|

Cover

Story Cover

Story

Uchohla

Vanté

A Torchbearer among Indigenous People

Saymon

Zakaria

Translated by Mustafa Zaman

Uchohla

Vanté is a name loved and revered by the indigenous

people of Bangladesh. He has become a symbol among these people.

In Bandarban, his birthplace, 11 groups of indigenous people

now see him as a conveyer of peace and harmony. Vanté

was a man ready to start a career in the administration, but

a dramatic turn of events led his course to the path of Buddhism.

His educational background, religious training and wisdom

paved the way for him to position himself at the centre of

all the 'adibashis' living in his native land. However, it

is his recent activities that have made him a precursor of

peace and fraternity among all indigenous people.

At

one time, Vanté was a student in the Department of

Law, Dhaka University, then he went on to complete his degree

and was later appointed as a judge and magistrate by the public

service commission of the Government of Bangladesh. There

was also a creative side to him; he wrote and composed songs

in his own language -- Marma. But all this is now behind him.

Giving up his profession he has gone on to devote his life

to better the lives of his own people. In his effort to provide

education to the indigenous people, and to compensate for

the backwardness that blights them, he has established boarding

schools for orphans. His school is open to all indigenous

people. Chakma, Marma, Khumi, Bwam, Tanchonga, Chak, Pankho,

Mrwa and many other indigenous children are being given education

up to class ten. Uchohla Vanté now dreams of turning

his school into a college.

Vanté

believes that learning also includes knowing about one's own

culture. Which is why apart from establishing the school,

he has helped to introduce a course in Buddhist culture for

girls.

But

his most endearing project is the 'dhatu-jadee' -- a prayer

house for the Buddhist -- that has not only become a hub for

the Buddhists, but also a centre of attraction in the entire

Bandarban district. Vanté is a silent worker -- doing

things of his own accord while remaining in relative obscurity,

harbouring no ambition to get exposure. Although he has so

far been acclaimed for his work among the communities of Bandarban

and those who came to know about his achievements in foreign

countries, he is unknown to most Bangladeshis. But

his most endearing project is the 'dhatu-jadee' -- a prayer

house for the Buddhist -- that has not only become a hub for

the Buddhists, but also a centre of attraction in the entire

Bandarban district. Vanté is a silent worker -- doing

things of his own accord while remaining in relative obscurity,

harbouring no ambition to get exposure. Although he has so

far been acclaimed for his work among the communities of Bandarban

and those who came to know about his achievements in foreign

countries, he is unknown to most Bangladeshis.

Born in

the Bomang royal family, Vanté grew up loving the songs

and tunes of the people of Bandarban. His mother, Ong Mra

Ching and father Wu Hola Thoai Prue were ecstatic when their

son was born on December 22nd, 1955. More ecstatic was Vanté's

grandfather -- Bomang king Wu Kwa Ja San Chowdhury. The celebration

that followed the birth of the child has become part of the

folklore among his people. Vanté himself heard about

the revelry of his grand father celebrating his birth from

the local people.

Vanté

was a restive and mischievous child, but he was also very

shy. Music used to be his driving force and source of inspiration

most of his life. Even today, he quickly befriends anyone

with musical abilities or a deep liking towards music. Being

a Buddhist monk and a teacher he is trying to get over the

strong affinity he once felt with music. But in the religious

ceremonies organised by Vanté, he always makes sure

that songs are featured. Many of these songs are those that

he composed earlier in his life. Vanté

was a restive and mischievous child, but he was also very

shy. Music used to be his driving force and source of inspiration

most of his life. Even today, he quickly befriends anyone

with musical abilities or a deep liking towards music. Being

a Buddhist monk and a teacher he is trying to get over the

strong affinity he once felt with music. But in the religious

ceremonies organised by Vanté, he always makes sure

that songs are featured. Many of these songs are those that

he composed earlier in his life.

Why did

Vanté have to change his course of life and go back

to serve his own people leaving a promising career in government

service? It was his realisation that one of the consequences

of globalisation was the further marginalisation of indigenous

people. The 300 million indigenous people living in the world

today are at a crossroads. Not that their rich culture, language

and religious belief is eroding swiftly, but it certainly

is in the path to alteration. In the face of modernisation

in education, industry and agriculture in the twentieth century

and its impact on life, language and agriculture of many indigenous

groups of people, as well as their own tradition have been

deteriorating.

It

was in view of the decimation of cultural diversity, religious

beliefs, traditional lifestyles and agricultural norms that

spurred the United Nations (UN) to step in. It was in 1994

that the UN declared 'August 9' to be observed as "World

Indigenous People's Day". The day is observed not only

to protect the lifestyle of the indigenous people but also

to raise awareness across the globe about the rights of these

people. The issue of environmental protection is also bound-up

with the issue of treasuring indigenous lifestyles.

It

was in 1994 that in a general assembly of the UN 185 nations

in a joint declaration earmarked the next ten years as "World

Indigenous People Decade." The slogan that they came

up with made an effort to integrate them with the rest of

the world, it read "Indigenous people: partnership in

action." It

was in 1994 that in a general assembly of the UN 185 nations

in a joint declaration earmarked the next ten years as "World

Indigenous People Decade." The slogan that they came

up with made an effort to integrate them with the rest of

the world, it read "Indigenous people: partnership in

action."

In

Bangladesh, most indigenous groups are concentrated in the

coastal areas of the south-western region. The hilly district

-- Chattagong Hill Tracts -- is home to most number of communities.

In the

north-western and north-eastern region too, there are groups

of indigenous people struggling to continue with their own

lifestyle. There are more than thirty indigenous groups of

people living in Bangladesh. However, considering their number,

they are the minorities even among the minorities of this

land.

With these

struggling small communities, material pursuit takes a backseat.

For them, life is synonymous with living in harmony with nature.

In Bandarban, Uchohla Vanté is making an all-out effort

to provide an impetus to the pristine form of living.

The

Early Years The

Early Years

Vanté started school at age six and found kindergarten

to be quite a chore ending up being the 17th on the merit

list. He says, "After that terrible start, I never stood

anything other than first." However, his life at school

was not as smooth as it was suppose to be. If he had never

received flogging for not having to do his homework, he had

to endure it for his restlessness. But the same child displayed

diffidence while in a crowd. It was when he was in class nine

and ten that his coyness started to give away. At that age,

he began playing the guitar. The tunes he picked up and used

to give his voice to were the popular songs of his time.

"Rail

lainer oyi bastite," (in that slum near the railway lines),

"Orey Saleka, Orey Maleka," these are the sort of

tunes he tried to master. "Alongside playing the guitar,

I had a knack for playing the mandolin," stresses Vanté.

As an heir to the royal family, he not only had the chance

to immerse himself in music, he also had the opportunity to

opt for higher studies. "Rail

lainer oyi bastite," (in that slum near the railway lines),

"Orey Saleka, Orey Maleka," these are the sort of

tunes he tried to master. "Alongside playing the guitar,

I had a knack for playing the mandolin," stresses Vanté.

As an heir to the royal family, he not only had the chance

to immerse himself in music, he also had the opportunity to

opt for higher studies.

Vanté

was all set to go to college after he had successfully graduated

from school; at that stage he was ready to embrace all the

general characteristics of a conscious citizen of his country.

But his path was destined to lead him to a different destination.

After all, he was born among a people and into a family that

gave him a distinct sense of identity based on traditional

culture and values. The oral history that he grew up hearing

shaped his consciousness.

Life

at College, enlivened by Music

After passing SSC in 1978 in science from Bandarban, he was

planning to go to study at a college in Chittagong proper.

By then a college was established in Bandarban, and that resulted

in a change of plans. "I thought 'being a native of Bandarban,

if I did not enrol into that new college, who will'?"

One

interesting feature of that new-found college was that all

classes took place in the evening. "There was no fixed

teaching staff who would work only for the college",

says Vanté. "Many of the teachers were officers

working for government offices, and most were bankers. And

they used to spend the evening teaching at the college." One

interesting feature of that new-found college was that all

classes took place in the evening. "There was no fixed

teaching staff who would work only for the college",

says Vanté. "Many of the teachers were officers

working for government offices, and most were bankers. And

they used to spend the evening teaching at the college."

All classes

were conducted in the faint light of kerosene lamps. For this

the college earned an epithet -- "Lampo College. As classes

got postponed in the absence of teachers, Vanté had

his opportunity to strum his guitar and sing. He fondly remembers

his days spent in a daze, playing music. He mastered his guitar

craft during the lulls when classes got postponed. He used

to write songs alongside stories and poems. However, it was

during his college life that he began to roam around to collect

the local tunes.

He hopped

from one hill to the other, visiting the local villages to

pick up the traditional tunes of the people. The words that

he wrote used to accompany the tunes he picked up from the

locality. His songs were a hit with his own community and

continue to be popular even today. One of his songs titled

"Shangraima," became popular in 1975, and it still

remains the most-sung title of the festival that is also called

"Shangraima", that marks the end of the year.

Venturing

into the World of Law Venturing

into the World of Law

Vanté has a theory about his predilection for studying

law. He says, "I decided to study law as all the influential

leaders from Gandhi to Qaed-e-Azam were men with a grounding

in law." Although Vanté grew up showing promise

in the cultural sphere, he was accepted as a leader among

his people.

However,

for two consecutive years in his native Bandarban, Vanté

studied science and "to study law you need to have a

background in arts." By the time he decided on switching

the subject two years had already elapsed. "As classes

in science section were irregular I decided to opt for arts.

But, I had only three months left before sitting for exam.

I left for Chittagong and made the best use of the short time

before the HSC exam," Vanté recalls.

Once he

entered Dhaka University, he was, as usual, embroiled in cultural

activities. From there he even went on to audition for the

national TV and radio, where he became a regular. His recorded

songs are still aired, though he has long since ceased to

record any new ones.

But culture

for him not only revolved around songs, soirees and recordings.

Vanté was active, during his study, in making the indigenous

people aware of their rights and their identity. It was in

his university years that he established the Royal Cultural

Group, Welfare Organisation of Marma Students, tribal Aboriginal

Welfare Organisation, Bangladesh Marma Buddist Association.

1982

was a seminal year for Vanté, for he was faced with

a predicament of an philosophical nature which changed his

life forever. He was simply forced to recast his ideas about

life. As his loving sister Yee Yee Prue died in 1982 at the

age of nine, the whole community blamed it on a bad omen.

He made a resolve to emancipate his people from ignorance

and superstition. By that time, he had completed his Masters

in Law and was appointed a judge and magistrate after successfully

passing the BCS exam. 1982

was a seminal year for Vanté, for he was faced with

a predicament of an philosophical nature which changed his

life forever. He was simply forced to recast his ideas about

life. As his loving sister Yee Yee Prue died in 1982 at the

age of nine, the whole community blamed it on a bad omen.

He made a resolve to emancipate his people from ignorance

and superstition. By that time, he had completed his Masters

in Law and was appointed a judge and magistrate after successfully

passing the BCS exam.

"During

my student years, I didn't miss one function in the campus.

Lucky Akhand was the cultural Secretary and Shakila Zafar,

Shubhro Dev were the ones who were with us in our musical

pursuits.

But the

same Vanté, during his first appointment as a judge,

was forced to carve out a different life. "I could not

mingle with people. My job was made difficult by people badgering

me for favours, some even offered bribes so it was better

not to mix with a lot of people," Vanté recalls.

The domain

of the court and law seemed like a different hemisphere to

Vanté. A man who was used to sharing a joke with the

next person had to assume the role of a serious, important

person. The job seemed unsuitable to him. It was after his

sister's death that he realised he was wasting time operating

on a limited turf, serving a limited group of men. He strongly

felt the need to make himself useful to a vast community.

He decided to seek assistance from Buddhism, as for all the

indigenous people, faith is neatly bound up with everyday

life. An uncle of Vanté who first suggested that he

travel to Burma "where there still exists this schooling

based on teaching by the Masters to the disciple." Vanté

decided to leave for Myanmar.

Finding

His Mentor Finding

His Mentor

Once in Burma, Vanté was to meet a Mahathero -- a monk

of the highest order. The Mahathero recognised the sparks

of enthusiasm in Vanté, and asked, "There are

things that are prohibited, will you be able to sustain..."

Vanté simply wanted to know these don'ts, and once

the rules were laid down, Vanté was a man who took

them to heart. But the rest was a test of his patience. The

Mahathero he met only referred him to a Master whose description

Mahathero provided, but Vanté still had to find him.

The next

few days were spent frantically searching for the aforesaid

Master. Finally, Vanté tracked him down at a place

on the outskirts of Rangoon. But, once he encountered the

man who he thought would be his future teacher, Vanté

was told, "How can I teach you, I am engaged in poultry

farming, which is the cultivation of life. So, I am not at

all sanctified now. You would not learn anything from a man

like me. There is a friend who visits me, you can receive

knowledge from him."

As a third

man approached them, the chicken farmer pointed at Vanté

and said to him, "Here is a man from Bangladesh, who

has come here to receive your teaching." Uchola Vanté

had found his Master -- and since then his life has taken

an altogether different course.

The

Orphanage for Boys The

Orphanage for Boys

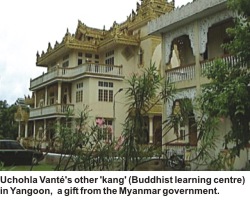

"Kang" is the place where orphans and boys

from poor hovels receive education. Classes start from seven-thirty

in the morning. Vanté established the kang

in 2001. He runs it with the help of eight other teachers,

although Vanté admits that he cannot afford to pay

them very well. His kang is open to all indigenous people.

"There are Chakmas, Marmas, Khumis, Khians and Tanchongos

and more, I teach them all here. And alongside teaching they

receive everything from clothes, medical treatments, stationery

that they need in school and even toothpaste and soaps,"

says Vanté.

Students

come from far off hills -- so far off that once the parents

drop them off, it is difficult for them to visit the children

frequently. "Most of the parents live hand to mouth.

They simply cannot afford to skip their work and come to see

their children. If they do, they would have to go on an empty

stomach that day," Vanté says shedding light on

the harsh reality the hill people face on a daily basis.

Besides,

parents put their trust on Vanté. They know that at

kang their children would be in taken proper care

of alongside receiving education.

"I

could've turned Kang into a college by now if I had financial

support. But I still dream of that future when it will be

a college. It's just that I don't want to take any help from

the NGOs, as then you must act according to their prescription,

each favour comes with a package of conditions. I receive

personal donations for my kang and that's enough

for this institution to survive," Vanté voices

his confidence. "I

could've turned Kang into a college by now if I had financial

support. But I still dream of that future when it will be

a college. It's just that I don't want to take any help from

the NGOs, as then you must act according to their prescription,

each favour comes with a package of conditions. I receive

personal donations for my kang and that's enough

for this institution to survive," Vanté voices

his confidence.

The

present enrolment at kang stands at 130. And to provide

them with three meals a day, 80 to 90 kg rice is cooked on

a daily basis. "Where will we get the money to spend

on rice? My disciples' contribution stand at 500 sacks (of

rice), and it is enough to feed us all for one whole year,"

says Vanté. The local disciples contribute from as

small an amount as Taka 10 to Taka 100, and as Vanté

puts it, "They are enough to keep us going.”

For young

women, there is the "Buddhist Meshali Cultural Training

Course." Vanté himself teaches the course. From

25 to 50 girls receive this training in each term, and few

are even given the opportunity to go abroad for further study.

At present, three girls are in Myanmar receiving further training.

While

teaching Vanté has also become interested in the "Quantum

Method" that teaches how to control emotion. His inquiry

led him to such lengths that he even wrote a book on this

subject, which is titled "Bidarshan Darpon."

As his

disciples keep him away from the corporeal tasks, for they

are zealously religious, Vanté is carving out a new

path to enlightenment. New in a sense that amidst all the

theological activities, he brings in the respite of music.

His is a practise that not only places the religious with

the musical, but also tries a modernist approach in reaching

the spiritual goals. Still today, he cannot resist the temptation

to get his hands on the harmonium. There were occasions when

he was criticised for his passion or sitting with the harmonium

trying to sing the sermons of Buddha. Vanté doesn't

consider it an aberration, as he believes that music is also

a way for humans to attain emancipation.

Vanté

on the Question of Language Vanté

on the Question of Language

Uchola Vanté has successfully united the adibashis

of Bandarban. It is his belief that the local languages --

Marma, Chakma, Boruna, Tochonga, Chak and Mrwa be learnt with

equal care. "We are learning to speak Bangla, we don't

have much trouble even learning English, but it is our own

language that is on the verge of disappearance," laments

Vanté.

"In

the past, during the British rule, we could travel to Burma

(now Myanmar) to get our hands on books on the languages we

speak," Vanté says. He quickly adds, "As

we are unable to bring back books published in Myanmar, our

languages are dying." And to press home his point he

continues," Our children cannot even speak the Marma

language properly. They speak a Marma that has 20 to 25 per

cent Bangla in it. Even the addresses at public meetings are

not Marma, it is a weird mixture of Marma, Bangla and English."

Vanté's

contention is that a Marma child should be allowed to learn

Marma at the primary level in school. "My plea is to

the government. The last time my attempt almost became successful.

When the government was ready to ok the plan for introducing

Marma text books for Marmas, a government change pigeonholed

the project. Bad luck for us, we were even through with printing

of the books," recalls Vanté. He cites the UN

declaration that made February 21 the International Mother

Language day, and argues, "If Marmas are allowed to study

in their own language only then would the February 21 be meaningful

in Bangladesh as Mother Language Day."

The

Golden Temple or Jadee The

Golden Temple or Jadee

The word "jadee" derives from Sanskrit

“chetee", it means "the subjects

of adulation alternative to Buddha."

In the jadee that Vanté built lies the ashes

of Buddha. With its magnificant build and the gilded golden

facade, the jatee is a landmark in Bandarban.

"For

the poor people it is beyond their means to travel far and

go to see a jadee. It is this thought that drove

me in my endeavour to build one," Vonté exclaims.

It was

in 1994 that he sent a letter of request to the Myanmar government

asking for 'ashes' of Buddha. His request was granted and

when in 2000 the temple was complete, it was a dream come

true for Vanté, as he himself designed the structure.

"There are several different designs the Myanmar temples

adhere to, it was after appraising all that I came up with

one of my own," says Vanté. After forming his

design he showed it to an engineer, who worked with it to

orient it according to proper structural measurement. "The

original structure is mine, I mean, stolen from a lot of other

temples," he says with a smile.

Now,

the temple is the epicentre of all the religious rites of

the Buddhists. The local Bhuddhists throng to the temple on

the Buddha Purnima, Kathin Chibor Daan, Dharmachakra Day,

Abhidharma Dibosh and the Tainchhang Dhaja Day. It is not

only the religious rites that are observed, the last day of

the year -- the Shangraima is one huge festival that the temple

plays host to. It is during festivals that Vonté's

songs still find a sympathetic audience among the indigenous

people. Now,

the temple is the epicentre of all the religious rites of

the Buddhists. The local Bhuddhists throng to the temple on

the Buddha Purnima, Kathin Chibor Daan, Dharmachakra Day,

Abhidharma Dibosh and the Tainchhang Dhaja Day. It is not

only the religious rites that are observed, the last day of

the year -- the Shangraima is one huge festival that the temple

plays host to. It is during festivals that Vonté's

songs still find a sympathetic audience among the indigenous

people.

How does

a singer, song-writer and a judge take an oath of living a

life of a monk? This is a question that Vanté is often

faced with. "People are curious about this. One day a

Hindu gentleman asked me, 'What is the matter Vanté?,'

I said look up in your own shastro or scripture,

it says: If you are given a million lives, try and become

a shadhu (saint) in one," Vanté explains.

He

has faith in the supreme designs of life and he goes on to

explain the saying in the Hindu scripture, "In millions

of lives that you are awarded with, your effort would be to

build up on the virtuous acts ion by ion.

Therefore, I say, that my transformation was sudden.” He

has faith in the supreme designs of life and he goes on to

explain the saying in the Hindu scripture, "In millions

of lives that you are awarded with, your effort would be to

build up on the virtuous acts ion by ion.

Therefore, I say, that my transformation was sudden.”

After

embracing teachings of Buddhism Vanté has come closer

to his people and now has the chance to contribute to their

wellbeing. In their spiritual crisis as well as in worldly

struggles, they have one man beside them, one man they can

rely on -- Uchohla Vanté.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|