On

right to freedom of religion and the plight of Ahmadiyas

Ridwanul

Hoque

The

recent governmental action banning publications of the Ahmediyas (or

Ahmadis) must have shaken the conscience of those who believe in democracy,

peace and justice. The action has sparked off huge debates and justifiably

severe criticisms. A legal challenge of the government's order has already

reached the court of justice. This short article purports to explore

some legal aspects of the governmental action with reference to Pakistani

situation where the same issue has caused a lot of problems..

Ahmadiyas, sometimes

called Quadianis, claim themselves as Hanafi Muslims but do not believe

in the finality of Islam's Prophet - Mohammad (SM). Resultantly, they

have been facing rivalries and oppositions across the world, although

Pakistan is the only state to have declared the Ahmadis as non-Muslims.

In Bangladesh and India, there is no legislation that goes to the extent

of declaring Ahmadiyas non-Muslims or even limiting their activities.

Nor is there any law that defines who is or not a Muslim. In India,

the issue of Ahmadis came into forefront in the seventies. On one occasion,

the court very pragmatically held that the Ahmadis are Muslims [Shibauddin

Koya AIR (1971) Ker. 206].

In Pakistan, Ahmadis

have been declared as nonMuslims and their freedom of religion curtailed

by a whole series of ordinances, acts and even constitutional amendments.

This was concomitant with the process of Islamisation of Pakistani legal

system orchestrated largely by General Zia-ul Haq. Following a constitutional

definition of 'Muslims' in 1974 that indirectly excluded the Ahmadis,

a law-suit was brought seeking injunction to prevent Ahmadis from observing

Islamic practices. But the court declined to act and Ahmadis were allowed

to maintain mosques and to call for azans. Things changed gradually.

Besides being declared as non-Muslims, activities of Ahmadis were made

an offence by an Ordinance of 1984. Notably, within the process of Islamisation

of Pakistani legal system, Shariah Courts were created to review compatibility

of any law with the 'Injunctions of Islam'. On the other hand, there

were Constitutionally guaranteed fundamental human rights (e.g., freedom

of religion, protection of minorities etc) which also created a basis

of judicial review. The Ahmadis went to the Shariat Court to unsuccessfully

challenge the authencity of the 1984 Ordinance. The challenge was aborted

as the court held that the Ordinance was not un-Islamic. (Mujibur Rahman,

PLD 1985 FSC 8). On another occasion, the court held that Muslims and

Ahmadis are two separate and distinct entities (Khurshid Ahmad, PLD

1992 SC 522). These judgments left the Ahmadis effectively insecure

and observance of their religious activities still remained a criminal

offence. Having lost the legal battle of sustaining their religious

rights, the community went to the Supreme Court to challenge the 1984

Ordinance on the ground of constitutionality. (Zaheer-ud-din, 1993 SCMR

1718). Not surprisingly, the court interpreted the right to freedom

of religion from the perspective of an Islamic state's obligation to

promote and preserve the state religion, i.e., Islam. Consequently,

the Court decided by a majority that the Ordinance was not unconstitutional,

thereby throwing the Ahmadis into an apparently perpetuating state of

insecurity and frustration. It seems that the court's unduly restricted

interpretation of 'freedom of religion' was much influenced by the Pakistani

politics of that time. Labeling the Ahmadis as 'non-Muslim minority',

the Court held: "The freedom of religion is guaranteed by Article

20 .... The overriding limitation .... is the law, public order and

morality. The law cannot override Article 20 but has to protect the

freedom of religion without transgressing bounds of morality and public

order. Propagation of religion by the appellants (Ahmadis) who as distinguished

from other minorities, having different background and history, may

be restricted to maintain public order and morality.''

Right to freedom

of religion is a very special kind of fundamental right which touches

a person's belief as to his creation, life and death as well as his

way of life and thinking. Interaction with religion and the state has

been therefore inevitably critical and intriguing and maintaining a

peaceful atmosphere between different believers of the same or different

religions has emerged as a potentially difficult job for the state.

A strategy of attaining that objective of peace is by resorting to the

state principle of secularism or by adhering to the principle of ensuring

human rights for all ethnic, social and religious minorities. But secularism

is not always an ideal solution to the problems with freedom of religion,

unless there is democratic political will. An examination of the developments

in this field in India reveals that freedom of religion is not absolute

even in a secular state. And, from the Pakistan's experiences as above,

we have learnt that interpretation of freedom of religion in a religious

state brings forth a further dimension to the judicial discourse.

Truly speaking,

as regards legal and political difficulties ensuing from the interpretation

of the right to freedom of religion, Bangladesh does not fit into the

systemic position of either Pakistan or India. Although Bangladesh initially

adopted secularism as one of its core fundamental principles of state

policy, she has abandoned the principle later, following, of course,

not a truly democratic process. On the contrary, it is not a Islamic

state either. Nor is its legal system Islamised, although Islam has

been made 'state religion' by amending the Constitution through another

undemocratic means. Bangladesh is a democratic, plural society with

a record of fairly peaceful coexistence of a diverse number of religious,

ethnic or linguistic minorities. Its Constitution is a unique piece

of supreme legal document encompassing almost all human rights. The

Constitution has unequivocally and emphatically insisted on democracy,

rule of law and social, economic and political justice. Needless to

say, the level of democracy or civility of a society is measured in

terms of its record of preserving and promoting fundamental human rights

of all including minorities without any sort of discrimination.

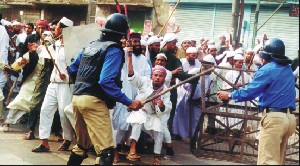

Fighting

for freedom of religion!

Article

39 (1) of the Constitution guarantees freedom of thought and conscience.

Interestingly, unlike freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by

Art. 39 (2), this right has not been subjected to any legal restrictions.

Correspondingly, the threshold of the government's obligation not to

interfere with the citizens' freedom of thought is high. Prohibition

by government of Ahmadiyan publications is undoubtedly a severe blow

on the community's freedom of thought. More importantly, the banning

order has violated the community's right to freedom of religion. Article

41 of the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, albeit subject

to 'law, public order and morality'. However, it is a cardinal principle

of constitutional jurisprudence that 'public order and morality' ground

does not authorise the parliament to take away the very right to freedom

of religion. That said, it should also be noted that law does not also

allow any one to impede social order or to jeopardise public morality.

What is tricky is that government does often play politics with 'public

order and morality' ground as this has not been defined in the Constitution

or any other law. Absent such a definition, it is a challenge for the

courts to determine what 'public order and morality' means in a given

situation. Thus when a governmental action is alleged to have violated

freedom of religion of a person or people and the government advances

the ground as justification, the court has to make a balancing exercise

keeping in mind that the concept of public order and morality is not

static, rather society-specific.

A pertinent question,

therefore, is whether Ahmadiyan activities are against public order

and morality justifying the government's action. As we have seen above,

in Pakistan, the activities of the Ahmadis were legally prohibited and

they were declared non-Muslim on the ground of public order and morality.

But the situations - legal, political and constitutional - in Pakistan

are clearly not the same as in Bangladesh. We have seen that present

constitutional scheme disallows the type of action the government has

taken. One might however argue that there are at least two potential

elements that might liken the situations to those of Pakistan. These

are: (i) that the principle of absolute trust and faith in the Almighty

Allah is a fundamental principle of the Constitution and state policy

and (ii) that Islam is the state religion of Bangladesh. A closer look

at these previsions will show that attack on Ahmadis' freedom of religion

cannot be justified with reference to these provisions. Because, true

faith in Islam requires us to show tolerance to others who expresses

different opinions and even to those who oppose Islam. That Islam itself

acknowledges various sects is particularly educative for us. State religion

provision of the Constitution does not permit the state, it is argued,

to lay unreasonable restrictions on Ahmadis' freedom of religion, because

the provision does not obligate the state to do anything in relation

to state religion. This is merely a recognising or declaratory provision.

Another potential argument in defence of the governmental action might

be that government did not actually prohibit the Ahmadis' activities,

nor were they declared non-Muslims and thus their right to freedom of

religion is kept untouched. Instead, it has only forfeited some of the

Ahmadiyan publications on the ground that these did hurt the belief

of general of Muslims. As said earlier, regulation of religious activities

may be justified on the ground of public order (Jibendra Kishore, 9

DLR (SC) 21). The 'public order' ground must, however, be exercised

bona fide and objectively. In Bangladesh Anjuman-E-Ahmediya (45 DLR

185), the court upheld the forfeiture of a book as it outraged the religious

belief of bulk of Muslims. But now the government seems to have forfeited

the Ahmadiyan books on a wholesale basis and seemingly to console those

who are demanding the complete prohibition of practising Ahmadiyanism.

Thus at any rate,

governmental action in question appears to be blatantly illegal and

incompatible with its constitutional duty to preserve and promote human

rights for all.

Ridwanul

Hoque is an Assistant Professor, Department of Law, Chittagong University.