Let our champion women power Bangladesh forward

As much as winning the South Asian Football Federation (SAFF) championship, it was the 23-1 winning margin of the Bangladesh women's football team that was truly breathtaking. Such a lopsided score in five matches spoke of grit, energy, hunger, motivation, and sheer dauntlessness.

In a larger sense, this overwhelming score, and the championship, speak of the spirit of Bangladeshi women ready to power the country forward.

Women's empowerment – a gift of liberation – has already been a significant force behind development. After independence, women became more educated, rapidly achieving parity with men in primary and secondary education enrolment, aided by female teachers who comprise 61 percent of primary school teachers.

Women also used their reproductive rights under a proactive family planning programme to increase contraceptive use from eight percent at independence to over 62 percent, leading to a decline in the annual population growth to about 1.1 percent and an increase in their life expectancy to 74 years, three years more than men. The slowing population growth was vital in raising per capita incomes and reducing congestion in our densely populated country.

Women became economically active as workers and entrepreneurs. Micro-finance programmes of Grameen Bank, Brac, and the PKSF helped women become entrepreneurs, their numbers quadrupling and creating nearly half a million women-led non-agricultural enterprises. The rapidly growing export-oriented garments industry employed several million female workers. Bangladesh's female labour force participation rate thus now stands at 35 percent, significantly higher than in India or Pakistan.

However, as in most spheres where Bangladesh has also made noteworthy progress, there is still a considerable distance to go in empowering women.

First, let us be clear about its necessity. Women's agency is important in itself. But it is also a fact that there has not been, and cannot be, any development to upper-middle and higher-income ranks without the enthusiastic participation of women. All advanced economies and societies (measured by income and social progress indices) – such as Norway, Sweden, Germany, Canada, the United States, Japan and Korea – rank among the top 10 percent of countries in the gender development index of the UN. Conversely, the 10 percent of countries that rank at the bottom are also the world's poorest.

But how do we know what is the cause and what is the effect? Could economic growth development lead to women's empowerment rather than the converse? Income growth of women indeed increases their ability to make decisions about their own and their families' welfare.

However, economics and evidence suggest that while causation goes both ways, the dominant direction is that women's empowerment leads to growth and social development.

First, let us consider the case of resource-rich countries, as in the Middle East, with high per capita incomes but limited women's empowerment. Their riches have not empowered women. On the other hand, every country that has grown rich without the benefit of oil and mineral resources has empowered women. These women make decisions about their lives and own assets, enjoy freedom of movement, including the ability to leave their marriage, and have protection against violence.

The inference is that women need agency for countries without bountiful natural resources to grow. But why is that so? For at least three reasons.

The first is the sheer arithmetic of national income, which is the multiple of persons employed times their productivity. In the case of Bangladesh, if women participated in the labour force at the same rate as Vietnam, i.e. at 69.6 percent rather than 34.9 percent, and produced with average labour productivity, our national income would jump by a whopping 27 percent in real terms. And that would mean that over five years, our national income would be more than 70 percent higher than it would be otherwise, because of the increased participation of women in work. The sheer size of this compounded impact suggests that significantly increasing women's participation will be essential to achieving our national goals of attaining upper-middle-income and higher-income statuses.

The second reason is more profound and long-term. Both research and our intuition suggest that empowered women create healthier, more educated families. One wishes there was more research on this in Bangladesh. However, evidence from other lower and middle-income countries show that when mothers are empowered to make decisions, children's early childhood development and cognitive scores in numeracy and literacy are significantly higher. The message is clear. If we want healthier and more intelligent and productive future citizens, we must give women agency.

Third, we also know about the importance of women's empowerment in driving development through an unfortunate counterexample. In some countries, rising incomes can initially lead to the disempowerment of women. In India, for instance, a marked decline in women's work has accompanied rising per capita incomes. While several factors are driving this, a key one is that as income rises, families opt to keep their women home, ostensibly to take care of children and perhaps as a display of status.

The implication is there must be proactive government policies and social campaigns to encourage women to be educated and work to combat this tendency. These policies need to include providing good childcare facilities.

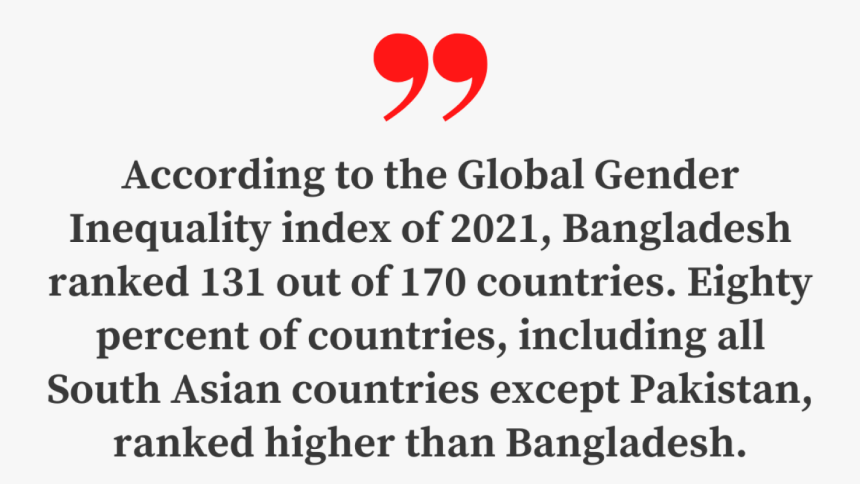

Where lies Bangladesh in empowering women? Unfortunately, it lies in contrast to the spirit of our championship-winning women's football team and the legacy of millions of women workers in agriculture and the RMG sectors, as well as entrepreneurs. According to the Global Gender Inequality index of 2021, Bangladesh ranked 131 out of 170 countries. Eighty percent of countries, including all South Asian countries except Pakistan, ranked higher than Bangladesh. Let us unpack this index to see why Bangladesh does poorly despite noteworthy progress in women's empowerment.

Bangladesh performs poorly because of high maternal mortality (173 in 100,000 live births) and adolescent (ages 15-19) birth rate of 76 per 1,000 women. Both India and, surprisingly, Pakistan do better than Bangladesh. Only Nepal ranks the same in South Asia, doing slightly worse in maternal mortality and better in adolescent childbirth. On average, East Asian countries do far better, with a maternal mortality rate of 82 and an adolescent birth rate of 22.

Bangladesh does better than other South Asian countries, except Sri Lanka, regarding education. More than half of the female population has had some secondary education compared to about 40 percent of the South Asian average. However, this better outcome provides cold comfort compared to East Asian countries, where more than 70 percent of females had some secondary education on average. Similarly, while Bangladeshi women have had 6.8 years of schooling on average, higher than the South Asian average, it lags behind the 8 years of schooling for Vietnamese women.

While there are other factors, early child marriage is the common ailment causing adolescent birth rates and high maternal mortality rates in Bangladesh as well as lower years of schooling. Alarmingly, more than half of Bangladeshi women aged 20-24 were married before 18, while 13 million were married before the age of 15.

In addition to measures against child marriage, we need to provide opportunities to enable women to pursue education and work and avoid early marriage. Take, for instance, the high dropout of girls while pursuing secondary education. Evidence suggests that the lack of proper sanitation facilities, including for menstrual care for female students, is a significant cause of high dropout rates. On the other hand, research has also shown that when women are hopeful of getting employed by garments factories, they tend to delay marriage and get more schooling.

Another factor that constrains women's agency is unequal access to credit. Only about one-third of women can access credit as opposed to two-thirds of men. Even in the case of micro-credit, research suggests that while 91 percent of micro-credit customers are women, male family members often utilise the funds.

Due to early marriage, unequal education facilities, and lower access to credit, women's empowerment suffers from the significant difference in earnings between men and women. On average, women's per capita income is USD 2,811 against USD 8,176 for men (adjusted for purchasing power parity).

The critical task for empowering women must be a vigorous implementation of existing government policies that discourage marriage before 18 for women. Although the National Action Plan to reduce child marriage by half involves 25 government ministries, only about one percent of the government's budget goes to the main implementing agency. Despite laws, news reports suggest that child marriages take place with impunity.

But the desired outcome will not come from laws alone. We also require a countrywide social campaign and media blitz led by political, cultural, social, and religious leaders. This campaign would be like the highly effective barrage of birth control messages and ads that came through radio and television in Bangladesh's first decades. Early marriage must have the same stigma and be as expensive as large families. Bangladesh will then have taken an essential step to become a country of champion women.

Dr Ahmad Ahsan is the director of the Policy Research Institute (PRI) of Bangladesh and a former World Bank economist and Dhaka University faculty member. Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments