| Cover Story

Dwelling and Dealing with History

Nader Rahman

When the dust finally settles after our historic buildings have been pulled down around the city, all we will have left will be pictures. The glorious past of a 400-year-old city seems destined to be captured and preserved through pictures alone. We are losing our heritage and pulling down our historic buildings even before we can take pictures of them. We are losing our heritage even faster than we can document it, but how does one deal with a problem few people are even aware of in the first place?

|

Stained glass windows speak of a different era. |

That is where architects Taimur and Humaira Islam of the Urban Study Group, come into the picture. They can proudly say that the two of them almost single-handedly brought Shakhari Bazaar back from extinction when they started a movement more than five years ago to save the historic market place. After a building collapsed there in 2004 the city authorities in an unusually proactive measure decided to survey the area and recommended that 91 out of the 157 buildings in Shakhari Bazaar be pulled down. It created an uproar and none were more vocal that Taimur and Humaira. They practically waged a war for the area to be deemed a historic site and argued that arbitrarily demolishing 91 buildings would not be in the best interests of anyone concerned. The market could become a viable tourist hotspot and more importantly there were houses and buildings located there that predated even the Mughals. Shakhari Bazaar and its buildings were part of the history of Dhaka, for that fact alone the buildings should not have been touched. The duo got their wish and managed to save many old and architecturally important buildings, but with one feather in their cap they were not about to rest on the laurels. Since then they have decided to tackle all of Old Dhaka, trying to search out old houses that need to be documented, restored and possibly saved from the clutches of developers.

|

Lal Kuthi |

Their work is lonely business except for the days when they arrange their weekly Heritage Walks which they started six months. They take groups of people out for a walk in the Old Town and along the way show them the great buildings of yester years along with some hidden gems, which they searched out by themselves. Ostensibly the walk is recreational, but it serves a variety of purposes. Firstly there is the odd chance that they may come across a 'new' old building, one which may have slipped through their search net. Aside from that it performs a sort of civic duty, informing groups of people about the history of Dhaka as well as showing them first hand that without our old buildings we would lose more than just a part of our history, but a part of our identity as well. Finally it shows the people living in the Old Town that the so called city slickers really do care about the area and it also shows them just a smidgen of what the tourist capacity may be if the houses were looked after and maintained well.

“The Old Town could be the biggest tourist attraction in Dhaka and could potentially being in an untold amount of money, but if the place is not looked after, if its historic buildings are not maintained then that will cease to be a possibility,” says Taimur. He points to Dholai Khal and then to the buildings across the street saying that all the old buildings there used to face the Khal. The open space and waterfront, made it a perfect place for a house and now those houses would face nothing but paved concrete. If the Khal could find its original location then he claims the place could be built up with street cafes and a sort of European openness could define what a wonderful tourist attraction it could be. It seems a good idea in practice but there is an overwhelming feeling that the pace of modern life has overtaken any such fanciful ideas. The khal has been filled up and the area is the better for it, what it needs in fact more than a street café is paved roads and sound drainage. The area that was once the heart of the city is now its dump, with quarter paved roads, horrendous sewerage facilities and a feeling of dirtiness that gets beneath one's skin. It could be argued that Dhaka City Corporation has not spent a single taka on the area in the past decade, they could argue differently but it simply means that they have not even stepped there of late.

The Heritage Walk takes one through Shutrapur and along the way a myriad of dilapidated houses are pointed out, they are ghosts of what they used to be. Many may call Taimur and Humaira dreamers for wanting to bring back the glory days of the old town, but one walk with them will change their minds. Their conversational chatter is a mixture of information and entertainment as they seemingly know the owners of every house and have more than a few stories to share.

|

| Architects Taimur and Humaira Islam |

They speak not only of saving individual houses, but also of area conservation, where small blocks of old houses could be saved to add a little more vibrancy to the area. The advantages of area conservation are simple to see, instead of a few scattered houses having regular segments of houses would greatly add to the over all ambience of the area. But generally when it comes to saving old houses some even older problems emerge, and they have to deal with keeping mind body and soul together. Most people would prefer to tear down their old houses and build an apartment complex which would provide 21st century living conditions and a steady income and truly one should not forget that those people have every right to do so. What can't be forgotten as well is that those very same houses which could be pulled down to make the dreams of a family come true are also a part of the rich heritage and history of Bangladesh. Even if the owners wish to tear them down, the government should step in and offer to purchase them at the market value and then convert them into museums or something along those lines.

But alas the fate of old buildings in Dhaka is one that cannot be avoided, the prime example is that of Rup Lal House. A stately mansion which once dominated the banks of Buriganga is now nothing more than a run down house which houses a spice market and serves as an army camp. To see it now it is to see an apparition, and yet it still dominates and takes one's breath away, what a sight it must have been in the days of yore.

In the end there is nothing left to be done by the civilian, the government is the party that should take up the cause of architecturally significant buildings around Dhaka, they could turn the old town into the tourist attraction, yet seemingly that will remain a pipe dream. Taimur and Humaira will continue to walk from road to road, trying to detail every last house, but for how long?

|

| Rup Lal House, now an occupied building. |

The best example of the history of the houses of the old town came when we arbitrarily stepped into a house that seemed to be built in Mughal style. We asked where the owner of the house was, hoping to gather more information on the property itself. He walked into the dimly lit foyer as I wondered if the room should even be called a foyer at all. What does one call a room that is essentially a foyer, but was built more than a hundred years before the word was even coined? Maybe there was a Mughal term for the word which as the years passed faded into obscurity, a footnote to a footnote. As I pondered the limitless knowledge of humans lost to history, I stood face to face with the owner, a professor of geography who could not tell me where he was, and he was standing in his own foyer. He was close to seventy years old and did not know the complete history of the house, when it was built and so on. All he knew was that it was his family house. There he stood in a house so old that he couldn't even guess its age and he had lived there his entire life as did his forefathers. Treasures like this could be lost forever.

Saving Dhaka's Soul

Elita Karim

|

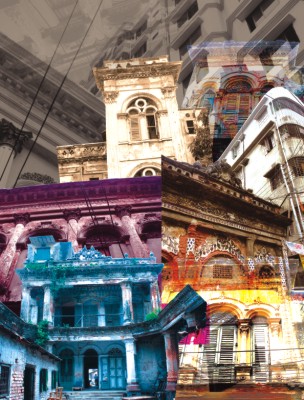

| Classic buildings with crumbling edifices dot the streets of the Old Town, silent reminders of a once noble past. |

Every morning right after Fazr prayers, 50-year-old Farzana climbs down the dark stairway at the back of the house and turns on the main water tap, linked to a hose upstairs, which fills up a 'house', similar to a bathtub. The family will use this water for the whole day. Of course there does come a time when the main water tap runs out of water altogether. That is when Farzana and the house help have to go down to a corner of the old courtyard and draw buckets of water from a water tap linked to a source outside the house. This has been the beginning of every morning for Farzana for the last 30 years or so, after she got married and shifted to Wari, Dhaka from Sylhet. “The house I live in still intrigues me,” she says. With huge, ancient doors and windows, the house dates back to pre-British periods. Wide verandas, high ceilings, massive kitchens, murals on the rooftop and much more, define excellent craftsmanship and architecture from the past.

|

The dilapidated mosaic walls of a Mosque. |

“There used to be a smaller balcony with the kitchen,” says Farzana. “We used it as a storeroom for a while, before it suddenly crumbled to pieces. Thankfully no one was hurt outside.” Farzana and the other members of the family also speak of the courtyard downstairs. “There was a well and long before I had come to this place, everyone would wash their clothes there,” she says. “When my father-in-law was alive, he had even put up a huge swing in the courtyard for the children. Besides flying kites on the rooftop, the swing was very popular with the children.” The courtyard Farzana speaks of now is no more as it is now home to at least thirty to fifty families belonging to government employees.

Hundreds of these ancient structures in Old Dhaka are slowly disintegrating. Moreover, instead of renovating these buildings or taking steps to preserve such grand architecture, policy makers have been thinking of taking down the structures. Some renovation was done in areas like Shutrapur, Farashganj, Shakhari Bazar, Tanti Bazar, where people still live in the 17th century structures. However, state negligence and apathy has made sure that the signs of the ancient beauty or architecture will disappear or be covered up by mindless renovation.

One of the major issues, in terms of these ancient buildings is ownership. According to Taimur Islam, an architect of Urban Study Group, an entity devoted to identifying heritage sites, even though many people have been living in the same structure for generations together, the fact is that they have been living on vested property. “During the 1947 partition, many properties were left when Hindus opted to move to the other side,” says Taimur Islam. “At one point these became government property and to date, families who live there are still living on the basis of lease contracts that are renewed every year.”

Cities around the world are always made famous because of the folklore and legends associated with the rivers in the cities. “It is extremely heartbreaking to see our Buriganga withering away as well,” says Taimur Islam. “This river identified and defined the city of Dhaka at one time. The river has slowly lost its charm and identity. We should make it a point to at least acquaint school children with the river. Otherwise we would not be able to help preserve our heritage.” Taimur speaks further of the ancient structures on the bank of this river which are

falling to pieces. People who live here do not realise the beautiful history that once was around them.

|

Left: Dholai Khal - made by destroying an important water body.

Right: Rup Lal house's massive courtyard. |

According to law, unless a structure is declared a heritage point by the Archaeological Department, the structure would not be maintained or looked after by the government. However, maintaining these structures is not as easy as it sounds. There are hundreds of such structures spread over, not only in the old part of Dhaka but also all over the country. Where will the money come from to preserve and conserve our heritage? Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed a Professor of the Department of Architecture from BUET puts forward his six-point-theory on preserving such buildings. According to him, firstly there should be the will to identify and preserve the ancient structures that we have in the city. Secondly, the ownership and the status of the structure should be defined clearly. Next, plans should be made with regard to what is to be done with the structure. Some of these structures are left to rot, lying around empty for years. Instead, they can be bought off and put to some kind of use. “Many structures can be used to make museums, schools and even hospitals if proper maintenance is provided,” he says. The hardest part would be to sanction enough funds for the plans to be carried out, which is the next step. “Funds are to be allocated accordingly to maintain these buildings,” he says. Dr. Ahmed adds that experts in this field should be consulted and made to supervise the plans. Preserving these ancient structures would be a difficult process without those with the appropriate technical know how. “Amongst the main methods, there are chemicals used for preservation,” says Dr. Ahmed. “A proper brick by brick investigation by experts is extremely necessary to bring these buildings back to life.” Lastly, Dr. Ahmed says that the actual operation is to be planned and carried out, along with the maintenance work.

Very recently, the government has finally decided to renovate and maintain these ancient structures that are spread all over the country. However, one still wonders how efficiently and diligently, not to mention how quickly, the government can handle such a huge task.

It was probably in the 1950s, when a worldwide attempt was made to adapt to international contemporary architecture. This also led to an urban removal policy which had wiped out many old cities in the world. “This was going on in Europe and the USA as well,” says Taimur Islam. “The plan was to install wider avenues, underground pathways and so on. Simultaneously, however, movements had begun in Europe and elsewhere to preserve the old heritage and stop the act of removing these cities. By the 70s, these movements had become extremely strong which stopped the removal acts completely. One can still see ancient Italian neighbourhoods in Boston and the Greek towns in Detroit. A conscious effort was made to preserve the heritage which was quite successful.”

The urban removal policy played a strong influence on many nations around the world, including ours. “The idea of removing the congested areas and establishing modern architecture appealed to everyone,” says Taimur. “The older part of the city was treated like a burden which the city needed to get rid off. Fortunately enough, the policy makers became busy with the extension of the city rather than demolishing the old part.”

The idea of Old Dhaka being a burden still exists within the minds of the people. We tend to forget the invaluable history of our own culture that resides in that part of the city-- the distinct dialect, food habits and lifestyle of a vibrant community. The people and the ancient structures of Old Dhaka is what gives this area its character and distinguishes itself from the rest of the city, adulterated by unplanned, unattractive so-called modern construction in the name of urbanisation. Preserving the architectural sites of Old Dhaka is the only way to remember the richness of this city's past.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |