Inside

|

Let's Hear it for the Girl Sharmeen Murshid shines a light on the shocking treatment of girl children in Bangladesh and around the world

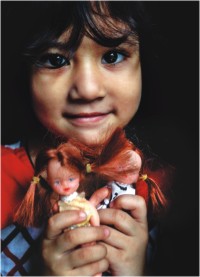

With every death of an unborn girl child, nature trembles as it fights to maintain harmony on the planet. The ethics of patriarchy, capitalism, and consumption as the post-modern social ethos appears like a monster that consumes everything -- even itself. With the death of every girl child, we die, nature dies. With the unnatural preference for boys, there is already an imbalance of the genders in Bangladesh, India, and China. With more boys than girls new socio-psychological problems will come to be -- worse than we can imagine. The ugliest form of patriarchy is murder of the unborn girls and the ugliest form of capitalism is the modern day slavery of women and children -- trafficked for sex. In an integrated and interdependent world of nations, problems do not belong to isolated countries -- they belong to us all. We affect each other and therefore cannot turn away from one another. There is a global socio-economic value system that creates a conducive environment for violence on the girl child. There is a market and there is a seller and a buyer for the product. To bring humanity to modern market mechanisms, only a global approach will work; only a global approach will meaningfully contain violence against the girl child. The story of a little girl A frail little child, she began going to school. Rose was a bright and intelligent girl. She loved school. Then one day that too stopped because the boys in the neighbourhood would tease her. And father had to cut costs to make ends meet, and, of course, Rose's education would be the first logical cost to cut. Rose was sad and silent. The poor parents soon decided to marry the child off as if that would solve all the problems. That, too, was not easy. The parents of the unemployed boy, Karim, asked for dowry so that he could start a business. Where would they get the dowry money? The father took a loan from a village money lender at an exorbitant rate of interest -- that, too, only half the amount -- the rest to be paid later. The child was married. Soon Karim demanded the rest of the money. He began to abuse and beat Rose. She knew her father could not pay and she could not ask him. Abused and battered, one day Karim and his family threw her out. Karim would be married again for a good price. Rose returned to her parents' home, with her a little baby. She would be taunted. She would live as a recluse afraid to eat, afraid to speak, and afraid to ask. A woman without a husband is a woman with no identity. Rose thinks: where she should go? What should she do, a burden to the family with no skill and no education. "Here lies your husband's home and there lies your father's, where is your home, dear, where is your home?" so goes an old Bangladeshi village saying.

The girl child begins her life with rejection and no space in society. Her family relieves its burden by getting her married off. In-laws throw her out for money. No place with father and no place with husband, she is out on the street. Out on the road, society, too, gives her no place, no work, no respect. Without education or skills, she is ill equipped to tackle the challenges she faces. Treated as a "street walker," the girl needs unimaginable strength and determination to make a life for herself in a judgmental society that misses no chance to humiliate her. The girl child is born in pain, violence, neglect, poor health, and humiliation. Does Rose become a street walker like many of her peers? Or does she commit suicide? No, she fights. She joined a group of young people in her village who decided to do something to protect the human rights of the poor, the children, the women and the marginalised. They decided to resist violence against woman and the poor. A team of five girls and five boys from poor peasant families formed into village action research groups (gono gobeshona dal). They saved money to build a little capital to help one another during need. They began challenging dowry marriages, child marriages. They worked to put every girl child into school and succeeded, with 100% enrolment from every household through a house-to-house motivation of parents. These bigger children started voluntary coaching centres for children from ultra poor homes and brought down the drop out rate. The village youths have found new meaning in life. So has Rose. The small village youth earned the respect of the elders, the local government. The local government body consults them and calls them to their meetings, taking their opinion in identifying the needy in distributing resources to poor families. A new generation of leaders, of resource persons, gender sensitive and caring, proudly begins to take responsibility for themselves, for the poor and their human rights. This gono gobeshona dal hold regular consultative meetings with villagers in gram shobha (village assembly), identifying problems, sharing information, finding solutions, and putting these into action. Violence against the girl child Society expects this. In fact, praises her for her patience. The more she endures, the more she is glorified -- a clever way to sustain patriarchy and imbibe values of patriarchy in a woman, until she learns to value a son more, a son's mother more, and before she knows it she practices the same injustice to her daughter and daughter-in-law as she has endured, convinced this to be right. This is the worst form of violence, quietly eating away your dignity, your objectivity, and your sense of humanity -- the violence most difficult to tackle. Of course there is the more obvious violence with its physical manifestations. While the poor child in general is subject to various forms of social exploitation, for the girl child it is more so. A nation of young Bangladesh is one of the few countries in the world where the number of girls (49%) is less than boys (51%) and this difference is a result of the social neglect of the girl child who at birth is born stronger than the boy but eventually becomes weaker and more malnourished due to her lesser social value. One third of all children are underweight. 70% of 5-year-olds suffer from malnutrition and 1 out of 7 die before they reach the age of 5. Some of the major causes of death are water borne diseases, respiratory deaths, and malnutrition. Aids awareness is poor and 50% of those affected are women. There is next to no sex education. Girls of 15 years and above are 40% more illiterate than boys. Enrolment in schools at all levels is lower than boys, and the gap grows at higher levels of education. The drop out rate for girls is also higher than boys. To cut family costs the girl's education is hit first: "since the boy will take care of the family in the future, the family prefers to invest in his education." However, the trend is girls are doing better in education than boys even at higher levels. In a land of 140 million people, 12% of the total labour force is child labour, aged between 5 and 14. In 1991 it was 4.1 million, in 1996 it was 6.6 million; girls in labour force was 1.6 to 2.7 million. More and more children are thrown into the labour market with increased impoverishment, reckless urbanisation, natural disasters, and river erosion. Child labour is part of the family economy to make do. There are 16 registered prostitution centres. A study shows 4% of prostitutes are under 18 years; 50% of migrating prostitutes are girls between 15 and 20; 25% of girls in this profession experience first sex at the age of 10. According to Unicef, 40% are under 16 years. There are 300,000 sex workers in India from Bangladesh.

Trafficking of women and children is the ugliest form of violence and abuse. It is estimated that 400 children and girls are trafficked out every month to Pakistan, the Middle East, and even to Europe. In the last 10 years 500,000 women and children have crossed the borders and were forced into prostitution. This is modern day slave trade. Child marriage is a violence that socially persists and at times is linked to trafficking. About 5% of children between 10 and 14 and 48% between 15 and 19 years of age are given to marriage according to ILO. According to Unicef, 50% are pregnant by 18 years and 58% become mothers by 19 years. Not in Bangladesh alone Child marriage is also a multi-country phenomenon. About 48% of teenagers in the world are married, despite laws setting age limits. It is worst in South Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Child prostitution is rapidly increasing worldwide. It is estimated that nearly 1 million girls are brought under prostitution every year: 100,000 in United States alone; in Hong Kong and Taiwan 40,000. About 30% teenagers (15 to 19) are forced into prostitution. Of all children deprived of education, two thirds are girls. In developing countries, girls are considered a burden and destroying the fetus has become a frightening practice of violence against the unborn girl. In some Mumbai clinics 95% of female fetuses are aborted. This is acquiring epidemic proportions in India and China. Some thoughts for the future The girl-boy distinction in early childhood leads to a cycle of prejudice and violence -- where the boy is the perpetrator and the girl is the victim. There are no winners here, and both boy and girl can lose their sensitivity and humanity -- even before they are grown up and able to understand and take responsibility for the violence that becomes a normal part of their lives. So much is being done, and yet, so little has been achieved. On the one hand, at the micro level there is no alternative to "un"-learning processes at childhood; education for all; family values of equality and respect. For these to work, poverty has to be controlled and women/girls have equally go to be part of the productive process (which in fact it is, though often unrecognised).

The garments industry is a good example which brought a small revolution in the lives of poor women who could respectfully be an earning member of the family. But it is far from enough. Children, who are part of the poor family's economy, have been squeezed out of garment factories as per ILO requirements. But where have the children, the little girls, landed -- on the street to be abused and exploited in a far worse manner than in the factory. From the frying pan into the fire. Ground realities demand that laws should be sensitive to realities and not just be "idealistic" and hazardous for the child. The lesser evil is my recommendation here. Keep the child in the factory, make the employer pay for his or her education and for his or her meal, and let the child learn life skills to survive and help his or her family with dignity. This should be the law. This is what all factories must be obliged to do for child workers. At the macro level, there must be greater global collaboration to stop the new slave trade -- child trafficking. There must be concerted vigilance over selling and buying points. Child prostitution must be banned and severely punished in the demand countries. In the name of free market and capitalism, such evil practice cannot be permitted anywhere in the world. If there is no buyer there eventually will be no seller. At each point of this trade, nations must unite, both at the level of governments and at the level of civil society, and robustly address this international social disease. Sharmeen Murshid, a sociologist, is the CEO Brotee. |

Amirul Rajiv

Amirul Rajiv