|

<%-- Page Title--%> Book Review <%-- End Page Title--%> |

||||||

|

<%-- Volume Number --%>

Vol 1 Num 146

<%-- End Volume Number --%>

|

|

March 19, 2004 |

|||||

|

<%-- Navigation Bar--%>

|

WILLIAM

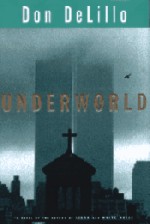

BOYD reviews Underworld by Don DeLillo ‘It was a memory that clarified the connections,' muses Nick Shay at one point in this novel -- Nick Shay being the central figure and occasional narrator of this extraordinary book. Indeed, if such a massive work can be rendered down to a one-sentence pitch it would be fair to say that the book is about memory --the memory of the second half of this fraught, embattled century and about the business of clarifying connections. We are talking about connections that underpin the individual life: connections between people, between private moments, public events, feelings, encounters and objects. DeLillo's grand schema is to chart these undercurrents, this hidden matrix, the invisible warp and weft that knit together our human existence. We all attempt this, of course, from time to time, try to plot and analyse, tabulate and detail the route we have taken. Hindsight is a great retrospective tidier and organiser of the forking paths we have chosen. But what of the connections we don't see? What of the links we haven't spotted? If only we knew what the underworld of our hidden lives revealed, what tangential touchings there were, all the secret causal chains. If we could expose the concealed plumbing and wiring of our brief moment in time our life would, in a way, truly be complete, be fully understood and fixed in history. But how could we possibly achieve this? We can sense them there, instinctively, these secret connections, but we can never trace them through all the buried circuitry. Only the all-seeing God, some might say, could highlight the sidetracks and U-turns, the back-doubles and sudden veerings-off. Only a god or a novelist. The novel's central narrative is Nick Shay's, but other narratives spin off from it, belonging to those he knows and his loves and hates - family and friends, colleagues and casual acquaintances. Nick, born in 1935 or '36 (the same age as DeLillo, incidentally), grows up in the Bronx, in some poverty and deprivation, a wild unruly kid, probably heading for trouble. He thinks his missing father, a small-time bookie, who walked out one night to buy some cigarettes and never returned, has been 'whacked' by the Mob, and his adolescence is violent and darkly troubled. He has an affair with a married woman and then comes the defining twist. Aged 17, in a meaningless accident, he shoots and kills a friend. He is sentenced for negligent homicide to three years in a juvenile correctional facility and, grimly happy to do his time, he sets about acquiring an education. The novel is full of such subtle and nuanced revelations. As we read we become privy to them because of the book's elaborate construction. We know all about Long Tall Sally's fate as a monument to conceptual art long before we see her at deadly work over Vietnam. When we meet Chuckie we realise we have already spent a day with his father in his Madison Avenue office, the day he decides to give his son the famous baseball. The book starts in 1951 and moves forward immediately to 1992. We cut back and chop about through the decades without regard to chronology. We learn about Nick's wife's affair long before we find out he's a convicted teenage murderer. The link between the hydrogen bomb and human garbage (what we excrete comes back to consume us this century producing the most deadly waste ever created) is established early and its totemic and cataclysmic significance slowly expands as the novel progresses. It is a bold, demanding and almost daunting structure to impose (and done with consummate artistry) but absolutely essential for the novel's overriding metaphor of hidden connection, of buried meaning to function as required. The novel, as Henry James sagely observed, is a loose baggy monster. This great asset means that the form is unbelievably generous and can withstand stresses and strains that would make other narrative mediums collapse and implode. Underworld is a rousingly impressive achievement in almost every novelistic department - dialogue, structure, timing, precise description, heartfelt veracity and the rest. Of course in a book of this size there are inevitably longueurs. My own feeling is that, conceivably, one would be even more admiring of it had it been 500 pages long instead of 800. Also the character of Klara Sax, a major counterbalance to Nick, never fully engages, in my opinion, and the New York art scene episodes of the Sixties and Seventies read a little thin. But these cavils are luxuries.

|

||||||