| Cover Story

GC Dev GC Dev

Philosopher, Scholar and Larger than Life Man

Syed Badrul Ahsan

Govindo Chandra Dev was the face of a generation we have lost to time. That is the tragedy. Equally tragic is the probability that we may never come across another like him. That last bit may sound like an exaggeration, but it is not. And it is not because Dev came of a generation that underpinned its reputation on a set of values, on morality that was taken as a base for behaviour. And as we celebrate the centenary of Dev's birth (he was born in 1907, which would make him a hundred and one years old today had he been around), it is a recapitulation of those values that works in our collective imagination. He was a philosopher, you might argue, which would be a perfect reason for him to uphold and nurture those values. Philosophers are forever doing that.

And yet you would be missing the point if you were to look upon GC Dev as the quintessential philosopher. He was that, of course, and he was a whole lot more. For his philosophy, his observations of life related, in a very literal sense, to the realities on the ground. Aloof from the multitudes he was not. And scholarly hauteur was in him a huge, healthy missing factor. He was pleased mightily when, on his expressing a desire for water to quench his thirst, someone passed a glass into his hand. 'What a hospitable girl!' He would say about the young woman proffering that glass to him. That is one of the ways in which Najma Yeasmeen, in the 1960s a pupil of Dev's and today an educationist, remembers the philosopher. Something of amusement was there as well, for in Dev resided an abundance of belief in the ability of people to do good. No, he was not naïve, he did not think that the world was perfection symbolised. But that individuals were possessed of the capacity to do good, indeed to uphold good at every turn was a belief that never abandoned him. It was in that comprehension of life that, unsuspecting, he opened his door to the men who were on a mission to kill him --- and everyone else like him. When the murderers in the form of the soldiers of the Pakistan army marched up to his residence on the Dhaka University campus in the early hours of March 26, 1971, they dispensed with civility as they tried kicking down his door. And they called out his name. The academic, ever the epitome of politeness and etiquette, opened it and told them he was the man they were looking for. Those soldiers did not waste time. The philistines that they were, and with the murder that was in their hearts, they shoved him on to his sofa and went about bayoneting and shooting him. The barbarians were at work. They dumped his body into the mass grave on the Jagannath Hall grounds, where the bones of his students and colleagues have meshed with his.

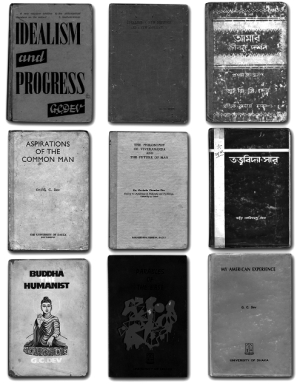

During his career Dr G.C. Dev published nine books, including two

in Bangla and seven in English. |

It was ironic that the suave man called GC Dev was finally done in by men to whom civilised behaviour did not matter at all. In the view of the state of Pakistan, in that moment of grave peril to Bangalis, the reputed philosopher was no more than a Hindu, a lesser being, a member of a religious community that could not have any place in the Islamic country that Pakistan had become and would mutate into something worse over the succeeding months. It did not matter to the army that Dev was an individual of national and global repute, that his pronouncements on philosophy had drawn the attention of people everywhere. What did matter was that, in the convoluted thinking that informed the state of Pakistan, Dev was a Hindu and therefore an enemy. It was a season when all Bangalis, because they refused to be conformists and refused to take things lying down, were a hostile force up in revolt against the communal state established through mayhem and murder in August 1947. In March 1971, therefore, it was a whole lot more than a Hindu in GC Dev that died. It was an illustrious Bangali whose life ended on a sudden note.

There was brilliance about Govindo Chandra Dev. Born in village Lauta of Sylhet district in 1907, he demonstrated early on a penchant for knowledge that would never let go of him as long as he lived. Something of the bohemian would always be part of the attitudinal in him, a certain propensity to inquire into the nature of things without in any way divorcing himself from the realities around him. He qualified in his Entrance examinations (a precursor of today's Secondary School Certificate examinations) from Beanibazar English High School with a first division in 1925. That was followed by an

Dev respected all religions; he would go to church on Christmas, to

the temple on Buddha Purnima and on Eid would take part in the

prayers and festivities. |

FA from Calcutta's Ripon College in 1927. In 1929, Dev obtained a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in philosophy from Sanskrit College; and in 1931 his academic career took another leap when he obtained a first class in MA in philosophy from Calcutta University. Thirteen years later, in 1944 (and this was a time when India's struggle for freedom from British colonial rule was gaining momentum), Dev came by a doctorate of philosophy from Calcutta University for his thesis Reason, Intuition and Reality. It may be noted that following his MA results, the upcoming philosopher spent a few years at the Research Institute in Bombay, where he engaged in research on Vedantic philosophy.

That was the beginning of what would turn out to be a comprehensive set of meditations on philosophy. Dev immersed himself in studies of Shri Ramkrishna, a clear sign of the comparative approach he was taking in his search for truth. But truth, again, was relative, which was why he saw little reason to keep himself confined to a particular strand in his experiments on thoughts. Philosophy for GC Dev was an endless exploration of the human experience inasmuch as it was an understanding of immediate realities. A common thread which bound the two was the secular spirit brought into an observation of them. The logical mind could not but be a significant first step toward enlightenment; and enlightenment was but another term for secular belief. Dev's psychological explorations consistently widened his expanse, to lead him to Spinoza, to Kant, indeed to the entire European philosophical ambience. But then came Dev's conviction that philosophy straddled continents, that it was not geography-specific, that indeed it held resonance everywhere. And, of course, there was ancient Indian wisdom to buttress his argument that philosophy underlined human existence at every turn.

Even as he moved into newer planes of philosophical thought, GC Dev pursued a teaching career that

Dev's adopted daughter Rokeya Begum, whose husband was also murdered by Pak Army in '71, along with her father. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

clearly acted as a testing ground for an exposition of his thoughts. He began lecturing at Calcutta's Surendranath College. When the college was moved to Dinajpur during the Second World War, he moved with it, to continue his teaching there. Surendranath College then moved back to Calcutta (and this was in 1945). This time Dev chose not to return to Calcutta but engaged himself in the task of giving shape to a new Surendranath College in Dinajpur. Careerism, as his attitude so amply demonstrated, was not for him. It was education, in fact a dissemination of the philosophical import of life that mattered. And it was such idealism that he carried with him as he made his way to Dhaka University as a lecturer in philosophy in 1953. And Dhaka University was the platform where Dev's teaching and his worldview would take a more definitive shape. By 1967 he had been promoted to the position of Professor in the Pepartment of Philosophy. And after that would come a year as Visiting Professor in distant Pennsylvania in the United States. That year must have been a gaining of fresh new ground for him, in much the same way that Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan had gathered new swathes of experience in his years as a philosopher abroad. By the time Dev returned home, he was ready to take the study of philosophy to newer dimensions. But in 1970 he travelled back to Pennsylvania. He was not to return and rejoin his department at Dhaka University until February 1971.

And those were stirring times. Rumblings of Bangali discontent were getting to be increasingly louder, to a point where the question of political sovereignty would begin to be considered by a people that had patently voted for nationalism at the December 1970 elections. By March 1971, with politics at its most assertive and with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in clear charge of what would soon be a free country, GC Dev marched with the millions on the streets of Dhaka. Philosophy and politics thus found a point of convergence in him. He was not willing to stay aloof or away from the national struggle for self-expression but be part of it. Like so many others who would suffer for their politics, GC Dev at that point became a marked man. The state of Pakistan would keep its sights on him and eventually pounce on him only moments into the genocide it would inaugurate on March 25, 1971.

A secular GC Dev had little in common with the communal structure that Pakistan was to be. Yet his philosophy kept him going, perhaps in the belief that someday the insular nature of the state would undergo transformation. As events were to demonstrate only too well, Pakistan would only manifest its uglier sides, all of which were to reach a climactic stage with the beginning of the genocide. Dev's lectures on philosophy as a core principle in life, delivered in the two wings of Pakistan, would not ultimately matter in a state intent on overturning an electoral result and following it up by a systematic, organised murder of its own people. And there lay the contradiction. In the land of philistines, GC Dev was on a mission to sublimate thoughts --- in politics, in education, in overall social outlook --- to a level of unfettered liberality. But perhaps by March 1971, as the political struggle against Pakistan gathered steam in its eastern province, Dev knew that Pakistan was not the land for liberalism. In this, he joined millions of other Bangalis in forging the belief that a new promise, in the form and spirit of a free republic of Bangladesh, beckoned on the horizon. Having gone through the searing pain of the partition of India, GC Dev was now ready to witness the rise of a secular Bangladesh, a state that would be home to all the ideals he had espoused all his life.

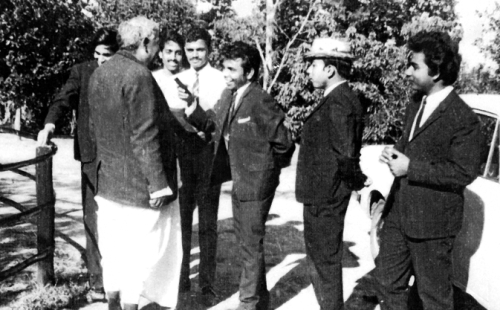

With his 1970 batch after their Honours exams in 1969.

But life for Dev would end suddenly and traumatically. On that night of horror in March 1971, thousands of others --- and among them were his university friends and colleagues and students --- would be mown down. Those killings must surely rank as some of the more sinister aspects of character in the state that went out on a mission to murder men and women intent on reclaiming democracy for themselves.

|

| At a birthday celebration with family and friends. The celebration of his illustrious life continues… |

|

| Accessible, charming and always full of new ideas, his students were constantly eager to interact with their remarkable teacher. Here, at a picnic with his 1970-71 batch. |

Govindo Chandra Dev did not marry although he did adopt a son and daughter. But the children he saw around him drew from him all those paternalistic instincts that make illustrious beings of men. He would laugh; and the arrival of a visitor would quickly light up his world as he welcomed his guest. The little things of life took his fancy; and big ideas were the canvas he played on. Najma Yeasmeen remembers. In the early 1960s, as Dr. Ghulam Jilani finished his tenure in the department of philosophy and prepared to return to his native West Pakistan, he told his students: 'Professor GC Dev is not only a heavyweight in body but also in brains . . . I leave you in very good hands.” That was how Dev was celebrated in his times.

GC Dev, it is comfortable to think, was larger than life. In death, and more than a century after his birth, he remains a potent symbol of human hope, of the basic decency that defines human character.

With his adopted son and daughter-in-law (top left); With daughter-in-law Purabi Dutta (right); Sharing a light-hearted moment with his students (1970 batch) at a picnic (bottom left)

Photographs courtesy of Department of Philosophy , Alumni Association, Dhaka University.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |