|

Interview

Shooting Women

In an exclusive interview, writer-filmmaker Alexis Krasilovsky talks to Rahad Abir about her work and the philosophy that guides her life

You said in a session at the 10th Dhaka International Film Festival that Satyajit Ray's cameraman Subrata Mitra made you interested in becoming a cameraperson. How did that happen?

I grew up in the New York suburbs, where like so many other families, our father left early in the morning for the city, and when we kids went off to school, my mother was left in a big, empty house. As I approached adolescence, I understood her loneliness and isolation, even though I was set on going my own separate way. Satyajit Ray's “Charulata” is the film that made me understand grown women's loneliness: those long, haunting dolly shots of cinematographer Subrata Mitra's, following the wife through the hallways of her empty house allowed me to see the world through her eyes. Meeting Mitra, who had come to New York for a cinematographer's conference, inspired me to

Alexis Krasilovsky |

want to become a cinematographer myself, to further explore this kind of vision.

In your times it was really challenging to think about building a film career as a woman. How did you make that possible?

I didn't think of it as becoming a woman filmmaker. There were so few women filmmakers, it would have been almost impossible! I thought of it as becoming a filmmaker. However, when I did encounter sexism, I had the Women's Liberation Movement behind me. I organised with other women; I chaired one of the first international women's film festivals at the American Film Institute Theater at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC in 1975, and later joined groups like Behind the Lens, An Association of Professional Camerawomen, Cinewomen and Women in Film.

I was 19 when I started directing. Because I didn't know it was almost impossible for a woman to launch a film career in 1971, it actually was possible. The film I made in 1971, "End of the Art World", starring Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, screened in the Museum of Modern Art, has recently been re-released on DVD.

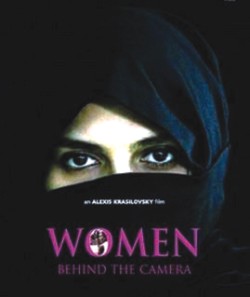

Your recent and most well acclaimed film is “Women Behind the Camera.” This documentary is based on your book, which bears the same title. How did you get the idea of writing this book?

I didn't have the courage or tenacity to persevere as a camerawoman, but I admired those camerawomen who did-using the unions and networks, if necessary, to get work. One cameraman wanted me to swim naked in the ocean with him after a shoot which had entailed walking up and down sand dunes with heavy metal cases of film equipment. I was so proud of myself, proving that I could do this gruelling job, and for what? The manager at one of the cinematographeres' unions that I joined only had one question for me, and it had nothing to do with cameras: he wanted to know how tall I was. The camerawomen whom I met in Los Angeles as a member of Behind the Lens, An Association of Professional Camerawomen had much more fascinating stories to tell. By then I had already directed several documentaries, and recognised the importance of documenting the perseverance and visions of these talented pioneer camerawomen.

What interesting things did you find while researching the book and later making the film, “Women Behind the Camera”?

It was actually easier for women to work behind the camera in the very early years of cinema, before the Hollywood Studio System took over. Alice Guy-Blaché is credited in "The Moving Picture World" of 1912 as having operated the camera as early as 1895 or 1896. So it's even more disheartening that, of the 250 top-grossing Hollywood films last year, only 2 per cent were shot by women. At first I was surprised to find camerawomen in France and India such as Vijayalakshmi, who already has 20 feature films to her credit as Director of Photography, whose film industries have been so much more supportive than Hollywood. I'm now editing a second book that goes more into depth about camerawomen's experiences in Australia, Austria, Canada, England, France, India, Iran, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, Senegal, South Korea and other countries.

Despite discriminatory hiring practices, isolation and sexual harassment, many camerawomen today have successfully transcended, or, increasingly, have never perceived themselves as victims, but rather see themselves as dynamic, strong, committed professionals. As Sue Gibson, BSC, the new President of the British Society of Cinematographers has stated, the main issues for female Directors of Photography today have to do with lighting, composition, and translating the director's vision.

My first book focused more on professionalism than women's visions. But, while traveling in Ahmedabad to see Gandhi's ashram, I soon found myself introduced to the camerawomen of Video SEWA (Self-Employed Women's Association), a group which helped the rural villages of Gujarat survive an earthquake that had killed 20,000 as well as a severe drought by picking up cameras and influencing policy makers. That's when I realised that this project was much bigger than just me, and that in making “Women Behind the Camera,” I was serving as a facilitator across boundaries for women and filmmakers to connect globally. This is also true of our second book-in-progress, Women Behind the Camera: World Conversations with Camerawomen, and our website, www.womenbehindthecamera.com.

After many years of documenting the aspirations and obstacles, satisfactions and conflicts, failures and successes of camerawomen throughout the world, I have grown to appreciate the resonance of their stories. Global connectedness has become my obsession, so much so that I have started another global documentary, this time about the world's hunger crisis. Shooting began in Bangladesh last week.

We have seen that in Iran there have grown some brilliant women filmmakers. What is the picture of women cinematographers/filmmakers now in Hollywood?

One cannot talk about women filmmakers in Hollywood today without mentioning  organisations like the Alliance of Women Directors and Women in Film. These organisations have empowered hundreds of women filmmakers. I don't know if there are many women filmmakers here in Hollywood who can rival the sheer brilliance of the Makhmalbaf sisters. I recently saw the younger Makhmalbaf sister's “Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame” at the Flying Broom International Women's Film Festival in Ankara, Turkey, and consider it a perfect film. Certainly the cinematography of Ellen Kuras, ASC on “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” has a visual brilliance, and Kasi Lemons' “Eve's Bayou” masterfully portrayed a young girl's perspective, especially given the beautiful cinematography of Amy Vincent, ASC on that film. What's especially notable in Hollywood now is the wide range of individual visions of female directors in Hollywood, from Kathryn Bigelow's blockbuster action films to the independent visions of young women filmmakers empowered by the Digital Revolution, who are often able to convey a lot more in their films that's personal and relevant to social issues. organisations like the Alliance of Women Directors and Women in Film. These organisations have empowered hundreds of women filmmakers. I don't know if there are many women filmmakers here in Hollywood who can rival the sheer brilliance of the Makhmalbaf sisters. I recently saw the younger Makhmalbaf sister's “Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame” at the Flying Broom International Women's Film Festival in Ankara, Turkey, and consider it a perfect film. Certainly the cinematography of Ellen Kuras, ASC on “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” has a visual brilliance, and Kasi Lemons' “Eve's Bayou” masterfully portrayed a young girl's perspective, especially given the beautiful cinematography of Amy Vincent, ASC on that film. What's especially notable in Hollywood now is the wide range of individual visions of female directors in Hollywood, from Kathryn Bigelow's blockbuster action films to the independent visions of young women filmmakers empowered by the Digital Revolution, who are often able to convey a lot more in their films that's personal and relevant to social issues.

“Today, almost anybody can be a filmmaker,” you said. Could you say something about the digital revolution?

To be an independent filmmaker no longer necessarily requires that you be independently wealthy and have a trust fund that you can spend on 35mm film. However, the competition has gone up proportionately to the falling costs of film production. Over 10,000 films competed for slots at the Sundance Film Festival last year. Some filmmakers are able to make do without costly publicity campaigns that are usually needed to launch films theatrically, and still have their films reach audiences through word of mouth and the Internet. But just because anybody can be a filmmaker, doesn't mean that anybody can be a good filmmaker. As Samira Makhmalbaf has stated, it takes artistry, much more than technical competency, to be a filmmaker in today's world, where the technology is so easy and inexpensive.

Sometimes independent filmmakers face a kind of censorship. What do you think about that?

Egypt, Iran, Libya, Syria and Saudi Arabia are some of the countries that do not have free, uncensored media, freedom of artistic expression or free entry of foreign arts or press. Wherever the arts are stifled and creative exchanges prohibited, the soul of a nation suffers. I hope that this will not be the case for the future of Bangladesh, which has already suffered so much physically and emotionally. One of the most important challenges of independent filmmaking is to document the world's suffering and to bring that suffering to the attention of the world. This is the spiritual challenge of independent filmmakers.

Who are your favourite cinematographers? Have you been influenced by their works in your filming?

I am greatly inspired by the cinematography of Boris Kaufman (“L'Atalante”), James Wong Howe, Jaroslav Kucera (“Daisies”), Subrata Mitra (“Pather Panchali”) and Gabriel Figueroa (“Los Olvidados”), but perhaps their influence on me will have to wait for full expression until I am able to make feature-length narrative films.

What do you want to reveal through your films?

I want to address women's voicelessness and the chasms of silence, to portray life's injustices, sorrows, and redemptions, and to reveal the possibility of change.

Alexis Krasilovsky was born and raised in New York. Krasilovsky was the first to include the film techniques of zooming and dissolving in her motion picture hologram, “Created and Consumed by Light” (1975). As head of her own production company, Rafael Film, Krasilovsky has written, directed and produced numerous films and videos, including “End of the Art World” (1971), “Blood” (1975), “Exile” (1984) and “What Memphis Needs” (1991). Her film “Women Behind the Camera” won the Best Documentary Feature award at the Female Eye Film Festival in Toronto, Canada, and her shorter version, entitled “Shooting Women,” recently won the Best International Documentary award at the WOW (Women of the World) Film Festival in Sydney, Australia. Alexis Krasilovsky is currently a professor in the Department of Cinema and Television Arts at California State University Northridge, teaching film and screenwriting as well as continuing to make her own movies.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |

|