| |

Still, Reel and Reality Bites

The Photographic Odyssey of Anwar

Hossain

Mustafa

Zaman

European

Rhapsody European

Rhapsody

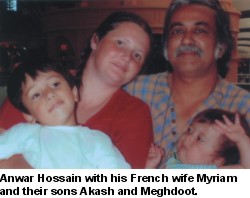

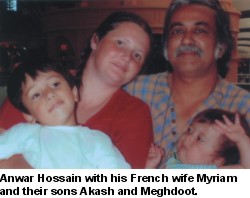

"The mental success and the earthly failure,"

is Anwar Hossain's phraseology that sums up his life

in retrospect. It also reveals an attitude and an outlook

that hinges on the pursuit of life rather than material

success. A man in "self-exile" since 1993,

Anwar is frank about his dilemma in living in France

where he finds a populace intoxicated with the energy

of life as well as art yet trapped in a social infrastructure

that tends to commodify art and every adventure that

life has to offer. He testifies, "When some people

started to see me as a member of Magnum or Gama, I was

told by them... these extremely important people...

which I would like to quote verbatim 'Its a pity Anwar

that you have spoiled thirty years of your life photographing

an insignificant country like Bangladesh'". His

reply to this always used to be the same. He answered

back as a rule that most of the world is third world

and "My whole oeuvre is the ultimate essay or the

Iliad of the third world people and their condition."

"Third world means humanity, it could be representative

of that...," says Anwar. He has all the doubts

stored in one nook of his discursive mind for people

who are churning out works that fit the definition of

the third world set by the first world.

"There

is too much dignity in your work... " was the accusation

that Anwar had to stumble upon in his first few encounters

with the first world dignitaries. In lieu of the plethora

of images that cross the subcontinent volleyed towards

the west, Anwar's humans, however destitute or encumbered

they are with material concerns, seem to want to speak

of life in all its primal glory.

Home-bound Home-bound

Work brings this master photographer back home. He is

here every once in a while. Though many may not have

any inkling of how out of 20 best Bangla movies produced

in this land, Anwar's photographic signature has made

a difference in 15 of them all. Constant homebound trips

made it happen. Yet, this is a rough figure. The most

important bit lies in the exquisitely done cinematography

of Emiler Goenda Bahini, Puroshkar, Dohon, Hulia,

Chitra Nadir Parey, Nadir Nam Modhumoti, Lalshalu,---

movies that have earned considerable critical acclaim.

Their are soon to be released works like Lalon that

will again reveal his acumen as a cinematographer.

Looking

Back: The First Scene Looking

Back: The First Scene

"Working in the movies opened up a 'Pandora's box'

for me, not in the negative sense of course..."

says Anwar. The movie Shurjo Dighol Bari revived his

passion and set him on a course through memory lane.

"Everything came together in the movie; my childhood,

the paintings I used to admire, the life I led, my education

in Pune and all the photographic experiences, everything

came together for an explosion that created Shurjo Dighol

Bari," recalls Anwar.

This

was his first venture. It also became one of the milestones

in the history of Bangla movie.

At

a village in Manikganj, back in 1980 the longhaired

and big-moustachioed Anwar Hossain with his recently

acquired degree from Pune, India was filming his first

scene decked in a lungi. He was directing his camera

assistants and crew to ready the scene for the first

shoot. About the contingent that was there with him

he now reflects, "We were all equipped and with

people who despite their very, primitive idea about

movies had a kind of enlightenment in their soul to

do something extraordinary. It certainly catalysed my

vision."

The

crew that he worked with was not at all well versed

in movie making. "The problem that started from

the very first scene of Shurjo Dighol Bari lied in the

fact that my crew had exactly the opposite ideas and

practice of film making compared to what I had achieved,"

says Anwar.

The

scene had Joygun (Dolly Anwar) and Mymoon (Elora Gaohor),

her daughter, doing some chores in floodwater next to

the house. "The water was quickly receding and

we panicked," remembers Anwar. He was shooting

from the boat that was stabilised with four banana trees

propped up in the water. Anwar remembers his handsome

assistant cameraman in John Travolta-style garb and

hair in meticulous detail. "He had this very high

heeled black shoes on, Travolta type of course, and

he was a sight of incredible contrast. I was wondering

about how this person would be assisting me..."

says Anwar. The

scene had Joygun (Dolly Anwar) and Mymoon (Elora Gaohor),

her daughter, doing some chores in floodwater next to

the house. "The water was quickly receding and

we panicked," remembers Anwar. He was shooting

from the boat that was stabilised with four banana trees

propped up in the water. Anwar remembers his handsome

assistant cameraman in John Travolta-style garb and

hair in meticulous detail. "He had this very high

heeled black shoes on, Travolta type of course, and

he was a sight of incredible contrast. I was wondering

about how this person would be assisting me..."

says Anwar.

From

the very beginning, everything went wrong. There were

six reflectors all together and Anwar wanted only one

for the two actresses, two for the ducks, one for the

mango tree and another for the sloppy riverside and

the last one was set to give the house and its bamboo

trees salience. His crew was shocked. "Everyone

was objecting to the fact that the actors had only one

reflector, never in their life did they see such a technique.

With few working in the field of cinema for the last

seven or ten years, and the assistant cameramen with

experience of ten or so prior projects, they were saying

that they never had this bitter experience of having

reflectors allocated for the surrounding objects,"

recalls Anwar. From

the very beginning, everything went wrong. There were

six reflectors all together and Anwar wanted only one

for the two actresses, two for the ducks, one for the

mango tree and another for the sloppy riverside and

the last one was set to give the house and its bamboo

trees salience. His crew was shocked. "Everyone

was objecting to the fact that the actors had only one

reflector, never in their life did they see such a technique.

With few working in the field of cinema for the last

seven or ten years, and the assistant cameramen with

experience of ten or so prior projects, they were saying

that they never had this bitter experience of having

reflectors allocated for the surrounding objects,"

recalls Anwar.

Context

for Anwar has always been important. In fact in his

stills as well as in his cinematography, contextual

representation is what he so daringly achieves. In the

first shoot Anwar depended on the reflection of the

water too. Life in its truthfulness and natural phenomenon

are the two elements that always drove him. In the shooting

of the first scene of the historically important movie

that Shurjo Dighol Bari later became, the man behind

the camera took charge and transformed a bleak scenario

into an insightful observation of reality. Sheikh Niyamat

Ali, the director of the film, gave his cameraman full

support. Whatever Anwar proposed, he gave the green

light to it and it is this freedom with which Anwar

applied to his art. One must recall that the same man

who was so particular about using reflectors for the

whole scene, discarded their use while shooting the

scenes in the city in the same movie. "I wanted

to create a harshness that would be representative of

city life," said Anwar back in 2000 in an interview

with the Star Weekend Magazine. Context

for Anwar has always been important. In fact in his

stills as well as in his cinematography, contextual

representation is what he so daringly achieves. In the

first shoot Anwar depended on the reflection of the

water too. Life in its truthfulness and natural phenomenon

are the two elements that always drove him. In the shooting

of the first scene of the historically important movie

that Shurjo Dighol Bari later became, the man behind

the camera took charge and transformed a bleak scenario

into an insightful observation of reality. Sheikh Niyamat

Ali, the director of the film, gave his cameraman full

support. Whatever Anwar proposed, he gave the green

light to it and it is this freedom with which Anwar

applied to his art. One must recall that the same man

who was so particular about using reflectors for the

whole scene, discarded their use while shooting the

scenes in the city in the same movie. "I wanted

to create a harshness that would be representative of

city life," said Anwar back in 2000 in an interview

with the Star Weekend Magazine.

The

history of photography and cinematography in Bangladesh

did not remain the same since Anwar burst into the scene

in the sixties and masterfully turned the course of

cinematography in the 80s. Though Anwar regretfully

says, "It still remains the same," while referring

to the state of cinematography and the technical supports

involved in cinema in Bangladesh. As for still photography,

he is in great opposition to working project by project

with only mercenary motive in sight. "If you are

a creator you cannot create without falling in love.

Otherwise you should call yourself a businessman, not

a photographer or a cinematographer but a photo-businessman,"

stresses Anwar. Empathy with the subject and the medium,

for him, is the only assurance of artistic excellence. The

history of photography and cinematography in Bangladesh

did not remain the same since Anwar burst into the scene

in the sixties and masterfully turned the course of

cinematography in the 80s. Though Anwar regretfully

says, "It still remains the same," while referring

to the state of cinematography and the technical supports

involved in cinema in Bangladesh. As for still photography,

he is in great opposition to working project by project

with only mercenary motive in sight. "If you are

a creator you cannot create without falling in love.

Otherwise you should call yourself a businessman, not

a photographer or a cinematographer but a photo-businessman,"

stresses Anwar. Empathy with the subject and the medium,

for him, is the only assurance of artistic excellence.

Down

Memory Lane Down

Memory Lane

How did a man who was born in a slum of Aganwab Deury

in Old Dhaka in 1948 become what he is today? The cue

to the answer lies in the fact that Anwar never regretted

his reality. The reality he was born in was his first

springboard. Being the oldest in a family of twelve,

he had to scavenge with other kids in the area to help

out whichever way a child could. "It was from the

Haat (Bazaar) of Gani Mian that we used to collect saw-dust

to sell a sack full for 8 ana (half of one taka),"

recalls Anwar who would wake up very early to finish

his home work for school and then go scavenging in the

morning. After the scavenging stint he would then go

to the bazaar and then straight to school.

Anwar

remembers how his name was often dropped from the list

of the registers though he was the first boy of his

class at the Armanitola Govt. High School. "Very

often the fees remained unpaid and though I used to

get scholarship for my position in class my name was

never mentioned during roll calling," reflects

Anwar. Anwar

remembers how his name was often dropped from the list

of the registers though he was the first boy of his

class at the Armanitola Govt. High School. "Very

often the fees remained unpaid and though I used to

get scholarship for my position in class my name was

never mentioned during roll calling," reflects

Anwar.

But,

every predicament had its other side. Struggling for

survival at such an early age, studying in the light

of one hariken (kerosene lamp) at night out in the open

porch, the aspiration to live a better life, and most

of all the joy of living, only served to widen his perspective

and bring in an intensity to his photography. Anwar

harks back to his early days to throw light, "I

wrote about the way we used to sit down in a circle

like a 'well', I delineated the surrounding--- the split

sky above, the pomegranate tree at one corner, and the

dreamy reflection on life of a child. This was hugely

appreciated by my teacher at school."

His

creative flair was aflame from the very beginning. He

kept on writing poetry. But as he grew up Anwar developed

a kinship for paint and brush. He used to get his paint,

brush and paper free of cost from the Shishu Kala Bhaban

at Art College (presently the Institute of Fine Arts).

"I wanted to become a painter," recalls Anwar.

"We had no TV or even radio for that matter, we

could not afford them back in the early sixties. So,

I resorted to expressing myself, my child-feelings,

in paper. I remember becoming some thing of an artist

in my class," adds Anwar. In 1963, when he was

in class eight, Debdas Chakrabarti, the eminent artist,

was the art teacher of his school. Anwar too, back then,

seemed all set to become an artist.

His

father, who was working as a manger at a local movie

studio, stood in his way. "It so happened that

despite the difficulties in life, and an enigmatic childhood

revolving around poverty and family obligations I stood

fifth in the SSC exam," Anwar recalls. In his family,

he was the first person to have completed the entrance

exam, which is equivalent to SSC. So the road to paint

and brush came to a close. His

father, who was working as a manger at a local movie

studio, stood in his way. "It so happened that

despite the difficulties in life, and an enigmatic childhood

revolving around poverty and family obligations I stood

fifth in the SSC exam," Anwar recalls. In his family,

he was the first person to have completed the entrance

exam, which is equivalent to SSC. So the road to paint

and brush came to a close.

The

memories of Shishu Kala Bhaban, where Anwar used to

paint in his childhood, however, haunted him even after

he took admission in Notre Damme College. "I used

to paint strange pictures. As my father used to arrange

for me to enter the theatres without tickets to see

English movies like Spiderman, Tarzan and other action

flicks to improve my English, I became so obsessed with

them that in the pictures that I painted the movie characters

prominently figured," recalls Anwar. The painter

had to give up painting to study architecture, a subject

that he never took to his heart. He saw it as "a

compromise solution."

On

the Image Maker's Trail On

the Image Maker's Trail

To be a painter was not an 'honourable' profession,

nor was photography taken as seriously as it is now

in our culture. So, what set this aspirant painter on

the course of a sinuous photographic journey? The man

whose love affair with his camera has only bloomed over

time reveals, "One of my friends at college approached

me and said he wanted to sell his camera for 30 Taka

as he was giving up photography." Anwar bought

the camera on an instalment basis.

The

eighth exposure of the first film that Anwar filled

in his newly bought camera was spent on a scene taken

from opposite Kamrangir Char. Anwar remembers how he

got down into knee-deep water to take the scene of dhopas

of Dhaka city. "This was the last exposure of that

eight exposure film, and this picture got me an award

in Bangladesh," Anwar goes back to his early start.

Golam Kashem Daddy used to run the Camera Recreation'?

Club, it was at the exhibition of the Club that he got

the award. The

eighth exposure of the first film that Anwar filled

in his newly bought camera was spent on a scene taken

from opposite Kamrangir Char. Anwar remembers how he

got down into knee-deep water to take the scene of dhopas

of Dhaka city. "This was the last exposure of that

eight exposure film, and this picture got me an award

in Bangladesh," Anwar goes back to his early start.

Golam Kashem Daddy used to run the Camera Recreation'?

Club, it was at the exhibition of the Club that he got

the award.

This

is the club where Anwar met legendary figures of photography

like M.A. Beg, Golam Mostafa, and Bijon Sarkar, who

inspired him. "I did not have money to buy films,

my scholarship money was often spent to support the

family. So, it was Shadhan Da, the great, great cinematographer,

who used to provide me with cut pieces of films that

was put into cassettes to be used in still cameras,"

remembers Anwar.

"Ultimately

I ended up buying a better camera shared by four people,

buying an enlarger shared by four people, and buying

my first colour film at 36 Taka shared by four people,"

It was around the end of the sixties that Anwar got

his hands on his first colour film which they sent to

Germany to develop. "It was very exciting to get

my own first colour film from a photographer for the

army whom I used to call Alok Da, and to see the roll

when it came back from Germany," recalls the maestro.

"Till today colour slide development is not done

properly in Bangladesh, and this was in 1969,"

adds Anwar. "Ultimately

I ended up buying a better camera shared by four people,

buying an enlarger shared by four people, and buying

my first colour film at 36 Taka shared by four people,"

It was around the end of the sixties that Anwar got

his hands on his first colour film which they sent to

Germany to develop. "It was very exciting to get

my own first colour film from a photographer for the

army whom I used to call Alok Da, and to see the roll

when it came back from Germany," recalls the maestro.

"Till today colour slide development is not done

properly in Bangladesh, and this was in 1969,"

adds Anwar.

Anwar

came a long way after that. He completed his diploma

in architecture, though never practised it in life.

He was in love with photography. "Fortunately I

did not have girl friends, and looking at girls did

not even occur to me as something interesting back then.

Therefore, I could spend my time in observing life through

the lens," Anwar says jokingly. It is the truthfulness

of photography that at last won over painting, which

is practised in isolation at one's home or studio. As

a member of a poor family who never felt poor, son of

a caring and giving mother, Anwar took life for granted.

"All the difficulties and hardship was part of

life," he feels in retrospect.

Anwar

remembers what slowly drew him to the movies. "It

was Khosru Bhai of Film Society and Badal Rahman who

pickled my young mind with ideas of exploring the reel,"

he recalls. The spectacles in movies amazed him. He

went on to study cinematography, heading for Pune in

1974 on an ICCR scholarship, causing resentment in the

family. He sat out on a journey that would later put

him in the path to greatness. Anwar

remembers what slowly drew him to the movies. "It

was Khosru Bhai of Film Society and Badal Rahman who

pickled my young mind with ideas of exploring the reel,"

he recalls. The spectacles in movies amazed him. He

went on to study cinematography, heading for Pune in

1974 on an ICCR scholarship, causing resentment in the

family. He sat out on a journey that would later put

him in the path to greatness.

"My

grandmother kept banging her head on the wall, she kept

at it and lived a longer life than my parents..."

Anwar jokingly emphasises. Braving opposition both at

home and from outside, he left behind a contingent of

teachers in BUET as well as friends who considered his

move an outright aberration. Anwar made his choice.

He now proudly proclaims, "Life changed after Pune..."

The

history of cinema in Bangladesh changed with that. Anwar

Hossain is a living legend now. The imprint of his skill

as well as his sensibility is now in demand. Though

not many films could provide him with the turf that

Shurjo Dighol Bari did. His signature is still something

that most of the new filmmakers crave to have in their

work. He often finds himself behind the camera. Though

he is not satisfied with the kind of shoddy equipment

he works with, his impression is clearly visible in

the end results. The

history of cinema in Bangladesh changed with that. Anwar

Hossain is a living legend now. The imprint of his skill

as well as his sensibility is now in demand. Though

not many films could provide him with the turf that

Shurjo Dighol Bari did. His signature is still something

that most of the new filmmakers crave to have in their

work. He often finds himself behind the camera. Though

he is not satisfied with the kind of shoddy equipment

he works with, his impression is clearly visible in

the end results.

As

for still photography, Anwar continues to record the

real with all its bites intact. "Abstraction works

only when it remains eloquent, when it strongly proposes

a concept," this seems like a motto to him. The

distanced look at life and the cultivated 'rarefied

taste' is not in his vein. For him everything harks

back to the reality that they came from. His word stand

for his work, "The purpose of art is not to please

or to beautify, but to transmit your own soul or thoughts

or conviction into the media you are working with,"

believes Anwar Hossain.

|

|

European

Rhapsody

European

Rhapsody Home-bound

Home-bound Looking

Back: The First Scene

Looking

Back: The First Scene The

scene had Joygun (Dolly Anwar) and Mymoon (Elora Gaohor),

her daughter, doing some chores in floodwater next to

the house. "The water was quickly receding and

we panicked," remembers Anwar. He was shooting

from the boat that was stabilised with four banana trees

propped up in the water. Anwar remembers his handsome

assistant cameraman in John Travolta-style garb and

hair in meticulous detail. "He had this very high

heeled black shoes on, Travolta type of course, and

he was a sight of incredible contrast. I was wondering

about how this person would be assisting me..."

says Anwar.

The

scene had Joygun (Dolly Anwar) and Mymoon (Elora Gaohor),

her daughter, doing some chores in floodwater next to

the house. "The water was quickly receding and

we panicked," remembers Anwar. He was shooting

from the boat that was stabilised with four banana trees

propped up in the water. Anwar remembers his handsome

assistant cameraman in John Travolta-style garb and

hair in meticulous detail. "He had this very high

heeled black shoes on, Travolta type of course, and

he was a sight of incredible contrast. I was wondering

about how this person would be assisting me..."

says Anwar.  From

the very beginning, everything went wrong. There were

six reflectors all together and Anwar wanted only one

for the two actresses, two for the ducks, one for the

mango tree and another for the sloppy riverside and

the last one was set to give the house and its bamboo

trees salience. His crew was shocked. "Everyone

was objecting to the fact that the actors had only one

reflector, never in their life did they see such a technique.

With few working in the field of cinema for the last

seven or ten years, and the assistant cameramen with

experience of ten or so prior projects, they were saying

that they never had this bitter experience of having

reflectors allocated for the surrounding objects,"

recalls Anwar.

From

the very beginning, everything went wrong. There were

six reflectors all together and Anwar wanted only one

for the two actresses, two for the ducks, one for the

mango tree and another for the sloppy riverside and

the last one was set to give the house and its bamboo

trees salience. His crew was shocked. "Everyone

was objecting to the fact that the actors had only one

reflector, never in their life did they see such a technique.

With few working in the field of cinema for the last

seven or ten years, and the assistant cameramen with

experience of ten or so prior projects, they were saying

that they never had this bitter experience of having

reflectors allocated for the surrounding objects,"

recalls Anwar.  Context

for Anwar has always been important. In fact in his

stills as well as in his cinematography, contextual

representation is what he so daringly achieves. In the

first shoot Anwar depended on the reflection of the

water too. Life in its truthfulness and natural phenomenon

are the two elements that always drove him. In the shooting

of the first scene of the historically important movie

that Shurjo Dighol Bari later became, the man behind

the camera took charge and transformed a bleak scenario

into an insightful observation of reality. Sheikh Niyamat

Ali, the director of the film, gave his cameraman full

support. Whatever Anwar proposed, he gave the green

light to it and it is this freedom with which Anwar

applied to his art. One must recall that the same man

who was so particular about using reflectors for the

whole scene, discarded their use while shooting the

scenes in the city in the same movie. "I wanted

to create a harshness that would be representative of

city life," said Anwar back in 2000 in an interview

with the Star Weekend Magazine.

Context

for Anwar has always been important. In fact in his

stills as well as in his cinematography, contextual

representation is what he so daringly achieves. In the

first shoot Anwar depended on the reflection of the

water too. Life in its truthfulness and natural phenomenon

are the two elements that always drove him. In the shooting

of the first scene of the historically important movie

that Shurjo Dighol Bari later became, the man behind

the camera took charge and transformed a bleak scenario

into an insightful observation of reality. Sheikh Niyamat

Ali, the director of the film, gave his cameraman full

support. Whatever Anwar proposed, he gave the green

light to it and it is this freedom with which Anwar

applied to his art. One must recall that the same man

who was so particular about using reflectors for the

whole scene, discarded their use while shooting the

scenes in the city in the same movie. "I wanted

to create a harshness that would be representative of

city life," said Anwar back in 2000 in an interview

with the Star Weekend Magazine. The

history of photography and cinematography in Bangladesh

did not remain the same since Anwar burst into the scene

in the sixties and masterfully turned the course of

cinematography in the 80s. Though Anwar regretfully

says, "It still remains the same," while referring

to the state of cinematography and the technical supports

involved in cinema in Bangladesh. As for still photography,

he is in great opposition to working project by project

with only mercenary motive in sight. "If you are

a creator you cannot create without falling in love.

Otherwise you should call yourself a businessman, not

a photographer or a cinematographer but a photo-businessman,"

stresses Anwar. Empathy with the subject and the medium,

for him, is the only assurance of artistic excellence.

The

history of photography and cinematography in Bangladesh

did not remain the same since Anwar burst into the scene

in the sixties and masterfully turned the course of

cinematography in the 80s. Though Anwar regretfully

says, "It still remains the same," while referring

to the state of cinematography and the technical supports

involved in cinema in Bangladesh. As for still photography,

he is in great opposition to working project by project

with only mercenary motive in sight. "If you are

a creator you cannot create without falling in love.

Otherwise you should call yourself a businessman, not

a photographer or a cinematographer but a photo-businessman,"

stresses Anwar. Empathy with the subject and the medium,

for him, is the only assurance of artistic excellence.

Down

Memory Lane

Down

Memory Lane Anwar

remembers how his name was often dropped from the list

of the registers though he was the first boy of his

class at the Armanitola Govt. High School. "Very

often the fees remained unpaid and though I used to

get scholarship for my position in class my name was

never mentioned during roll calling," reflects

Anwar.

Anwar

remembers how his name was often dropped from the list

of the registers though he was the first boy of his

class at the Armanitola Govt. High School. "Very

often the fees remained unpaid and though I used to

get scholarship for my position in class my name was

never mentioned during roll calling," reflects

Anwar. His

father, who was working as a manger at a local movie

studio, stood in his way. "It so happened that

despite the difficulties in life, and an enigmatic childhood

revolving around poverty and family obligations I stood

fifth in the SSC exam," Anwar recalls. In his family,

he was the first person to have completed the entrance

exam, which is equivalent to SSC. So the road to paint

and brush came to a close.

His

father, who was working as a manger at a local movie

studio, stood in his way. "It so happened that

despite the difficulties in life, and an enigmatic childhood

revolving around poverty and family obligations I stood

fifth in the SSC exam," Anwar recalls. In his family,

he was the first person to have completed the entrance

exam, which is equivalent to SSC. So the road to paint

and brush came to a close.  On

the Image Maker's Trail

On

the Image Maker's Trail The

eighth exposure of the first film that Anwar filled

in his newly bought camera was spent on a scene taken

from opposite Kamrangir Char. Anwar remembers how he

got down into knee-deep water to take the scene of dhopas

of Dhaka city. "This was the last exposure of that

eight exposure film, and this picture got me an award

in Bangladesh," Anwar goes back to his early start.

Golam Kashem Daddy used to run the Camera Recreation'?

Club, it was at the exhibition of the Club that he got

the award.

The

eighth exposure of the first film that Anwar filled

in his newly bought camera was spent on a scene taken

from opposite Kamrangir Char. Anwar remembers how he

got down into knee-deep water to take the scene of dhopas

of Dhaka city. "This was the last exposure of that

eight exposure film, and this picture got me an award

in Bangladesh," Anwar goes back to his early start.

Golam Kashem Daddy used to run the Camera Recreation'?

Club, it was at the exhibition of the Club that he got

the award.  "Ultimately

I ended up buying a better camera shared by four people,

buying an enlarger shared by four people, and buying

my first colour film at 36 Taka shared by four people,"

It was around the end of the sixties that Anwar got

his hands on his first colour film which they sent to

Germany to develop. "It was very exciting to get

my own first colour film from a photographer for the

army whom I used to call Alok Da, and to see the roll

when it came back from Germany," recalls the maestro.

"Till today colour slide development is not done

properly in Bangladesh, and this was in 1969,"

adds Anwar.

"Ultimately

I ended up buying a better camera shared by four people,

buying an enlarger shared by four people, and buying

my first colour film at 36 Taka shared by four people,"

It was around the end of the sixties that Anwar got

his hands on his first colour film which they sent to

Germany to develop. "It was very exciting to get

my own first colour film from a photographer for the

army whom I used to call Alok Da, and to see the roll

when it came back from Germany," recalls the maestro.

"Till today colour slide development is not done

properly in Bangladesh, and this was in 1969,"

adds Anwar. Anwar

remembers what slowly drew him to the movies. "It

was Khosru Bhai of Film Society and Badal Rahman who

pickled my young mind with ideas of exploring the reel,"

he recalls. The spectacles in movies amazed him. He

went on to study cinematography, heading for Pune in

1974 on an ICCR scholarship, causing resentment in the

family. He sat out on a journey that would later put

him in the path to greatness.

Anwar

remembers what slowly drew him to the movies. "It

was Khosru Bhai of Film Society and Badal Rahman who

pickled my young mind with ideas of exploring the reel,"

he recalls. The spectacles in movies amazed him. He

went on to study cinematography, heading for Pune in

1974 on an ICCR scholarship, causing resentment in the

family. He sat out on a journey that would later put

him in the path to greatness.  The

history of cinema in Bangladesh changed with that. Anwar

Hossain is a living legend now. The imprint of his skill

as well as his sensibility is now in demand. Though

not many films could provide him with the turf that

Shurjo Dighol Bari did. His signature is still something

that most of the new filmmakers crave to have in their

work. He often finds himself behind the camera. Though

he is not satisfied with the kind of shoddy equipment

he works with, his impression is clearly visible in

the end results.

The

history of cinema in Bangladesh changed with that. Anwar

Hossain is a living legend now. The imprint of his skill

as well as his sensibility is now in demand. Though

not many films could provide him with the turf that

Shurjo Dighol Bari did. His signature is still something

that most of the new filmmakers crave to have in their

work. He often finds himself behind the camera. Though

he is not satisfied with the kind of shoddy equipment

he works with, his impression is clearly visible in

the end results.