Data sovereignty or data control?

The government is drafting a bill to make social media surveillance stricter and legal.

The purpose of the bill is seemingly benign -- protection of data generated within the country. Experts and social media users, however, fear that it will be less about protection and more about intervention into user data.

"We have no laws to take action against social media companies. We have no laws on data protection and nothing to protect the privacy of people…It is our ultimate goal to make social media companies follow the laws of Bangladesh."

"There are a lot of restrictions in holding offline dissentso the internet became the place wherepeople started coming to, but the small venue where people could express their opinions will not be there anymore. The law will dissuade me from participating in conversations to build my own country," said Dr CR Abrar, an academic currently operating as a part of Nagorik, a platform that works with civic rights and freedom of expression.

Most major social movements in recent times all began by mobilising online, before hitting the streets.

It is in this climate that the new data protection act is being formulated. One of the main features of this new law will be data localisation, meaning data about citizens collected by major tech companies will have to be stored nationally.

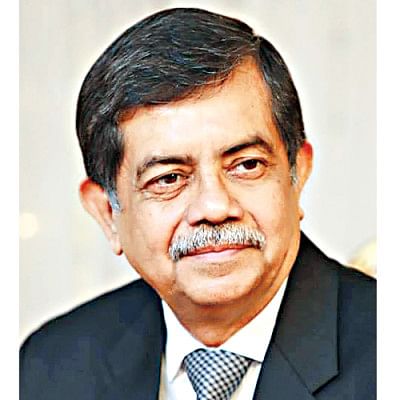

State Minister for Information and Communication Technology Zunaid Ahmed Palak confirmed to The Daily Star that they are indeed drafting such a bill. The ICT division is making it.

"The new data protection act will have legislation which states that foreign internet companies have to build data centres nationally and store user data inside the country," said Palak. "This will help us identify and take legal action against those spreading rumours and abusing the internet."

Palak said this new law is being drafted to make sure that citizens' data will stay inside the country.

Apart from tech companies, foreign financial institutions will also have to establish data centres in Bangladesh and will be brought under this legislation, he said.

"This new law is being drafted to make sure that citizens' data will stay inside the country."

"They will be obliged to follow the law, or else they will not be allowed to operate in Bangladesh," said Palak. "We are formulating this law in order to make sure that the data of the people stay within the country."

Mustafa Jabbar, minister of Post and Telecommunication, said this law is being drafted to fulfil three major gaps. "We have no laws to take action against social media companies. We have no laws on data protection and nothing to protect the privacy of people.

"It is our ultimate goal to make social media companies follow the laws of Bangladesh," said Mustafa Jabbar.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development's tracker, Bangladesh is one of the 25 countries in the world with no laws on data privacy and protection, so experts recognise the need for legislation in this area.

But experts fear that the new legislation is not focusing on the right thing.

"What the government is trying to do is called data localisation," said advocate Md Saimum Reza Talukder, a senior lecturer at Brac University who specialises in law, privacy and digital technologies.

Data localisation means that the physical device in which a person's data is contained, has to be located within the borders of the state that the person belongs to. Experts call this a double-edged sword.

"We have known cases, prominent cases where private conversations came out into the open. There are reasons to believe that these were not private organisations executing these leaks. National security is an important issue, but this is often capitalised upon to serve partisan interests."

"It is not clear whether the new draft will contain provisions for the government to get access to such physical devices or not. The worrying aspect of this is that if proper checks and balances are not described in the new draft, the government will have a chance to get access to personal information," said Talukder. He added that it is also not clear in the proposed law whether the government is allowed to seize the physical device where the data is stored.

"The government thinks that data is the biggest wealth of the future, and it is to protect this data that we are making this law," Palak argued.

Experts insist that the law should be about protecting user data from anyone -- including state actors.

"Data about me should be my property-- no law recognises this," said Talukder.

"We have known cases, prominent cases where private conversations came out into the open. There are reasons to believe that these were not private organisations executing these leaks. National security is an important issue, but this is often capitalised upon to serve partisan interests," said Dr Abrar.

"What we want are formal laws that ensure this privacy from the state," he said.

The dire need for a law that protects data from anyone can be understood if the existing Data Privacy and Protection Regulation 2019 -- which is not a law -- is scrutinised.

Experts say that in the regulation -- which provides a guideline for the application of the Digital Security Act's (DSA's) section 60 -- there are not enough checks and balances to protect data from state actors.

The regulation defines how citizen's personal data can be obtained, stored and used, but in many cases also exempts state agencies from complying with them.

For example, Section 21 (b) of the guideline allows government agencies to share private information among one another to investigate cyber incidents and identify individuals.

"There should be a judicial scrutiny to obtain such access," opined Talukder.

Talukder also pointed out, "The definition of the words 'national sovereignty', 'integrity', 'national and digital security' mentioned in Section 15 (a) needs to be given; otherwise these remain vague terms."

After all, vaguely defined terms have been part of the pitfalls of the DSA. During the formation of the law, it was repeatedover and over that the law will not be abused to target journalists and dissenters, but the reality is fairly different.

"Governments are pushing for data localisation under the guise of boosting the economy, tackling online harms, or protecting privacy. But the laws often do the opposite while making it easier to conduct surveillance. In countries that have poor standards of cyber-security, judicial independence, and data protection, data localisation presents a risk not only to privacy, but to the full spectrum of human rights," said Adrian Shahbaz, the director for technology and democracy at Freedom House, a Washington DC-based think-tank, which published a report last year called "User Privacy or Cyber Sovereignty?"

An example of a strong data protection law is the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation. Not only does it regulate how data can be accessed and who can access the data, but it also gives citizens the right to know what data is being collected about them, what will be done with it, how it will be processed, and finally, empowers the citizens to withdraw consent at any point in time.

India recently clamped down on Mastercard Inc and earlier, American Express, for not complying with local data storage rules. The Reserve Bank of India wanted data on Indian card payments to be stored inside India only. In July, Russia fined Google $40,000 for refusing to localise users' data.

The law that will force tech companies to store data locally comes at a time when the Bangladesh government has made the highest number of requests to both Facebook and Google for user data.

In 2013, the government had made only one request to Facebook for user data. Last year, that amount had risen to 541. As many as 76 of those requests dealt with criticism of the government.

For the past four years, the social media giant had given data for at least half of the requests.

Last year, only a little over half the requests made by the government followed the "legal process" while the rest were made under the category of "emergency disclosure".

The social media platform defines emergency requests as, "In emergencies, law enforcement may submit requests without legal process. Based on the circumstances, we may voluntarily disclose information to law enforcement where we have a good faith reason to believe that the matter involves imminent risk of serious physical injury or death."

Similarly, in 2014, the government had made only one request to Google regarding content, citing defamation, issues of national security and government criticism. Last year, that number was 87. A vast majority -- 74 of them -- dealt with criticism of the government.

The government will not just stop at formulating a data protection act -- they are also going to bring crucial changes to Bangladesh Telecommunications Act 2001 to widen the net for those involved in "anti-state activities", Mustafa Jabbar said.

The law will be amended so as to legally prosecute those participating in "anti-state" activities stationed abroad, in such a manner as if they are located inside the country. The DSA already allows for this under Section 4.

"However, this is still in draft stage and has not even gone to the law ministry," he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments