Remembrance

A Celebration of Courage

Razia Khan

|

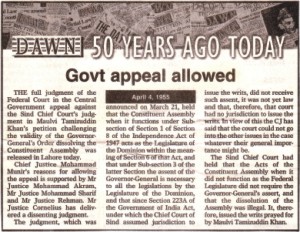

| Tamizuddin Khan, the then Acting President of Pakistan being greeted by Yusuf A. Ismail as he leaves for Rawalpindi at Cantonment Railway Station on September 15, 1962. |

Two obituaries in the London Times and New York Times were salvaged by my son Kaiser Tamiz Amin while doing library work in Boston. I lost the one in London Times which was short, unlike the long detailed obituary on my father in the New York Times. Hunting for the lost one in London I walked into the Marylebone public library -- where I found an affable young assistant who not only traced the obituary but declared with a smile, "I have found eleven other notices in the Times". He gave me copies of them at a cheap price. They covered his presence at the queen's coronation banquet and Princess Alexandria's wedding. I wondered how my father managed to skip the meat dishes served by gloved butlers -- as he only ate Kosher meat. At the Savoy, the hotel where he was staying he was given only fish and vegetables. This was the same man handcuffed by the British jailor Hogg for not saluting him, A Congressite and supporter of the Non-cooperation Movement, he had given up his lucrative legal practice at the behest of his mentor C R Das -- mayor of Calcutta a top Congress leader and a barrister with a princely practice (father's words in his memoirs The Test of Time).

Our family homestead along with paddy, jute and coriander fields were washed away by the angry Arial Khan, a branch of the river Padma, seven times. With rich yields from the land and leaseholds of two huge markets the family had been comfortable. But when my father started school my grandfather's resources were nil. He borrowed money from his rich Hindu friends the Kundus, to send my father to the Middle English School then to Scottish Church and Presidency Colleges in Calcutta. From Calcutta University father obtained a law degree. Armed with these he soon rose to be a successful lawyer. But as an ardent member of the Indian National Congress he gave up western clothes and embraced arrest -- coming out of jail after two years, penniless. Just as my ancestors were too proud to reclaim their land which had surfaced after the deluge -- by bowing to the 'low-cast' Hindu Zamindar, my father was too dignified to go to CR Das for a job. He fought elections with meagre, borrowed funds, defeated wealthy candidates and got elected to the Bengal Legislative Assembly. Joining the Bengal Cabinet twice as health and education minister, his last post was in the central assembly in Delhi from where he went to Karachi after partition. Our home and family disintegrated. Some went to Chittagong, some to Dhaka. Chosen Deputy Speaker, on Jinnah's death he became speaker of the National Assembly and President of the Constituent Assembly. Iskander Mirza, aided by Ayub Khan the C in C (Commander in Chief) dissolved the Parliament through a coup. They came to my father for support. What they got was grim resistance. Engaging the British lawyer D N Pritt father challenged the dissolution of the assembly. The New York Times and Herald Tribune ran the news in the headlines for a week.

Winning in the High Court, he lost in the Supreme Court where Justice Muneer launched his dubious doctrine of necessity. Father lived a few years more, winning the elections and being speaker of the national assembly. Before his death he was invited to the USA. As I turn the pages of old albums I see him on the steps of the US Supreme Court being received by Earl Warren the then Chief Justice; James Grant, then under secretary of state holding an umbrella over his head as he descended from the plane to the air field of a rainy Washington; the keys of that city being presented to him -- an intimate tete-a-tete with President Kennedy in the White House.

The Islamabad heat and hard work gave him pneumonia. He wanted to die in his own soil. He was flown in a military plane to CMH where he died. He was given full military honours. Buried in the national assembly premises his Spartan grave was in keeping with Louis Kahn's design in order to maintain the architectural harmony surrounding the parliament building.

There was always a wide gap between his and my political affiliations. He was a firm believer in Pakistan, giving up the Congress to join the Muslim League after the demise of C. R. Das who kept Hindus and Muslims united. Father did not live to see the disintegration of Pakistan, which was inevitable.

Before partition he had given up his Khan Bahadur title. District secretary of the congress in his home-town Faridpur, he attended the Nagpur Conference where 'little Indira was seen going round and round the chairs in the podium occupied by her grandpa Motilal and father Jaharlal Nehru'. (Test of Time).

I lost a valuable diary recording father's intimate sessions with Lord Attlee and meetings with Viscount Langley. I had left it in our London home from where it disappeared. Struggling hard to stand on his own feet, when family resources were meagre, he must have nursed a dream of elegance. The Calcutta home I grew up in was adjacent to the Victoria Memorial Hall. Blue lace curtains with matching sofas decked the reception room. An oval mahogany dining table on wheels -- was on which I was given lessons by my governess Mrs Eliot on how to handle instruments; she was given a well-furnished bedroom. A day and night nurse for my grandmother who had fractured her leg was provided. Two cooks one for local dishes, the other for European were kept busy in the kitchen. The office-room downstairs had typewriters which I tinkered with when no one was about. A small press was housed by another room from where he brought out two weeklies, The Medina and the Paegam. I lost a valuable diary recording father's intimate sessions with Lord Attlee and meetings with Viscount Langley. I had left it in our London home from where it disappeared. Struggling hard to stand on his own feet, when family resources were meagre, he must have nursed a dream of elegance. The Calcutta home I grew up in was adjacent to the Victoria Memorial Hall. Blue lace curtains with matching sofas decked the reception room. An oval mahogany dining table on wheels -- was on which I was given lessons by my governess Mrs Eliot on how to handle instruments; she was given a well-furnished bedroom. A day and night nurse for my grandmother who had fractured her leg was provided. Two cooks one for local dishes, the other for European were kept busy in the kitchen. The office-room downstairs had typewriters which I tinkered with when no one was about. A small press was housed by another room from where he brought out two weeklies, The Medina and the Paegam.

One winter morning, my old nanny whom my late mother had brought at a paltry price (human trade was still on!) was seen covered in father's expensive blanket. He must have thrown it over the shivering woman who slept on the dining room floor.

The first thing my father would do on reaching our Faridpur home by sea-plane was to don a lungi, take off his shirt and throw a huge fish-net over our pond teeming with all kinds of quality fish. Mrinal Sen, the brilliant film-director, once a close neighbour recalls seeing father bathing in this pond. He was impressed by my father's golden complexion. A Calcutta lawyer told me that as a young boy he had seen my father in the crowd gathered in Tagore's Jorasanko verandah on the day of the poet's death. He too was struck by the extremely handsome education minister. The declining sun made his face glow. His devotion to old friends was remarkable; Mr Tafseer, adviser Toufiq Imam's father lived and died in our house we felt that a close relative had departed. He was one of my father's closest pals.

Having never heard a harsh word from him I find myself ill equipped for the slights and insults life reserved for me. I never saw or heard him being rude to anyone.

During a convocation where I was to receive the certificate of the first position in BA Honours in English -- I saw some high-ups not treating him with courtesy. The VC of this varsity Dr Jenkins who had retired and left was education secretary when my father was education minister of the province. Had he been there this lack of courtesy would not have been possible. It broke my heart, I had an impulse to tear the certificate into pierces and run away from the scene. At that time he was not holding any high position. In Pakistan where city streets are named after him people never failed to honour him even when he was bereft of any official glory. For a long time people there were not aware of the atrocities committed by the Pak army in our land.

Father taught us never to use office stationary, not to waste electricity as the bills were paid by the government. Every time his cabinet stopped functioning, every piece of furniture was returned religiously.

His unfinished memoirs 'The Test of Time' unfortunately are full of unpardonable printing mistakes that should not be attributed to him. I have translated them into Bangla. They have been published by the Bangla Academy.

The Kundus, from whom my grandfather borrowed money to pay his son's college fees- have named a high school after my father in our native village. With government grants and help from the Tamizuddin Khan Trust, the school caters to the education of a large number of boys and girls.

Politics had created a wedge between father and us. Yet I remember him personally taking me to the dentist. After an attack of cerebral malaria I was taken by him to the doctor. This concern pleased me, small though I was. It was from the obituaries that I learnt about his Bengali novels now out of circulation; that he had done his BA Honors in English from Presidency College was also a late discovery.

I have never met anyone more reticent than him. He allowed me to be myself although my ways were often contrary to his ideals. I wallowed in leftist literature, acted on the stage. Curiously enough while I was performing the part of a woman barrister in Mr. Nurul Momen's 'The Law is An Ass', I saw my father sitting in the front row of the auditorium. Not a word was passed between us about this.

After my BA exams I look up English announcement for the radio. I had to open the transmission at 6 in the morning. He provided me a car every time I had to do this. I was rebellious, fiery and impulsive, traits which might have hurt him at times. A nonconformist, I always kept a statue of the Lord Buddha in my room. When I returned from England after a couple of years the statue was still there.

In British days ministers were not given official residences or cars. My father had a black Morris which he maintained himself. On becoming Speaker in Pakistan he used a government vehicle paying for the gasoline till he was able to buy a black Chevrolet during his first visit to the USA. This and land bought for building a house were sold during the Tamizuddin versus The Pakistan Government case.

We refrained from flying as my grandmother put an embargo on this. He begged her for permission to fly and finally in 1945 my grandma relented.

He had immaculate taste. On his visit to Paris he got us two shaded chiffon saris-mine was lime and apple green. He bought saris for my mother which she never got to wear, dying of cancer at the age of forty. A black georgette with floral embroidered border, a peach silk with dull gold border, a Benarasi with silver and blue waves all over the sari -- and a light chocolate tissue with golden polka dots -- decked in which my mother might have gone to Vice-regal parties. Instead, she was laid in a grave in Calcutta, wrapped in white cotton.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |