|

Special Feature

Sweatshop Tales

Modern Kuwait represents all the glamour and opulence of an oil-rich country. Behind the glamour is the toil of the hundreds and thousands of migrant workers. Among them are 240,000 Bangladeshi workers many of whom are underpaid, work 7 days a week and live in appalling conditions defying all international labour laws. Too scared to complain to the authorities because their passports are held hostage by their employers, placed into shady work situations by a Bangladeshi manpower industry that is wildly unregulated and endemically corrupt, on July 28 the Pandora's Box finally exploded. Hana Shams Ahmed

Twenty-seven-year-old Mohammad Shahjalal Saiful used to work as a manager in a local grocery store in Noakhali. Every month he used to make Tk 3500 at the store. When a friend approached him saying that he had the potential to make more than Tk 12,000 a month working less hours he was overjoyed. He got in touch with a travel agency named Friends Travels in Fakirapul, which provided him with a visa to Kuwait and a contract with a cleaning company that promised to pay Kuwaiti Dinar 50 (Tk 12,832) per month. Saiful had to pay Tk 2 lakh to purchase the whole package though. He had little money of his own so he ended up borrowing from his friends and relatives. He thought it was money well spent though. He would be able to start repaying very soon.

On June 12, 2005 Saiful arrived in Kuwait. It was a different story here though from the one the travel agency had told him. There was no job waiting for him and for three months he remained unemployed. He finally got a job at a cleaning company called Al Abras for Dinar 20 (Tk 5,132) a month. His passport was taken away from him by the employer of the company and one month's salary was withheld. He used to work 8 hours a day, 5 days a week.

From the beginning of this year prices of essential items started to skyrocket in the market. According to Saiful, rice that used to cost Dinar 4.5 a sack went up to as high as Dinar 10 a sack. According to The National Labour Committee a Kuwaiti public sector employee who was earning USD 45,000 a year or less, received a USD 188 a month wage increase to compensate for the price hike. However, the wages of the migrant workers remained the same. Saiful and many others like him now found it almost impossible to live on their meagre wages.

On July 21, Saiful, along with 80,000 other Bangladeshi (some Sudanese, Indian and Egyptian) workers under 23 companies, went on strike. According to the Arab Times, about 2,000 Bangladeshi workers, employed by Al-Jawhara Company for Stevedoring and Cleaning in Hassawi in Kuwait, destroyed six vehicles and injured five camp officials. Kuwaiti police beat up and arrested about 1,000 workers for staging demonstrations. They were all protesting against exploitation by their employers. Most of them were in much worse conditions than Saiful. Many of the workers alleged that they had to work 7 days a week and had not been able to take leave over the last 8 to 10 years. Even if a worker was granted leave for returning home, the company charged them Dinar 30 as security money and the employers never gave their money back. Some of them were forced to work 16 hours a day without any payment for overtime work and many of the employers beat up the workers. All of them were getting Dinar 20 or less although they were promised Dinar 50 in their original contract.

Although most of the progressive media in Kuwait spoke against the violation of the rights of the workers they also pointed out to the general sense of xenophobia amongst the Kuwaiti public. In an article titled 'Stop disgracing Kuwait's name!' that appeared in the Kuwait Times, journalist Badrya Darwish wrote, “Put yourself in their shoes just for a moment. You are thrown in a place with 20 people in a room and maybe 100 using a single toilet. Where you cannot get a shower for over a month...no proper food...working from 5 in the morning till 5 in the evening. And on top of that, no salary. What will you do? Won't you opt to stealing or scavenging in dustbins to find food and recyclables like cats and rats? And then we dare open our big mouths sitting in our air-conditioned lounges and give statements like 'Oof, these Bangladeshis are so dirty... they are so smelly... they are thieves... they dig in bins... deport them... Kuwait doesn't need them, etc.”

More than a thousand workers from Kuwait were sent back without their payment arrears. The sights that greeted Bangladeshis in the country was quite the contrast from what is normally seen at the airport. Instead of the smiling, identically uniformed queue of young men there was in place men limping out of ZIA without their shoes, some wearing lungis, some without any luggage, injured and crying.

A Kuwaiti blogger posted a photo taken with his cell phone of the workers standing in a queue at the Kuwaiti airport with this caption, "Here is a picture of some of the Bangladeshi trouble makers leaving Kuwait last Wednesday."

One blogger commented "good riddance, even though it was shameful from our part.....!"

Yet another commented, "Not paying them their obscenely low salary of 20 KD for MONTHS... if I were them I would have done a lot more damage!"

At the same time that Kuwait was deporting workers many workers were sent back from Saudi Arabia. A Saudi news website, Elaph, lashed out at Bangladeshi workers, no holds barred on racism talking about Bangladeshi "criminal nature" and said that "the French were most right in describing them as while ants who eat all what they see without discrimination."

More than a thousand workers from Kuwait were sent back without

their payment arrears.

This is of course not the first incident where cheated and abused Bangladeshi workers have been blacklisted for asking for their rights. In April 2005 more than 700 Bangladeshi workers stormed the Bangladesh embassy in Kuwait causing damage inside the premises. The protesters complained that they had not been paid for five months and demanded embassy officials take action. The Kuwaiti government instead of taking action against the corrupt employers decided to stop hiring workers in late 2006. The nation now hires workers only for selective companies. This time Kuwait has decided not to renew residency visas of Bangladeshis doing menial jobs, saying that these workers "are a threat to state security and bring unnecessary international focus on the country". 80 percent of the Bangladeshi workers make the lowest wages in the country. Bahrain stopped issuing work permits to Bangladeshis, excepting the professionals, after a Bangladeshi mechanic killed a Bahraini man after an argument over pay. Bangladesh's largest labour market Saudi Arabia, home to around 15 lakh Bangladeshis, imposed a ban on recruitment of Bangladeshis in households and the agriculture sector. Thousands left the country because it unofficially stopped renewing residential permits to Bangladeshis, who want to get new jobs when their job contracts expired.

In June, a US State Department report on forced labour and sex trade, placed Kuwait in the 'worst offender' category alongside fellow Gulf states Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman. The intensity and size of the protests this time must have worked like a wake-up call for the Kuwaiti authorities. The government blacklisted more than five companies of that country for violating labour laws and said that the licenses of these companies could be cancelled and their owners could receive up to three years of imprisonment. Kuwait's Justice Minister Hussein Al-Huraiti said illegal practices by the country's firms and shortcomings in law enforcement by authorities concerned have led to grave violation of workers' rights. The government also announced a monthly minimum wage for foreign workers -- Dinar 40 (Tk 10,306) for unskilled workers and Dinar 70 (Tk 18,035) for security guards.

Nazrul Islam Khan, a former ambassador to Kuwait (June 2004 to August 2006) and the secretary general of Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies (BILS) says that the government of Bangladesh needs to equip the embassies better if they are expected to look out for our workers' welfare. "The workers have many expectations from the embassy," says Khan, "unfortunately more than 40,000 workers go to the country with no official documents and no knowledge of the embassy. The embassies only get to know of their existence when there is trouble."

The labour department of the Bangladesh embassy in Kuwait has one labour attaché, two local representatives, one clerk and one accountant to deal with the problems of 240,000 migrant workers. This is the importance that the Bangladesh government gives to the workers who bring in millions of dollars worth of foreign remittance. "The labour wing of the embassy should have offices in places where there is a concentration of workers," says Khan, "not providing the budget to have such offices is a failure of the government."

He also said that it's very important for the representatives sent to Arab countries to know the local language. "Kuwait is the fourth highest remittance sending country to Bangladesh," says Khan, "the government needs to raise the budget for the labour wing of the embassies."

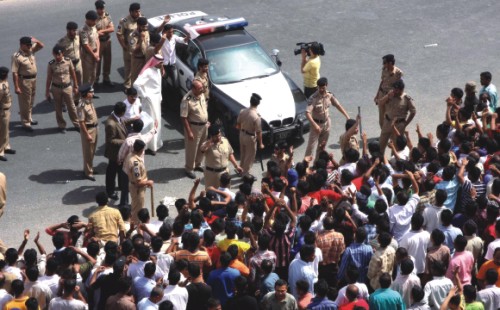

Kuwaiti police arrested thousands of Bangladeshi workers who were protesting in human work conditions and their non payment of salaries for months

Kuwait is the world's seventh largest oil exporter. According to the National Labour Committee, Kuwait's GDP is expected to grow 6.8 percent this year to USD 172.4 billion. Kuwait's trade surplus is running at USD 84 billion this year. Government revenues for the current fiscal year (April 1, 2008 through March 31, 2009) are also projected to grow by 40 percent, to reach approximately USD 129 billion. Even after all conceivable expenses, the Kuwait government should end the year with a fiscal surplus of USD 66.21 billion.

Ninety percent of Kuwait's private sector workers are non-Kuwaiti. Sixty-three percent -- or 2.3 million people out of a total population of 3.4 million -- are expatriates. A typical migrant worker in Kuwait earns just USD 75.23 a month, this means that after deducting the average USD 39.50 the workers spend in food, they are left with just USD 35.86 a month to meet all other expenses and pay off their debts. This is what ignited the strike. For years the government of Kuwait did not lift a finger to enforce its own labour laws or take a single step to end the rampant abuse and exploitation of the hundreds of thousands of workers trafficked to Kuwait.

The demands of the protesting workers from Bangladesh are fair and should have been ensured within the four walls of their workplaces, not taken to the streets -- payment of what had been promised in the contracts, free health insurance promised according to their contracts, one day off per week, improved dorm conditions (translated, not living like caged animals), no abuse at work, payment for work permits, earned vacation leave after two years of work, guarantee that all back wages owed to the deported workers are paid and compensation for deported workers.

Governments that employ foreign workers seem to always work on a certain level of xenophobia that is reflected in the attitude towards the workers by the general public. These workers are hired because no one in these oil-rich, capitalist countries will do such dirty and dangerous jobs at such paltry pay with no health insurance. The employers of these countries know that these uneducated and desperate men will not complain and will endure inhuman work pressure to pay off their debts especially if their passports are taken and the fear of the stick is put into them. It only needs another paltry bribe to feed into the greed of the recruitment agencies in the source countries to ensure a good supply of workers using an obscurantist approach. The government of Bangladesh is too busy counting its remittance dollars; officials patting each other's backs as the remittance graph makes an upward climb. International organisations get together labour 'experts' from different countries in 5-star hotels for daylong seminars discussing the 'welfare' of 'those brave migrant workers'. But men like Saiful still come back to Dhaka empty handed, having made his contribution to the country's economy, but none to himself or his family. And the cycle of deception, exploitation and abuse continues.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |