|

Reflections

War of Words

Syed Zain Al-mahmood

On my way to work the other day, I was startled by a snatch of song from the FM radio. A woman was singing in a husky voice. “Chele ta pichu chare na, it's bullshit! Jani na keno bujhe na, it's bullshit!”

I consider myself fairly broadminded, but the sound of a singer BS-ing on air struck me as pretty tasteless. I said as much to my friend Hamid. “Oh, it's all the rage these days,” he told me. “It's the dynamic new youth culture. You have to be rebellious. Haven't you seen all the new plays on TV? They have a new style of dialogue. It's the common touch. The djuice effect. Call it what you like.”

I am not a purist. I would be the first to acknowledge that culture is dynamic, and so is language. External influences have enriched our vocabulary and our customs for centuries. But there is something sad about the cavalier way in which we have been treating our language of late. Why should we accept without a whimper the tendency to insert the B-word or the F-word in the middle of a sentence?

It is not just profanity that is the problem. A whole host of treacherous new words have insinuated themselves into our speech. Many of them appear nonsensical or have taken on a bizarre new meaning. When a teenager says his exam was “Ura dhura” or “Jhakkas” you can't blame his parents for feeling lost. “Kothin” should mean difficult. But in the new lexicon it means just the opposite. “Kothin movie!” in the strange new tongue means “It's a darn good movie!”

|

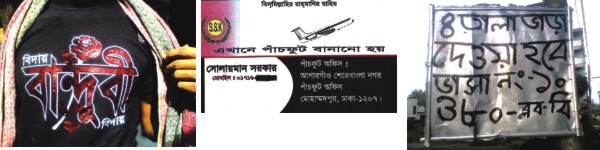

| Photo Credit: Sad But True |

A few days ago I overheard two young lads admiring a girl at a restaurant. “Meye ta hebby (heavy),” said one. Now, this could lead an untrained observer to think the lady in question was overweight and out of shape. But the boys' tone was appreciative. So I quickly concluded that in their world “hebby” meant slim and svelte. The question is, what shall we say when we really mean weighty or fat?

The same goes for “Josh” and “Jotil”. A lot of people might say this is nothing new. After all, we have always had dialects and slang. But what is new is the way these neologisms have been dragged into the public domain.

The “djuice culture” as Hamid put it, is being driven by, well, djuice. Short for digital juice, this is a youth based mobile phone plan from Telenor, the Norwegian telecom giant.

“Grameenphone put up huge djuice billboards all over the country with expressions like Kothin bhaab and Jotil Mood,” said Nafisa, a law student at Dhaka University. “That kicked off this trend, made it cool. Other mobile companies like Banglalink soon followed. They've literally spent millions to promote these expressions. It was something bold and young people responded to it.”

Nafisa's friend Irfan pointed to a new genre of drama serials by Mustafa Sarwar Faruqi and likeminded directors. “They have consciously moved away from so-called standard Bangla and use colloquial language and often dialects.”

Faruqi's supporters say he is trying to portray life as he sees it, but some viewers are worried about the effect such language may have. “It may be realistic, but I don't want my young son watching it,” said Abdul Alim, a father of two teenaged boys. “They hear street language on the street anyway. There was a time when you could learn correct pronunciation from television.”

Another force driving the new trend could be radio. FM radio has really taken off in recent times and young people can be seen walking around with earphones plugged in, engrossed in one of the many “request shows”. Radio Jockeys are often guilty of another kind of excess. I sometimes listen to FM radio when I'm stuck in traffic, and I've come to the conclusion that RJs are organically incapable of finishing a sentence in any one language. Why else would you say “ami tomake love kori” when you could say “ami tomake bhalobashi” or simply “I love you”?

“RJs are popular and some youngsters may see them as role models,” said Abdul Alim. “It's an artificial way of talking. No one really talks like that.”

The problem is, in some cases people seem to be forgetting the real meaning of words. “Apnar bhaggo ta justify korun (justify your luck!),” is a common cry from hawkers selling Red Crescent lotteries. He really means “jachai korun” (Try your luck). But does anyone care?

This is not just limited to people lacking an education. I have heard many executives referring to themselves as “employers of the company” when they mean employee. Last week, my neighbour floored me by referring to his car's radiator as “ready-water”. Well, it does make sense in a way it holds water and it must always be ready before you fire up the engine!

It seems almost as if we have given up trying to be correct in the way we use words. Sloppiness is becoming the norm. The news tickers on the TV channels regularly have misspelt words. Signs and billboards also have glaring mistakes that can be a constant source of entertainment.

Spelling mistakes are only part of this culture of sloppy speech. Exaggerations are common. Awesome used to be something that inspired awe, a mixture of wonder and dread. Now in the “djuice culture”, it just means “dude, that thing is cool.” I often see banners screaming “Moha pobitro Urus Shorif” at Sufi shrines. Super Holy Urus? It's almost as if mere “holy” is no longer holy enough.

Of course, a lot of people think it's all quite harmless. “They're just words,” said BRAC University student Sadi about the djuice expressions.

But words mean something. Words bring ideas alive, make new concepts familiar, and can change the way we see the world. Our use of words sets up apart from animals. Scientists like Noam Chomsky believe the ability to use words is genetic, and language evolved gradually as the more articulate humans passed on their genes.

One can see how that would work. When a saber-toothed tiger came calling, the better communicators could rally others and make good a plan of escape. They would later bask in the adoration of their peers. In contrast, the ones who merely screamed incoherently wouldn't get to first base. Loners, they would be easy prey for the Saber-tooth.

Today, words are just as important. When George W Bush used the words “War on Terror” it sent ripples around the world and set off a domino effect of bloodshed and prejudice. A word from the governor of the central bank could send the stock markets plunging. Words matter, and therefore we must be careful how we use them.

We must accept the fact that language is part of culture and that there is no reason for it to be more static than any other aspect of culture. The question is not whether we say things the same way as our grandparents, but whether we understand each other and whether the things we say offer enlightenment, entertainment, or emotion. The issue is not that language is changing but that the changes reflect other alterations in our society that are less than desirable. The problem is not that our grandparents would not understand us but that we may not understand each other.

In an era when we badly need to find common ground and shared experiences, there is critical need for a common platform. This is where a neutral standard Bangla -- or English for that matter -- becomes so important. If you say “Kothin mood” and I say “Abar Jigay!” and neither of us understand the other, then surely we have a problem?

The signs are not good. Between the “djuice effect” and the RJ phenomenon and the general decline in educational standards, it seems no one cares about the correct use of language any more. The battle appears to have been lost.

Not so, say 14,900 members of a web-based group called “Sad But True”. The group organises itself on Facebook and is dedicated to highlighting the (mis)use of language in the public domain. From spelling bloopers to grammatical howlers-- everything is pointed out and discussed. Surprisingly, the members are not linguistics experts but regular folk- 7 mostly students.

Group founder Safiun Nasir Tonmoy said he had started “Sad But True” in April 2008 with a few photographs of spelling blunders. “The group quickly became very popular, and people started to send their own pics. After a while Prothom Alo published some of our photos. We haven't looked back since.”

Tanim, a student of East West University, and Nigahe Murshida, a student of Sher-e-Bangla college help to administer the online community. “All credit goes to our contributors,” said Tanim. “Many of our contributors scour the country for examples of misuse of words.”

“We are building awareness,” commented Sajid Syed, a regular contributor. “We also have fun in the process. The popularity of Sad But True shows that people still care about using words properly.”

Many Battles may have been lost. But the war is not yet over.

.Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |