Grunert, the Director of the Goethe Institut and Cynthia Farid, a barrister recently visiting from London, gave informative lectures at the Institut about the Muslim communities in Europe and the Middle East

Angela Grunert, recalling her experiences of Ramadan in Europe, Middle East and Sudan, gives us interesting insights of this Muslim month's traditions. She speaks of the third generation Turks and Arab youths -- coming back to the homes of their parents and grandparents -- to follow the traditional values of Ramadan.

Having spent seven years in the Middle East, and living in Berlin -- the melting point of cultures in Germany -- she has many interesting observations to recount. This she has put into a book, which involved ten years of labour. Photographs by Christel Becker - Rau illustrate her book, "Fasting with all its senses" (translated from "Ramdaan-- Fasten mit allen Sinnen").

Cynthia Farid, a young barrister, who has spent years in London, too has keen observations about the Muslim community's activities overseas.

They stressed on the true meaning of this month which is a time when one must hone one's strength of will and also internalise the concept of sharing with those who are in need. As an anthropologist, Grunert spoke of how Ramadan reflected positively on the challenges of transitional processes in Muslim societies.

Asked if the observance of Ramadan was similar in the Middle East and Sudan to that found elsewhere, Grunert says that the " framework" is similar -- the announcement of the beginning of the Ramadan -- and how it ends. There are strict preconditions, she says, as put in the "Quran" and the "Hadith", and culminating in "Eid". However, Grunert says, "There are cultural differences in the celebration. The rituals of difference places naturally reflect the culture of the country, along with the social and political aspects." She says that each country has its own cultural colouring in the observance of "Roza". In Asia, it has also to do with the culture that existed before Islam. This is the same in Arabic countries and in Africa.

|

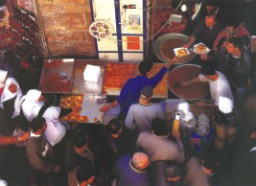

Bazaar. Photo: Christel Becker - Rau |

Berlin, which is Grunert's hometown is the melting pot of cultures, as many immigrants live there -- some of them all their lives there. The percentage of Arab and Turkish immigrants, she says, is 15%, she says." There you see the phenomenon of sticking together, as in many other European countries like Italy and France. They celebrate together, and spend the fasting periods together, in perfect harmony.

Grunert says, however, that life goes on, and one cannot expect that people in Germany to have time for prayers, putting aside the demands of their routine job and studies." While not every Muslim fasts the comraderie and joy of having iftar together is very much part of the communities' activities.

"The Turkish and Arabian youth have to adapt to the European lifestyle. Young Muslims have their own apartments, when they are 18 or so. But during Ramadan, they come together -- returning to the lifestyle of their parents and grandparents." says Grunert.

"During Ramadan' many Muslim families in Germany want to go back to their roots, and visit their families there. In this way, they enjoy the Eid festival in the traditional manner, and also carry out cultural musts like circumcision for the sons, when the boys reach the age of seven. When one goes back to Germany one returns to the "German" lifestyle! But everyone can't make a beeline for their home countries, like the refugees from Iran and Iraq, who have taken political asylum. But these individuals too yearn for their roots, and long to be with their families. The mosque is a place where they can meet other Muslims and exchange views and experiences. . The mosques are packed during Ramadan'-- during the 'Tarabi', at night," says Grunert.

Grunert she spent half of her life in the Middle East. This included Palestinian territories, Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

Talking about how Islam is observed in other countries Grunert says, "Religion there has a different role as it has here, in Bangladesh. What I saw in Sudan was very much controlled by the government. Religious and political situations, there, are somehow interlinked. The government there controls religious life, and vice versa. There, people think and discuss about the right way to do things.

Meanwhile, 'Darul Iftar' a state institution associated with Al Aqsa University in Egypt has become a centre for theological discussions explains Grunert. "Innumerable members of the public go there to consult their problems on any topic of life, and religious authorities." All branches of Islam can go there, she says, and quiz the authorities by asking questions like as to what point the senses should and can be actually checked and controlled.

Young ones come up with samples of difficulties during Ramadan, such as, "If a beautiful woman has on an irresistible perfume, how can one protect oneself from such a temptation?" Whenever you go there, Grunert says, one sees long queues of people with questioning minds, who seek answers to puzzles in their minds, says Grunert. Even questions of finance, such as, "How should I invest my money?" come up. Family issues are also discussed. "Ramadan is a month where people want answers to soul-searching and intriguing situations in life," says Grunert. Meanwhile, at that time, she says, newspapers are full of religious debates.

People in Egypt celebrate all night long, says Grunert -- and life is in full swing. The Egyptians love enjoying their Iftaar together, and this celebration is a joyous, public one -- after Taravi one goes out for amusement, as that's ok by the book. While cinemas are closed, but amusement is on in full swing in the cities, says Grunert. There are "Dervish" dances and music with drums, flutes and cymbals. Restaurants and shops are open all night. "When people tell you that they'll meet you at three o' clock they don't mean three in the afternoon, but in the morning," she says. Ramadan in Egypt is full of celebration and jubilation.

Ramadan in the Palestinian territories is not as jubilant because of the constant political tensions. Even in Ramadan the family can't always meet, says Grunert. They are not able to meet at the Al- Quds mosque (where the Prophet began his journey to heaven). Jerusalem is also important for the Jews. As it's under the control of Israel, one doesn't always have access to go there. This is a worldwide phenomenon and not one limited to Palestine. Here one can see Ramadan as a (political) tool. "The Hamas, before they got power in Gaza, invited the poor families to have 'Iftaar' and used it as a promotion campaign for their politics. At this time Arafat was alive. Even five star meals were served on the finest of china on these occasions. In the Middle East, often even the middle class try to serve Iftaar to the poor , as is the custom in many other Muslim countries. Many student groups collect money to sponsor the poor. Zakat and Fitra are taken seriously." says Grunert.

Cynthia Farid, who was in the UK for the last eight years, finishing her Bar, was shuttling back and forth between England and Bangladesh. Farid is a member of the "Institute of Hazrat Mohammed Alihussalam" in Banani, a research-based NGO in Dhaka, who look into various aspects of life, such as the ASEAN forum, and investigate into issues like refugees and violence. Farid has lived in Bangladesh till she was 18. Dwelling on the observance of Ramadan in the UK Farid says," Specifically in London, which is multicultural, you often don't miss home. There's a huge Bangladeshi and Middle Eastern population. So during Ramadan, generally, you see the unity of people coming together. It's not very different from here, except perhaps some of the rituals. They are more occupied with their daily work, but the general solidarity was definitely there."

Summing up the concept spiritual journey during Ramadan, on which she spoke at length at the Goethe Institut auditorium, Farid says, During Ramadan we practice self-restrain. The focus comes away from the rituals of food. It's like an inner journey in your self. You focus on prayers-- but not the ritualistic kind. The stress is on people coming together, and the idea of charity. This is like an inner transformation. It's not just starving yourself. It's minding your manners with members of the family, friends and basically, with other members of society. This minding of one's ways should extend throughout the year, and not just the 30 days of Ramadan."

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |