The passing of a warrior

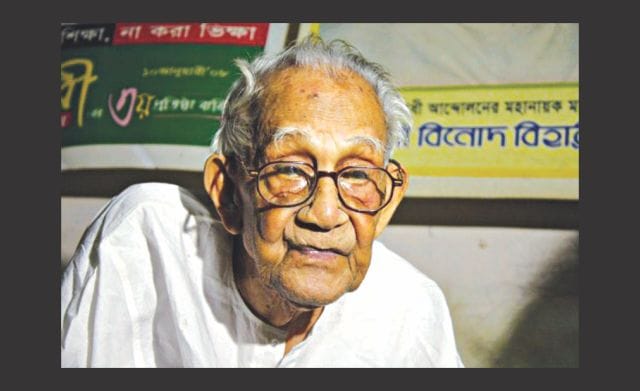

The passing of Binod Bihari Chowdhury is truly a descent of twilight on an era defined by patriotism and courage. His was a struggle marked by something epical about it. Now that he is dead, at age 104, it is time once more to recall the singular contribution he made to the history of this subcontinent in some of the most stirring times in its history.

The veteran revolutionary passed away at 11:00pm yesterday at a Kolkata hospital.

Binod Bihari Chowdhury was our last remaining link to a decisive part of subcontinental history. The sadness is in knowing, though, that what he and his comrades did between the years 1930 and 1934 in terms of arousing a sense of patriotism in all of us who wished to put an end to British colonialism in India is a reality we have almost confined to the sidelines of truth.

There is all the talk about the vivisection of India along communal lines in 1947. You hear arguments to this day about the crude manner in which India was broken into two, about who must bear responsibility for the perpetration of that tragedy. There are, too, animated conversations on what Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose might have achieved had he not disappeared from our lives. And you hear people in Bangladesh and West Bengal reflect loudly on the rap on the knuckles fate gave us through the untimely death of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das in 1925.

It is only a handful of people who recall the Chittagong armoury raid today in India and Bangladesh. Or you could suggest that the bright shining moment when Masterda Surjya Sen led his fellow revolutionaries into storming a powerful citadel of British imperialism on April 18, 1930 is an episode only students of history, at the academic level, sometimes refer to. But then, there was Binod Bihari Chowdhury to remind us of the seminal nature of that revolt against foreign rule.

He was barely twenty at the time, in the lofty companionship of Surjya Sen, of Preetilata Waddedar, Kalpana Dutta, Kalipada Chakrabarty, Ambika Chakrabarty, Makhan Ghoshal, Tarakeshwar Dastidar and so many others. These revolutionaries simultaneously raided the armoury, the police station and the telegraph office. The degree to which they cast aside their individuality in favour of their patriotism came through when they proclaimed a revolutionary government for a free India that was to wage a guerrilla war over the next three years. Surjya Sen spoke for his comrades thus: "The great task of revolution in India has fallen on the Indian Republican Army. We in Chittagong have the honour to achieve the patriotic task of revolution for fulfilling the aspiration and urge of our nation."

You could argue that the uprising was not destined to last, as eventually it did not. Surjya Sen and his men went on the run once it became clear that their action had fizzled out. And yet it was a revolt that sent shock waves among the various tiers of the colonial government. Masterda was tracked down, along with Tarakeshwar Dastidar and the young Kalpana Dutta. Surjya Sen and Tarakeshwar Dastidar were tried and hanged and their bodies were thrown into the Bay of Bengal. Preetilata Waddedar, wounded in the attack on the European Club in Pahartali in 1932, took her own life rather than be captured by the British. Binod Chowdhury, whose neck was pierced by a bullet in the course of the armed action, was captured and sent off to imprisonment in distant Rajputana. He survived loneliness and brutality and was eventually to be witness to the departure of the British from India. It was freedom, yes, but not of the kind he and his comrades had envisaged in the 1930s.

Binod Bihari Chowdhury chose to remain in Pakistan when many of his religious community crossed over to India in the aftermath of partition. It was a dangerous time, for the dreams he and his fellow revolutionaries had shaped in 1930 had splintered and parochialism had taken over. But then came a new moment in 1971 when, with his fellow Bengalis in East Pakistan, Chowdhury threw in his lot with the struggle for Bangladesh's freedom. The emergence of a secular Bengali republic in that year rekindled his faith in the ability of a nation to wrest its future out of its past.

In the final years of his life, Binod Bihari Chowdhury was witness to the rise and fall of politics, of dreams, in free Bangladesh. In a curious way, all this rise and fall in his expectations was but a mirror of the tortuous, boulder-strewn path history has traversed in our part of the world. It was a mirror Binod Bihari Chowdhury held forth in Ognijhora Dingulo, the memoirs through which he opened a new window to a study of the courage and conviction of the men and women who proclaimed a free India, however short-lived, in 1930.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments