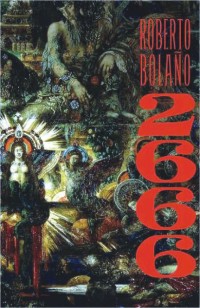

Most people aren't quite sure why they like Roberto Bolaño. His book "The Savage Detectives," published in English last year, was an unlikely success in the States, a sprawling, uneven novel about Mexican poets that ends with a visual joke. (Maybe it was all the sex?) Some reviewers tried weaving a web of other authors around him, hoping to catch something meaningful in it, or recounted the tinny resonances with Bolaño's own biography. Even in Latin America, where the Chilean writer has reached a nearly godlike status, plenty of critics and scholars flail about, scouring his books for clues and connections and really only agreeing on one thing: They like him. Bolaño's final novel, "2666," published roughly a year after his death in 2003 and just now released in English, is the prime example - maddening, inconclusive and very, very long; hideous in parts and beautiful in others; exerting a terrible power over the reader long after it's done.

Most people aren't quite sure why they like Roberto Bolaño. His book "The Savage Detectives," published in English last year, was an unlikely success in the States, a sprawling, uneven novel about Mexican poets that ends with a visual joke. (Maybe it was all the sex?) Some reviewers tried weaving a web of other authors around him, hoping to catch something meaningful in it, or recounted the tinny resonances with Bolaño's own biography. Even in Latin America, where the Chilean writer has reached a nearly godlike status, plenty of critics and scholars flail about, scouring his books for clues and connections and really only agreeing on one thing: They like him. Bolaño's final novel, "2666," published roughly a year after his death in 2003 and just now released in English, is the prime example - maddening, inconclusive and very, very long; hideous in parts and beautiful in others; exerting a terrible power over the reader long after it's done.

A synopsis of the novel's five parts - which Bolaño intended to be published as five separate books, and which are disparate enough to be - won't reveal much. So instead let's just say that the threads all cross where "The Savage Detectives" ended: in the severe Sonoran Desert in the north of Mexico, in a fictional border town called Santa Teresa, where hundreds of women who work at American maquiladoras are being raped and strangled. (The city is a stand-in for Juárez; murders like these happened there.) In one part, the deaths are told one by one and in detail, and even though you know from the outset they will never be solved, the long, grisly section drives along with the suspense of a detective thriller.

The novel is also a World War II epic, and a literary love triangle, and a chronicle of insanity, and the story of a washed-up African American journalist. Mostly, though, it is a novel about, and the product of, obsession. The characters in the first part are desperately searching for the reclusive writer Benno von Archimboldi, as others searched for Cesárea Tinajero in "The Savage Detectives." But it is the fact of being obsessed that matters. The muddled, incantatory monologues of the book's massive cast of characters, pathetically striving toward something they can't define - like that of the man who crossed the border to Arizona 345 times and each time was deported, or the Black Panther founder for whom, obtusely, "the danger is the sea" - this is the real reason to endure the loops and frustrating brinks of "2666."

The tragedy of the maquiladora women is self-evident; much more forceful is the emotion packed like gunpowder into these elliptical soliloquies. Each is brimming with a weird urgency and sadness - weird because the sadness is not in the content but in the telling, relying on dream signs more than actual events (like the German tanks that look "like the coffins of an extraterrestrial civilization"). In Camus' "The Stranger," Meursault must kill a man; here, a London bum's story of painting commemorative mugs contains just as much existential angst.

Echoing the resignation of colleagues who tried and failed to sum up the book, the Argentine novelist Rodrigo Fresán wrote: "It doesn't make much sense to read about '2666'; one must read '2666.' " And indeed, it would be futile to try to count up each of the book's thundering echoes, such as the maquiladora "like a melon-colored pyramid" suggesting all the ancestral violence of the Aztecs. As for the title, there are clues to its significance in other books, but trying to take apart Bolaño is like looking under the hood of a car to see what makes it go. The big cryptic number, like so much in the book, is a riddle without a right answer - ineffable, yet palpitating with meaning.

The Mexican writer Jorge Volpi has a story about a bad joke Bolaño told over and over at an event in Seville a few days before his death. A man walks up to a girl at a bar and says, "What's your name?" "Nuria." "Nuria, want to have sex with me?" "I thought you'd never ask." The young writers at the conference were captivated, Volpi says, sure that hidden there was "the secret of the world." And they weren't wrong.

This review first appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle.