|

Cover

Story

Beyond

Stage Performance Beyond

Stage Performance

Shahnaz

Parveen

Most

Adivasi festivals showcase cultural heritage in the brightest

of colours. The fanfare that marks such events always overshadows

the real life experiences and travails Adivasis put up with

on a daily basis. The recent Adivasi festival made an attempt

to bring into view issues that have a strong bearing on the

existence of the Adivasis. SWM takes a closer look at displacement,

land rights and the years of living marginally.

We had

no worries about land before," says the old man. "We

believe God possesses it all. He gave us plenty to share and

we just took the amount we needed to survive. After all these

years, we regret why we never cared for ownership of land,

now that we have nothing." These are the words of 95-year-old

Jonik Nokrek from Chunia, of Pirgachsa, Madhupur. While almost

the entire community including his children converted to Christianity,

this old man still has faith in his traditional religion --

Shangsharek. Jonik Marak Nokrek is the oldest man alive with

Shangsharek faith in the Mandi community of Bangladesh.

Nokrek

sits in front of the artefacts on display at the Shilpakala

Academy as part of the three-day Indigenous People's Cultural

Festival organised by the Society for Environment and Human

Development (SEHD). In the backdrop, a huge crowd cheers at

the indigenous girls performing traditional dances. During

the festival held 17 to 19 March, Nokrek was seen telling

stories of his past and showing artefacts to the crowd. He

seemed just happy to be there, whereas at the dialogue table,

conservation of indigenous people's culture was a well mused

over issue. Nokrek

sits in front of the artefacts on display at the Shilpakala

Academy as part of the three-day Indigenous People's Cultural

Festival organised by the Society for Environment and Human

Development (SEHD). In the backdrop, a huge crowd cheers at

the indigenous girls performing traditional dances. During

the festival held 17 to 19 March, Nokrek was seen telling

stories of his past and showing artefacts to the crowd. He

seemed just happy to be there, whereas at the dialogue table,

conservation of indigenous people's culture was a well mused

over issue.

The slogan

for this year's festival is "Cultural diversity is our

pride". Within a few years, much has been said about

protecting this sense of pride. Thus, every year indigenous

women belonging to different ethnic groups perform songs and

dances, amid the thunderous applause that they receive the

demand for the protection of cultural diversity gets postponed

until the next year's Adivasi festival.

The Adivasis

of the country demonstrate unique cultures, traditions and

knowledge. There is always debate about the number of indigenous

ethnic groups living in Bangladesh. According to the last

census held in the year 1991, around 1,205, 978 indigenous

people live in Bangladesh and the total number of indigenous

ethnic groups is 27, according to the government estimate.

There are non-government bodies that put the number in between

40 to 50. Even Santu Larma, the Chakma leader, recently claimed

that there are 40 different groups of Adivasis in Bangladesh.

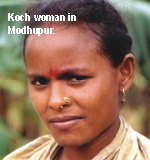

Among them the Chakma, Tanchangya, Tripura, Mro, Murong, Marma,

Bawm, Pankhua, Khayang, Chak and the Lushai live in the Southeast

(Chittagong Hill Tracts) region. The Santal (Saotal), Oraon,

Munda, Malo, Mahato, Koch, Rajbangshi in the north, the Mandi

(Garo) and Hajongs in the north-central plains, Monipuri,

Khasi, Patra and tea garden communities live in the north-east

and the Rakhains in the coastal belt. All of these communities

with their diverse culture, language and tradition contribute

to making Bangladesh a culturally rich country.

But, the

boundary of cultural life goes far beyond the occasional stage

performance of dances, songs and drama. Language, knowledge,

thought, belief, tradition, technology, behaviour, rights

and festival-- all these are part of the cultural life of

a community.

Drifted

away from home Drifted

away from home

The boundary stretches as far as land rights. "If a community's

right to land -- their main source of livelihood -- and its

resources are not secured, efforts for protection of culture

become meaningless," says Philip Gain, General Secretary

of SEHD, at the seminar on Adivasi Life, Language and Culture

held on the second day of the festival. Discussants recognised

land rights issues to be the main source of crisis for the

indigenous people. For the Adivasi people both in plains and

in the hills, management of land and ownership has an altogether

different meaning. Community sharing of every piece of land

is still a common practice. Ownership of the land was never

a concern for them.

Although

settlement started during the 1960s, the huge Bangali settlement

in the hill during the 1980s and the government allocation

of land to them have kick started a major crisis for the Adivasi

people. Land ownership was an unusual concept to them. When

these communities began to apprehend this new idea they have

already been displaced from their land.

In the

plains, Adivasi people like Oraon, Santal or Mandis have never

had any sense of ownership. They simply lost their land to

Bangalis. Bangali and indigenous communities lived alongside

in the plains but always with a feeling of incognisance. Two

entirely different cultures failed to merge. Just like what

happened in every other place in the world, the indigenous

communities of Bangladesh lost their resources to the majority

population.

“Batidaan

used to be the determinant of ownership in our society. The

community using the land is supposed to light up a lamp there

during the night. It was that simple," says Surendranath

Sarkar of Puthia, Rajshahi.

Surendranath,

an Oraon by birth, is participating in the festival as a member

of the Puthia Upazila Adivasi Unnayon Shangstha. He was stating

how most of the Oraon people of his area are now land-less.

"The government acquired all our land and they are supposed

to distribute it to the destitute of the area. Most of the

time, people with muscle and money get the land. Our boshot

bhita is now being distributed as Khas land." Surendranath,

an Oraon by birth, is participating in the festival as a member

of the Puthia Upazila Adivasi Unnayon Shangstha. He was stating

how most of the Oraon people of his area are now land-less.

"The government acquired all our land and they are supposed

to distribute it to the destitute of the area. Most of the

time, people with muscle and money get the land. Our boshot

bhita is now being distributed as Khas land."

He also

remarks that there are no examples of any Oraon person ever

receiving land from the government. "Oraons are now among

the most destitute in the area and it would have been wise

if the government, at least, donated the piece of khas land

that used to be our homestead." As the land cannot be

retrieved, Surendranath now feels that the Oraon community

needs special attention from the government or the NGOs to

reclaim what rightfully belongs to them. What is imperative

is the support to revive their traditional living and to improve

their condition.

Various

NGOs are now working in the Adivasi area to improve their

standard of living. Their work, to some extent, introduced

better and alternative lifestyle to the Adivasi people. However,

Adivasi leaders feel that the participation of the Adivasis

is needed in the policy making of these NGOs. Sontosh Soren,

Regional Director of Karitas in the greater Rangpur region,

points out, "Most of the projects aimed for the Adivasis

do not correspond with their culture and social principles."

Being a member of the Santal community himself, Soren apprehends

the need for Adivasi participation. He says, "Adivasis

are simple folk. Their needs often do not match with the ongoing

projects." According to Soren this has led to 'unusual

problems' for the adivasis.

Soren

explains, "For instance, different NGOs are now including

the Adivasi people in their micro-credit programme. The idea

of micro-credit has no meaning for the Adivasi community.

Having no sense of loan and its down payment, most of the

times, Oraons or Santals receiving the loans fail to use it

properly." Soren

explains, "For instance, different NGOs are now including

the Adivasi people in their micro-credit programme. The idea

of micro-credit has no meaning for the Adivasi community.

Having no sense of loan and its down payment, most of the

times, Oraons or Santals receiving the loans fail to use it

properly."

"Many

Adivasis in my working area are now burdened with micro-credit

loans," he adds. Shoren feels that before including them

to any programme, "Adivasis should receive special training.

First they should get acquainted with the new idea."

The

forest dweller's cry

One of the most disturbing by-products of modernisation is

that Adivasi people's access to land resources is being gradually

curtailed. Similarly, their lives are being detached from

the forestland, another source of their livelihood, and, from

the Adivasi point of view, wisdom. Much of their knowledge,

techniques, values, dances, songs and stories are derived

from the forest. Traditionally, most of the indigenous people

of Bangladesh lived in and around forest regions. As their

lives are closely associated with it, for centuries they protected

the resources and the spirit of the forest taking only whatever

little they needed to survive.

The lion's

share of the forestland of Bangladesh is now 'reserve forests'.

These include Chittagong (CHT) region in the Southeast (322,

331 ha) and Madhupur tracts in the north-central region (17,

107 ha). The reserve forest is government property and managed

by the Forest Department. There are small areas of protected

forest, which is mainly an intermediate category awaiting

formal recognition as reserve forest. Another legally classified

category is known as 'privately owned forest'.

The conversion

of the reserve forest has serious consequences on the lives

of the Adivasis. Once a land is declared reserved forest,

the forest-dwelling people lose access. Collection of fuel

wood and other forest resources for household use only is

a traditional right of the indigenous people. Reserve forest

expansion has led to the displacement of many indigenous families

living in the forestland, as they find it difficult to cope

with the changed situation.

'Environmental

refugees' among the Adivasis are on the rise. During 1981/82,

the Forest Department introduced reserve forest plans to CHT

region. Zuam Lian Amlai, President of the Bawm Social Council,

Bangladesh, came all the way from Bandarban to join the festival.

He says, "We did not receive proper notice from the authority

about reserve forest plan. Many Bawm families in Bandarban

moved out of the area, as they failed to manage their lives

without the access to the forest." "Bawm people

reserve forestland for their own need. They used to have trees

encircling their village. The circle protected them from fire.

They collect food, firewood and medicinal plants from the

forestland. It is a part of their heritage," Amlai relates. 'Environmental

refugees' among the Adivasis are on the rise. During 1981/82,

the Forest Department introduced reserve forest plans to CHT

region. Zuam Lian Amlai, President of the Bawm Social Council,

Bangladesh, came all the way from Bandarban to join the festival.

He says, "We did not receive proper notice from the authority

about reserve forest plan. Many Bawm families in Bandarban

moved out of the area, as they failed to manage their lives

without the access to the forest." "Bawm people

reserve forestland for their own need. They used to have trees

encircling their village. The circle protected them from fire.

They collect food, firewood and medicinal plants from the

forestland. It is a part of their heritage," Amlai relates.

The reserve

forest status, however, has failed to protect the biodiversity

of the forestland. Deforestation of the CHT forest is in full

swing. "Instead of protecting the forestland, we believe

the Forest Department is destroying it. Tree felling increased

after the arrival of Forest Department in the region. Hundreds

of mature trees are auctioned off for commercial felling.

The timber smugglers have close ties with the Forest Department

authority," claims Amlai.

The Adivasis

are also threatened by the introduction of commercial or industrial

plantation such as rubber and pulpwood. Huge areas of natural

forestland are usually cleared for plantation, land that used

to be the livelihood source of many indigenous people. While

rubber plantation is considered a major failure in the region,

pulpwood plantation provides raw material, largely for the

Karnaphuli Paper Mill. This commercial plantation has been

blamed for major deforestation in the area, as most of the

trees are felled when they are mature. Hills shaved of their

greenery are a common sight in the region, a devastating blow

for the indigenous people.

As the forest areas are diminishing for the Adivasi people,

their livelihood is gradually changing. The plantation by

Forest Department is hardly recognised as forestland by the

Adivasis. "They have created a garden not forest,"

says Zuam Lian Amlai. "They cleared natural vegetation

and planted alien species like acacia or eucalyptus and also

some segun and gamar. These planted trees

are of no use for the Adivasis and failed to create a forestland

as they are felled when they are mature." However, Amlai

does not want to blame only the Forest Department for forest

destruction. "Large-scale timber smuggling is closely

associated with the poor economic condition of the area,"

he adds.

Amlai

also points out that, "Land for jhum cultivation

is decreasing, as huge area of jhum land has now

become reserve forest." As the amount of land has decreased,

the contest for every piece of cultivable land intensified

among the ethnic groups in the hills. Bangali settlement also

created pressure on the jhum land. Every jhum

land requires a long period of interval before another crop

can be cultivated. This interval helps the land to retrieve

all the nutrients and keeps it fertile. But gradually the

rotation period is shrinking. Amlai

also points out that, "Land for jhum cultivation

is decreasing, as huge area of jhum land has now

become reserve forest." As the amount of land has decreased,

the contest for every piece of cultivable land intensified

among the ethnic groups in the hills. Bangali settlement also

created pressure on the jhum land. Every jhum

land requires a long period of interval before another crop

can be cultivated. This interval helps the land to retrieve

all the nutrients and keeps it fertile. But gradually the

rotation period is shrinking.

Another

major cause of displacement of thousands of Adivasis has been

the Kaptai Hydro Electric Dam. Completed in 1963, the dam

created a huge reservoir of water, which submerged 250 square

miles of prime agricultural land and forestland.

Most of

the plain land forest in Madhupur is also out of reach for

the adivasi people living there. A similar scenario prevails

in the area. Madhupur was announced a Government Forestland

in the year 1984. The tenants of the forestland, mostly Mandis,

were largely displaced. Very few still living in the area

have access to its resources. Recently, the Forest Department

started building a wall around the Madhupur forest in order

to create a so-called 'eco-park'. To build the 3,000-acre

wall they have cleared a large area of the forest instead

of protecting the sal trees. This wall is considered a major

threat to the culture and livelihood of the Mandi people.

A proper

safety net is needed. There is no safety net to protect the

rights of these people. The constitution of Bangladesh in

article 15 of Fundamental Principles of State Policy section

says, "It shall be a fundamental responsibility of the

State to attain, through planned economic growth, a constant

increase of the productive forces and steady improvement in

the material and cultural standard of living of the people."

But Adivasi people hardly see any justice being done to their

problem. There is a SAARC Social Charter on Adivasi people

but the Adivasis feel that it has become a "useless piece

of document".

Article

27 of the constitution also says, "All citizens are equal

before law and are entitled to equal protection of law".

Zuam Lian Amlai reveals that most of the times it is not the

case for Adivasi people. "Crime against Adivasis often

go unpunished," he says. Access to legal aid is very

limited for Adivasi people.

Another

important aspect regarding legal aid is that there is no Judge

Court in the three hill districts. There are Magistrate Courts,

however, they cannot settle land-related disputes or severe

crimes like rape and murder. To resolve these matters there

is one Additional Divisional Commissioner appoin-ted but the

office of the commissioner is situated in Chittagong. For

Adivasi communities, or Bangalis living there, it is not convenient

to go all the way there with legal complaints. Adivasi communities

have their own social regulations. They try to solve any problem

through dialogue in the beginning. Another

important aspect regarding legal aid is that there is no Judge

Court in the three hill districts. There are Magistrate Courts,

however, they cannot settle land-related disputes or severe

crimes like rape and murder. To resolve these matters there

is one Additional Divisional Commissioner appoin-ted but the

office of the commissioner is situated in Chittagong. For

Adivasi communities, or Bangalis living there, it is not convenient

to go all the way there with legal complaints. Adivasi communities

have their own social regulations. They try to solve any problem

through dialogue in the beginning.

But there

are incidents that require going to the police station. "When

we go to the police station seeking legal assistance for murder

or rape, most of the times law enforcers do not respond properly

to our complaints". Article 28(1) of the constitution

says, "The State shall not discriminate against any citizen

on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or place of

birth". However, state agencies often do not follow the

declaration. Because of lack of cooperation from the law enforcers,

Adivasis try to avoid lawsuits.

There

is a separate ministry in the CHT, addressing the needs of

the Adivasis in the hills. However, Adivasis in the plains

have no way of having their rights protected. Completely desolated

and forgotten among them are the tea plantation workers' community.

State agencies and the general people are oblivious to their

condition.

These

tea plantation workers belong to various indigenous groups.

Their number is currently 120, 000. During colonial rule,

the British brought these people from India as cheap labour.

Since then their condition has remained virtually the same.

The laws passed in the year 1865 still exist in the estate

and are still in use. These

tea plantation workers belong to various indigenous groups.

Their number is currently 120, 000. During colonial rule,

the British brought these people from India as cheap labour.

Since then their condition has remained virtually the same.

The laws passed in the year 1865 still exist in the estate

and are still in use.

"This

law is a complete violation of the ILO convention," informs

Philip Gain who is currently working on the issue. Daily wage

of a tea plantation worker is Tk 28, whereas according to

the ILO convention the minimum wage of a labourer has to be

Tk 48. "Tea plantation workers are bonded labourers.

Tea plantation workers' offspring become tea plantation workers.

It is like an unbreakable rule," adds Gain.

Even minors

are forced to work on the tea estates. There is no such thing

as maternity leave, which is why mothers are forced to work

right after delivery with the new-born hanging on their backs.

Health and educational facilities are very poor. "These

people toil hard to earn valuable foreign currency for Bangladesh,"

says Gain.

To give

what is just to the Adivasi people, Raja Devasish Roy, chief

of the Chakma circle, stresses, "The Constitutional recognition

to Adivasi rights is very important." This was a popular

demand during the festival.

The

Adivasi festival ended with observation that indigenous communities

living in all corners of Bangladesh are marginalised and disadvantaged.

Exulted audiences at the Shilpokola Academy admired their

presence on stage, romanticised about their vibrant traditions.

This romanticised package of songs and dances and colourful

dresses are mere aesthetically pleasing exhibits during the

festival. It is tantamount to turning a spectrum of people

and their cultural heritage into museum showpieces; like some

added exotic elements to spice up the lives of the majority

Bangalis as well as foreign tourists, while the oldest Shangsharek

man living at Chunia conveys that he does not have enough

money to buy even a pair of glasses. The

Adivasi festival ended with observation that indigenous communities

living in all corners of Bangladesh are marginalised and disadvantaged.

Exulted audiences at the Shilpokola Academy admired their

presence on stage, romanticised about their vibrant traditions.

This romanticised package of songs and dances and colourful

dresses are mere aesthetically pleasing exhibits during the

festival. It is tantamount to turning a spectrum of people

and their cultural heritage into museum showpieces; like some

added exotic elements to spice up the lives of the majority

Bangalis as well as foreign tourists, while the oldest Shangsharek

man living at Chunia conveys that he does not have enough

money to buy even a pair of glasses.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|