Law Opinion

The Village Court

A neglected but potential rural justice forum

Zahidul Islam Biswas

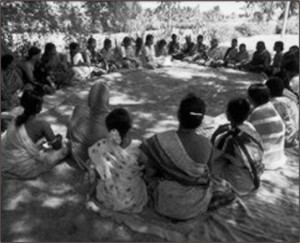

VILLAGE level traditional juridical mechanism named 'shalish' is active in rural Bangladesh from time immemorial. An informal justice mechanism, Shalish is: 'basically a practice of gathering village elders and concerned parties, exclusively male, for the resolution of local disputes. Sometimes Chairmen and elite members of the Union Parishad are invited to sit through the proceedings. Shalish has no fixed dimension and its size and structure depend entirely on the nature and gravity of the problem at hand (Sumaiya Khair: 2001).'

While the above description may suggest that a shalish is a 'calm deliberation, with the parties patiently putting forth their perspectives and impartial facilitators soberly sorting through the issues' but actual shalish is of peculiar character. Stephen Gloub describes his impression flowing from the observations of over a dozen shalish sessions during the 1990s as follows:

'The actual shalish is often a loud and passionate event in which disputants, relatives, (shalish panel) members and even uninvited community members congregate to express their thoughts and feelings. Additional observers adults and children alike gather in the room's doorway and outside. More than one exchange of opinions may occur simultaneously. Calm discussions explode into bursts of shouting and even laughter or tears. All of this typically takes place in a crowded school room or other public space, sweltering most of the year, often with the noise of other community activities filtering in from outside. The number of participants and observers may range from a few dozen to well over one hundred (Stephen Gloub: 2003).'

However, shalish mechanism as a justice forum has some specific characteristics. It is a completely informal mechanism which has no specie procedure to follow. The adjudicators (shalishkar) of a shalish do not have any legal authority, but they get social authority from their seniority, wisdom, economic and religious status or by way of village politics. For delivering justice, shalish mechanism uses no specific law but the notion of justice emanated from religious guidance and sense of social wellbeing.

A shalish may involve voluntary submission to arbitration (which, in this context, involves the parties agreeing to submit to the judgment of the shalish panel), or mediation (in which the panel helps the disputants to try to devise a settlement themselves) or a blend of the two. 'Shalish addresses almost all type of disputes- civil, criminal or family. These often involve gender and family issues, such as violence against women whether within or outside marriage, inheritance, dowry, polygamy, divorce, maintenance for a wife and children, or a combination of such issues. Other foci include land conflicts as well as other property disputes (Stephen Gloub: 2003).

The purpose of Shalish is to dispose off different type of local disputes locally, speedily and amicably without resorting to formal expensive and lengthy court procedures. While it is undeniable that shalish has been successful 'in some measure at providing acceptable judgments and solutions (Fazlul Haq: 1998)', it is also a bare truth that this purpose of the shalish mechanism has been frustrated time and again due to various socio-economic and religious grounds.

In the absence of specified law, process and accountability, the forum has been a vehicle for imposing subjective notion of justice by the socially, economically or religiously powerful people. While socially and economically powerful people have got this forum as a platform for enforcing their dominance over disadvantaged portion of the society, the religious leaders have used this forum as an instrument for practicing their religious dogmas.

These malpractices or biases in the shalish system are broadly categorized as class-based and gender-based. One the one hand, the powerful portion of the society have supported their class against disadvantaged group, on the other hand the patriarchal society, sometimes with the assistance of the religious leaders, has uphold their patriarchal notion of justice. The statement gets support from the following paragraphs.

'Although shalish members have the option of engaging in either mediation or arbitration to reach a solution, most commonly choose arbitration. This method involves unilateral decisions made by officiating members, whereas mediation engages opposing parties in reaching solutions of mutual satisfaction…Although the decisions are not always fair and equitable, they tend to carry a great weight within the community because they are issued by well-known and powerful villagers...'

Sometimes solutions are arbitrary and imposed on reluctant disputants by powerful village or community members. Such “solutions” are based less on civil or other law than on subjective judgments designed to ensure the continuity of their leadership, to strengthen their relational alliances, or to uphold the perceived cultural norms and biases. The shalish also is susceptible to manipulation by corrupt touts and local musclemen who may be hired to guide the pace and direction of he process by intimidation. Furthermore, because the traditional shalish is composed exclusively of male members, women are particularly vulnerable to extreme judgments and harsh penalties (Sumaiya Khair: 2002).'

Against this backdrop, Village Court are created in 1976 with the objectives that poor village shall get easy access to justice without any cost, they can be freed from accepting unwanted decision given by the dominant or elite classes of village in the name of justice and disputant parties can be able to solve their problems by themselves with a little or necessary assistance from these dispute resolution forums.

It is mentionable that the Village Courts are statutory courts and are composed of with local government (Union Parishad) representatives (as community leaders) and members from disputant parties. But these courts are legally required to follow informal procedure of trial or dispute settlement, meaning thereby that the application of Code of Civil Procedure, Code of Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act has been barred. Also is barred the appointment of lawyers. The underlying argument is that the disputant parties will be able to discuss all their problems without any reservation or hesitation and can take an amicable and justifiable decision. However, decisions of these courts are as binding as those of any other formal courts of the country. In a word, both these forums are examples of accommodation of formal courts and traditional knowledge and wisdom.

Noticeably, though a long time has passed after introducing this village justice mechanism, the government of the country has not undertaken any research to assess the performance of the judicial institution, or to assess whether the institution is being able to fulfil the aims they were introduced to meet. However, some non-government organizations and some private individuals in the recent years have conducted some small scale researches on the village courts that show that the performance of the arbitration council and village courts is very poor and unsatisfactory.

Though this Union Parishad administered dispute resolution forum does 'not impose the fatwas and harsh punishments that the extreme forms of the traditional practice entail', often 'the reality of village courts does not differ substantially from that presented by the traditional process.' A number of sources suggest that the dynamic and the membership of the Village Courts often resemble the traditional form of shalish in terms of being either biased or ineffective at providing justice for the disadvantaged, including women (Stephen Gloub: 3003).

In the like manner, a Bangladesh Ministry of Women's and Children's Affairs paper quotes the head of a local social service NGO as saying that dispute settlement by Union Parishad members 'ignore the rights of (sexually abused) women and girls and either dismiss the case or award them money as compensation.' As an Asia Foundation report suggests: 'UP Chairmen, who are often overwhelmed with many disparate responsibilities and little governmental support, tend to view family disputes and other violations of law as low priorities. Many UP Chairmen and members are also ill-informed in the law, and some are reportedly corrupt and politically motivated, causing them to act with prejudice (Sumaiya Khair: 2002).'

In this way, various research literatures reveal that the Village Court, a state-led rural justice institution, has not succeeded to be adequately reliable judicial forum for vulnerable rural communities. Still traditional shalish are rampant, perpetuating the regimes of impoverishment. Hopefully, some NGOs have been supporting local dispute resolution as an alternative forum of state-led and traditional forums of rural justice. These NGOs supported programmes run by knowledgeable law officers and well-prepared documents have been seeing the light of success gradually. But these NGOs legal aid activities cover hardly 1% of around 70,000 Bangladeshi villages. According to a UNDP report, two third of the disputes do not enter the formal court process. So still two-third disputes are disposed off in traditional Shalish, Village Courts, Arbitration Council or they remain unsettled.

When these traditional shalish system as well as semi-formal judicial bodies like village courts and arbitration councils are failing to give substantive justice, the socio-economic conditions of majority of the Bangladesh village people and lengthy process of the formal courts are preventing them to move to the formal judicial system.

The outcome is that vast majority of the people of the country is still out side the net of 'access' to justice, let alone access to 'justice'. However, a simple reading of the Village Court Ordinance implies that almost all major aspects of an effective justice system have been addressed in the law. A proper implementation of the law could improve the state of 'access' to justice dramatically. But that did not happen. Then why the mechanism is not working effectively is a question to be researched. Though there have been some researches on it, I think those researches are not adequate to address the issue properly. It is time government undertook an in-depth study, not a fly-in-fly-out study, to dig out the problems of the rural justice system and address those problems without delay.

The writer, an advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, is currently with the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, JNU, New Delhi. He can be reached at: [email protected].