America, Grassroots Activism and the Creation of Bangladesh

Henry Kissinger once wrote that "history is the memory of states". In this vision of the past, it is the decision-makers and occupants of the seats of political power whose thoughts and feelings matter. This, in my view, is a myopic vision of history. The memories of a state are not enough to understand the past. They exclude the powerful, everyday stories of ordinary people.

As historian Howard Zinn wrote: "If history is to be creative, to anticipate a possible future without denying the past, it should...emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even if in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together, occasionally, to win."

It is this spirit that animates my recently published book, An Internal Matter: the United States, Grassroots Activism, and the Creation of Bangladesh (UPL, 2021), which draws upon new interviews and previously unexamined archival materials to chart the efforts of hundreds of American activists who supported Bangladesh's cause in 1971. To glimpse this spirit in practice - consider the following two perspectives.

In May,1971, the scholar Mary Frances Dunham sat down at her home on New York's Upper East Side to write a letter to the First Lady of the United States. Her reason for writing, she explained, was the ongoing crisis in Bangladesh where for the past two months the forces of Pakistan's military government had been attempting to suppress the widely supported Bengali movement for self-determination. Advising Mrs. Nixon that American support for Pakistan was fuelling the suffering of millions, Mary Frances wrote:

"Like funerals, the recent disasters in East Pakistan (the cyclone and revolution) have brought together Americans who once lived and worked there. We are deeply concerned that our country not repeat past mistakes and that we act more wisely and more firmly than we have in the past in view of the present tragedy.

Widely scattered geographically, informally silenced by organizations for whom we work, it has been especially difficult to make ourselves heard. Yet we have insights and information which only persons who have lived for some length of time in Bengal can have. We are educated and intelligent Americans, former employees of the US Government, of international agencies, of a wide variety of missions, private foundations and companies—professors, doctors, specialists.

We who have lived there have witnessed the chronic misunderstanding between the West and East Pakistanis and the oversimplified aid pattern from America which only encouraged an economic rift between them. We were not heeded in Pakistan, and we desperately want to be heeded now. The lives of many million[s] [of] people and one of the world's richest cultures hang in the balance."

For Mary Frances, who along with her family had lived in Dhaka from 1960-67, the tragic conflict in East Pakistan was anything but remote. It cut to the core of America's role in the world. Singling out the influence of continued US economic and military assistance to Pakistan and the dangers of short-term political thinking, she impressed upon Mrs. Nixon the importance of allowing Americans with an intimate knowledge of East Pakistan to be heard: "without wisdom [American] generosity will be misused again."

Around the same time, on the other side of the country in Glendale, California, a group of Bengali students and professionals, the American League of Bangladesh (A.L.B.), issued a missive to local newspapers, also calling for the US to rethink its support for Pakistan:

"The struggle that is now going on in Bangladesh is part of the general world-wide movement for liberation from colonial domination. It is no different from the struggle that the American people waged against their distant rulers two centuries ago.

Like the British colonies in America, East Pakistan is being bled white in the interests of alien rulers a thousand miles away. Like you, we are having to pay taxes to a distant government indifferent to our welfare, without any right of representation. Like you, we have decided to exercise our right of self-determination. Like you, we will prevail, no matter the cost.

Knowing the great traditions of the American people, the people of Bangladesh have no doubt that the American government and people will do their best to arrest the monstrous genocide in Bangladesh.

Time, however, is of essence. If innocent human beings have to be saved, the time for action is now. In the name of humanity, we appeal to you to use your influence as a world power to stop the indiscriminate killing of thousands of innocent civilians."

Two pleas—one to perhaps the most powerful woman in the country, the other to the American people at large. United in their concern for a conflict that drew comparatively little attention from most Americans compared with the more pressing Vietnam War, the words of Mary Frances Dunham and the A.L.B. offer a glimpse into the grassroots response and activism that the conflict in Bangladesh provoked in the USA.

While many activists fought to help create Bangladesh, a new country that would be free from what they saw as decades of Pakistani tyranny, others were more concerned with the damage that US support for Pakistan would do to America's reputation abroad and for the stability of South Asia. Yet the stories of such activists, the many Bengalis and Americans who spoke out for Bangladesh and against US policy in 1971, remain relatively hidden in existing histories of the war.

What bound all activists who mobilised in America during the Bangladesh crisis was a deep sense that the crisis occurring thousands of miles away in East Pakistan was layered in injustices. The injustice of the democratic aspirations and rights of a people being stifled by a military dictatorship, the injustice of seeing their friends and families driven from their homes by military force, and the injustice that moved the Nixon administration (and numerous other governments) to treat such acts of violence and genocide as "an internal matter" for Pakistan. For these activists, the East Pakistan crisis was not some small feature of internal Pakistani politics, but was, rather, a matter for all humankind and something which compelled those who opposed militarism and genocide to speak out.

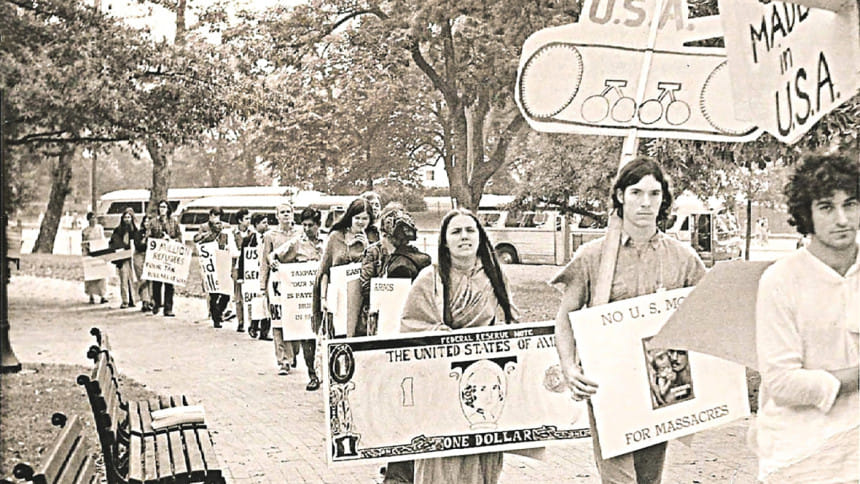

Motivated by these injustices, throughout the nine months of the war, activists mobilised across America to raise awareness about the struggle in Bangladesh and press American lawmakers to challenge the Nixon administration's continued support for Pakistan. Initial efforts in the wake of Operation Searchlight focused on channeling first-hand information from Bangladesh to the halls of power in Washington.

This concerted lobbying effort saw Bengalis and Americans working together to provide sympathetic politicians with an alternative picture of what the US State Department dismissed as "an internal matter" for Pakistan -- one in which American economic and military assistance was actively fuelling the brutal repression of Bengali nationalism and damaging America's reputation around the world. Encouraging lawmakers to support legislation that would cut off all aid to the Pakistani regime was the primary aim of many such grassroots lobbyists.

What transformed the crisis in Bangladesh from yet another far-away conflict that Americans could ignore into something that attracted major humanitarian concern, however, was the flight of millions of refugees into India throughout the summer. Indeed, Indira Gandhi said in mid-1971 that, due to the "cruel tragedy" unfolding in "Bangla Desh," the refugee crisis could no longer be treated as an "internal problem" for Pakistan, arguing instead that it was both "an Indian problem" and a "world-wide problem" which threatened the peace and security of the entire region.

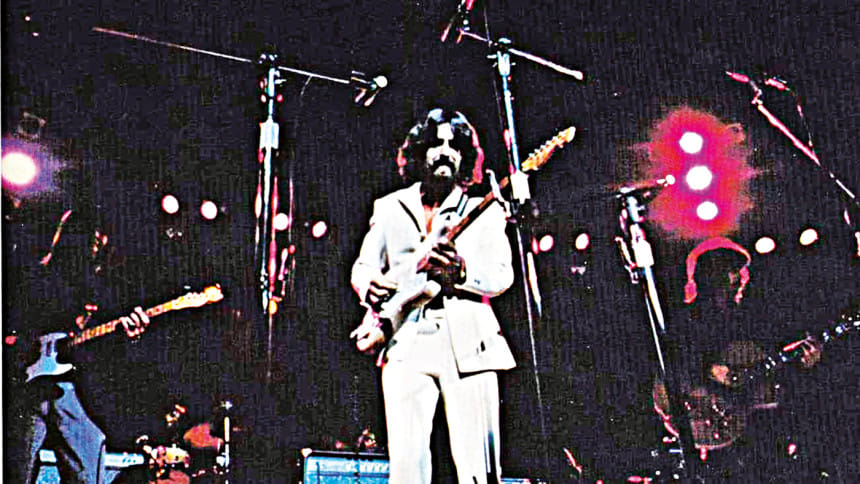

Again, grassroots activists played an important role in making the plight of Bengali refugees known to the American public and to US lawmakers who could try to influence foreign policy. As had occurred during the Nigeria-Biafra crisis in the late 1960s, refugees emerged as physical objects of humanitarian concern (they were far less abstract than sterile debates about foreign assistance legislation), inducing a host of different activists to raise awareness and funds for refugee relief. Accordingly, the summer of 1971 witnessed major rallies (including the Concert for Bangladesh), advertising campaigns and editorial wars in newspapers between Bangladeshi and Pakistani activists, and substantial fundraising activities. The visits of US politicians to refugee camps were also particularly helpful to activists' efforts. In June, for example, Cornelius Gallagher became the first high profile US congressman to visit India and tour the refugee camps near Kolkata, saying that "after meeting some of the evacuees I am now convinced that terrorism, barbarities and genocide of no small magnitude have been committed in East Bengal."

The final months of the war saw a renewed focus on activists supporting the passage of legislation that would cut off aid to Pakistan as they sensed that Bangladesh was quickly shifting from being an idea and a slogan into a reality. The assistance of a delegation of diplomats from Bangladesh's government-in-exile in Washington and at the UN in New York helped very much in making the country's case to other nations. In the event, however, the birth of Bangladesh came before the new laws, which activists had spent thousands of hours raising awareness about and supporting, could come into effect. This was far from failure, however, and many rightly felt that their efforts to keep the American public and senior politicians informed throughout the conflict had made an important difference in pressuring the US (and ultimately other nations) to soften their support for Pakistan, thereby supporting Bangladesh's victory.

The foregoing passages should indicate the range and depth of actions that characterised American activists' efforts during the creation of Bangladesh. But what next for histories of the Liberation War overseas? In my view, as a new generation of Bangladeshi scholars takes up the task of understanding the defining event in their country's past and ever greater numbers of foreign scholars "discover" the Liberation War, it is incumbent upon historians to do more than simply compile documents and reprise well-worn statements like "Nixon and Kissinger were against us, but the American people were with us." What is needed is a much greater focus on integrating the story of the Liberation War into broader histories of the post-Second World War period and positioning it in conversation with other comparable conflicts to understand how international society responded (or failed to respond) to such emergencies.

Here, several other opportunities also come to mind. First, there is a pressing need to examine the non-governmental side of the conflict in greater depth and use such organisations' archival collections, which are invariably located abroad and which historians have largely ignored. The archives of Oxfam and CARE in Oxford and New York, respectively, are rich with materials relating to 1971, but remain relatively unexamined. Scholars must access and traverse these materials, asking how humanitarian NGOs, development organisations, and international institutions responded to the Liberation War and shaped the process of post-war reconstruction.

Moreover, the tendency that Srinath Raghavan notes in his global history of 1971 to temporally extract the war from all its surrounding contexts except the inevitable march of Bengali nationalism has a stifling effect on the ways in which historians can envision the Liberation War. Attempting to view the cyclone, the war, and immediate period of reconstruction as a single, interconnected whole would, I feel, have a positive effect on the range of stories that historians can tell about the conflict.

In any event, although historians have hitherto paid them little attention, the activists who mobilised for Bangladesh in America during the Liberation War cannot forget the events of 1971 and nor should we. From sewing Bangladeshi flags in living rooms to briefing the highest officials in Congress and the World Bank. From carrying guitars at the Concert for Bangladesh to editing speeches for Edward Kennedy. From the invisible labour of private lobbying to inescapably visible statements of protest: people fasting in front of the White House in mock "sewer pipes" like Bengali refugees, activists in canoes trying to block Pakistani ships from docking to collect US made weapons, and marches through the streets of New York. Each action and each activist, motivated as they were by a profound sense of injustice at the events in Bangladesh and the US government's callous response, contributed in their small way to the struggle for and the creation of Bangladesh.

Samuel Jaffe is an independent scholar based in New Zealand. He holds a dual MA/MSc in International and World History from Columbia University and the London School of Economics. "An Internal Matter": The United States, Grassroots Activism and the Creation of Bangladesh is his first monograph and is available to be purchased via UPL, Amazon and Rokomari.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments