Restoring Tajuddin in history

The idea of Bangladesh's parliamentary democracy being short-changed to a one-party system was anathema to Tajuddin Ahmad. He warned Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in the weeks before the Fourth Amendment to the constitution was adopted by the Jatiyo Sangsad, that the move would be a negation of all that the two men and their party, the Awami League, had long struggled for. Of course, Tajuddin's warning was not heeded.

And that warning came from Bangladesh's first prime minister at a time when he was fast being pushed into irrelevance in a party he had, together with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, built up patiently and assiduously as the foremost Bengali political organization over the decades. Tajuddin Ahmad, self-trained in the best of liberal-cum-socialist political traditions, remained acutely aware of the dangers the country was being pushed into through the encroachment of illiberalism in national politics. That is the truth we have always known and which truth has now been brought forcefully into the public domain by Sharmin Ahmad, to the discomfiture of many in the Awami League and certainly in the government it runs in these present times. The writer, eldest child of Tajuddin Ahmad, ought not to expect, indeed does not expect, her work to be welcomed by those who have over the decades sought strenuously to undermine the man who determined, in the early hours of the genocide launched by the Pakistan army in late March 1971, that the challenge could not go unanswered. Convinced that Bangabandhu was not agreeable to leaving his home and eventually leading the resistance --- Bangabandhu's reasons, in the light of history, were justified given that as the elected leader of the majority party in the Pakistan national assembly he could not be expected to flee --- it was for Tajuddin Ahmad to shape the military struggle he saw as an inevitability. And he did the job with finesse and sagacity.

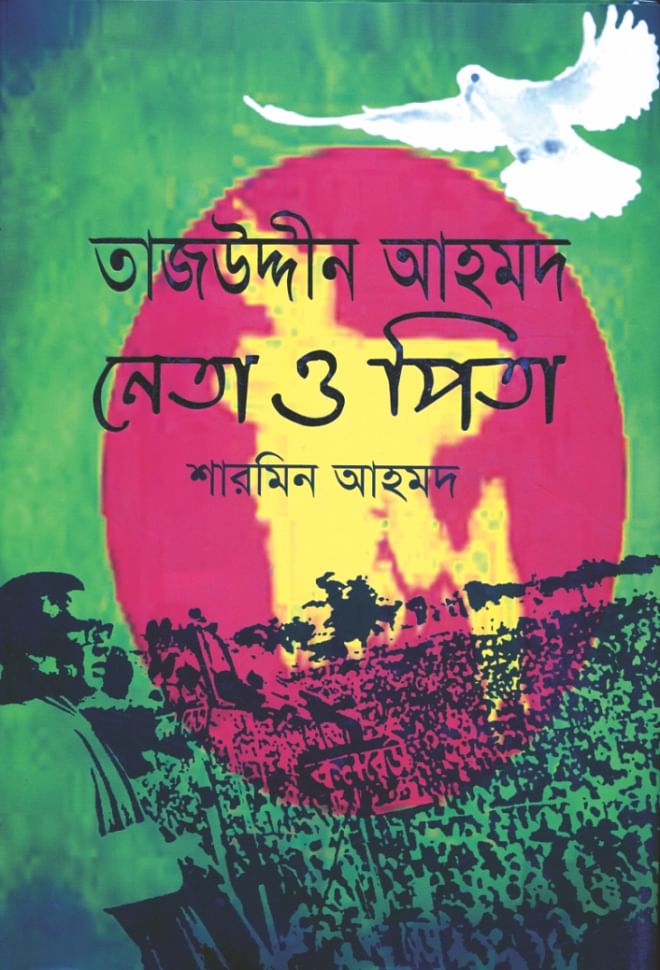

From a historical point of view, Neta O Pita is a necessary reappraisal of Bangladesh's history in the formative years of the movement for regional autonomy that Mujib and Tajuddin together forged and waged till the collapse of the political negotiations involving the Awami League, the Pakistan People's Party and the Yahya Khan junta in March 1971. Then comes the question of the armed struggle that the Mujbnagar government --- and Mujibnagar was a term coined by Tajuddin --- initiated and waged over the nine months of Pakistan's military occupation of Bangladesh. On another and unquestionably crucial plane, Sharmin Ahmad examines the complex relationship between Bangabandhu and Tajuddin Ahmad, the complexity of course coming into the picture soon after the liberation of the country and Mujib's return to Bangladesh from incarceration in Pakistan. At a third level, it may well be argued that the writer is keen that her father's place in history be set right, which is again quite natural. Sharmin Ahmad believes, and there are many others who share her view, that Tajuddin Ahmad has been turned into a footnote in Bangladesh's liberation story. Her key argument revolves around a huge gap she brings into focus before her readers, namely, that there is a straight leap from the March 1971 to January 1972 in the Bangladesh narrative, that indeed there is hardly any detailed account of the guerrilla war Tajuddin Ahmad conceived and carried to fruition in December 1971.

But nowhere does the writer attempt to place Tajuddin as a rival to Bangabandhu. The ties between the two men, it is obvious from Ahmad's telling of the tale, remained more or less intact, even after Tajuddin was compelled to leave government. From an absolutely historical perspective, the biggest damage done to the country in the early 1970s was the rift that led to Tajuddin's departure from the government. The absence of Tajuddin's steady hand on the state, combined with his intellectual brilliance and political acumen, was only to hasten the collapse of a government where sycophants, in the form of rightwingers like Khondokar Moshtaque and inveterate anti-Tajuddin elements like Sheikh Fazlul Haq Moni, found it easy to exercise influence on the machinery of the state. Politically, Tajuddin Ahmad was being pushed, even after his resignation from the government in October 1974, into being a historical non-entity. On the fourth anniversary of the Mujibnagar government in April 1975, when every other member of the 1971 administration travelled to Mujibnagar to commemorate the event, Tajuddin Ahmad was studiously ignored. The man who clearly was the leading force behind the formation of the Mujibnagar government was not invited to Mujibnagar. He spent the day in depression at home in Dhanmondi.

And yet Tajuddin's loyalty to Bangabandhu never wavered. Towards the end of July 1975, armed with information that a plot was on to murder the Father of the Nation, he turned up at 32 Dhanmondi to warn his leader of the impending danger. Bangabandhu, as was his wont, was dismissive of the threat. Tragedy overtook the country barely a fortnight later. Sharmin Ahmad makes it a point, though, to re-emphasise the closeness Mujib and Tajuddin continued to enjoy. On a day in July 1975, days after Sheikh Kamal's marriage to the sportswoman Sultana had taken place, Bangabandhu telephoned Tajuddin to inform him that Sheikh Jamal's marriage too had been finalized, with Bangabandhu's niece. Throughout the narrative, the writer notes the long, cordial relations the two families maintained through the political movement Bangabandhu and Tajuddin waged against Pakistan in the 1960s and early 1970s. She speaks fondly of Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, of the times when Begum Mujib would ask Zohra Tajuddin for some dry fish the latter cooked with finesse.

It must be said in Sharmin Ahmad's legitimate defence that while she does not fail to assess and acknowledge, in the broad historical sense, the place of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Bangladesh's history, she points to the huge anomaly that has remained in the tale of Bengali liberation through a systematic sidelining of Tajuddin Ahmad's role in the movement for freedom. Her belief is that of all those others who have always felt that the first step toward a gathering tragedy in post-liberation Bangladesh was taken when Bangabandhu compelled Tajuddin, his comrade in good times and bad, to make his way out of government. When that happened, the wolves closed in on the Father of the Nation, eventually taking the life out of him. And those same denizens of the dark forest would not let Tajuddin and his three Mujibnagar associates live either. The murder of Bangabandhu and the jail killing of the four Mujibnagar leaders will forever be a tale in infamy.

In Neta O Pita, Sharmin Ahmad makes a simple yet necessary point: If Bangabandhu was the inspiration in the rise and expansion of Bengali nationalism, Tajuddin Ahmad was the leader who conceived, conceptualized and led the nation to freedom through a strategically planned armed struggle. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's goal was the liberation of Bengalis. Tajuddin Ahmad's objective was a concretising of that goal, adding substance to it, and transforming it into reality.

In Bangladesh's history, therefore, Tajuddin Ahmad must be restored to the perch that belongs to him. Ignoring him would be tantamount to indulging in political immorality. That is Sharmin Ahmad's argument. One has little reason to disagree with her.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Executive Editor, The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments