|

Interview

A

Writer of the Known World

Winner

of 2004's Pulitzer prize for his novel 'The Known World',

African American writer, Edward P Jones was recently invited

by the USIS to come to Dhaka and give a few readings and meet

with people including school students, writers and journalists.

In an interview with SWM Jones shares his thoughts on his

motivation to write his first novel and what gets his creative

instincts going. Winner

of 2004's Pulitzer prize for his novel 'The Known World',

African American writer, Edward P Jones was recently invited

by the USIS to come to Dhaka and give a few readings and meet

with people including school students, writers and journalists.

In an interview with SWM Jones shares his thoughts on his

motivation to write his first novel and what gets his creative

instincts going.

AASHA MEHREEN AMIN

It's not

everyday that you get to talk to a Pulitzer Prize winner in

Dhaka. Especially one who doesn't really like to talk much.

But apart from the slight inconvenience of running out of

questions, listening to Edward P. Jones, is an intriguing

experience. Reserved and a man of few words, Jones is unapologetic

about his reluctance to explain his work. He writes because

he wants to, on what he feels like writing about. Which is

why he chose such an unusual story line for his second book

'The Known World' that won him the Pulitzer for 2004.

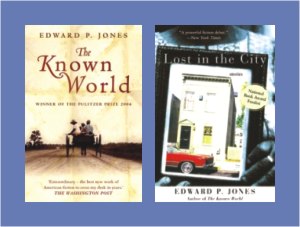

The backdrop

of the book is a plantation where slaves work and live out

their lives. But the slave-owners are black and the characters--

both black and white-- are complex with many shades of grey.

Jones's first book 'Lost in the City', a collection of short

stories was originally published in 1992 and short-listed

for the National Book Award.

It was

while in college that Jones heard about the fact that in the

1880s there were black slave owners and this bit of fascinating

history got him to visualise a full-scale novel. The story,

says Jones, centres on a 31 year-old black man Henry Townsend

who dies at the very beginning of the novel. He leaves his

widow a retinue of 31 black slaves and the story revolves

around them as well as other characters.

This includes

Henry's mentor William Robbins, a former white slave owner

who sold Henry's freedom to his parents. William sells a piece

of land to Henry along with a slave, Moses. When Henry dies

his wife is at a loss about running a plantation with thirty-one

slaves and begins to depend on Moses. Moses, on the other

hand, tries to get the slaves their freedom. Jones adds that

his book is about a myriad of characters and their complex

relationships with each other. There are rich blacks and poor

blacks, rich whites and poor whites, white people who are

sympathetic towards blacks and those who are blatantly racist,

American Indians and a light-skinned black who could pass

off as white but doesn't want to.

The writer

insists that there are no political messages in the novel

and that his writings are based purely on realism. "That

is what I aim for," says Jones. "They are simple

stories. I don't see why you have to be complex or dense to

tell a story; if you have an agenda then write essays, storytelling

is about human beings," he comments dryly.

Jones

does admit however, that American society is still a divided

one. "People of one class and race live in one place,

people of another class and race live in another." America

is a very complex society. It's not clear cut all the way

down…There are days when I get up and feel that I am

glad to be there and there are days when I feel 'why am I

here?'"

Jones's

own story is as engaging as his fiction. Born on October 5,

1950 and raised in Washington DC, by his mother, a dishwasher

from North Carolina who never went to school, Jones spent

most of his time reading books. Most of his early life was

spent in poverty. He studied English at Holy Cross and later

got his MFA from the University of Virginia. It was while

in college that he started writing seriously, coming up with

his prize-winning short story collection, Lost in the City.

Jones has regularly been published in the New Yorker Magazine.

Although

it took him about 10 years to complete 'The Known World' Jones

says that he read very little of the enormous amount of research

material he had collected. Thus Jones relied completely on

his imagination, a method that continues to be the main driving

force of his writing. He spent 19 years of his life summarising

business-articles for a magazine, a job that involved little

creativity but paid well enough for him to pursue his real

passion-- writing. Although

it took him about 10 years to complete 'The Known World' Jones

says that he read very little of the enormous amount of research

material he had collected. Thus Jones relied completely on

his imagination, a method that continues to be the main driving

force of his writing. He spent 19 years of his life summarising

business-articles for a magazine, a job that involved little

creativity but paid well enough for him to pursue his real

passion-- writing.

Jones

says that his ideas often come out of the blue. "You

might be buying eggs in the supermarket when you have an image

in your head of a woman in a corn field with blood on her

dress and holding a shotgun…It's not like you read the

headlines in the papers and say to yourself that you will

write about them." The writer adds that usually when

an idea for a story comes to his head he thinks out the whole

story line before he actually begins to put it on paper. But

the rest explains Jones is all hard work. Plus there is no

guarantee that the success of the first book will automatically

get transferred to the second one. "Every book has its

own life." His favourite writers include James Joyce

and Anton Chekov. Jones says that he enjoys watching movies

and is particularly fond of Satyajit Rays films.

Jones's

working regime includes getting up as early as 6:30 a.m. when

the 'sun is still fresh' as well as the mind. He says that

if he wakes late, say 9a.m then the whole day is wasted unless

of course he is at the end of a book or story in which case

he will go on until it is finished.

As a person

Jones is not much of a social butterfly and prefers to keep

to himself rather than go to a café to make intellectual

chitchat with writers over latte, as he puts it.

Jones

believes that for writers there is no end to learning. "It's

always a learning process," says the no-nonsense writer

who says that winning the Pulitzer was a big surprise: "I

never take myself too seriously."

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|