A life lived in stirring times

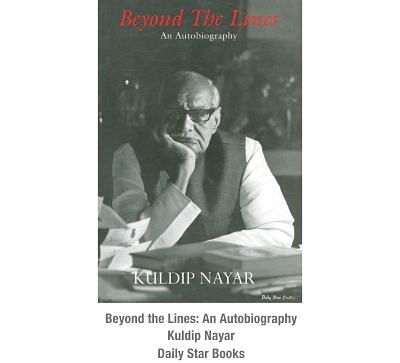

Note: It was a special privilege to be a discussant on the panel of the Daily Star Publications launch of the esteemed journalist Kuldip Nayar's book on 16 November, at 6.30 pm, at Bangla Academy. I was asked by the Daily Star representative to look at the literary aspects of the autobiography. I chose to focus on the 'Culture of Geography'.

One important aspect of cultural studies is what can be called the geographies (or, topographies) of culture: the ways in which matters of meaning are bound up with spaces, places and landscapes. The language of cultural studies is full of spatial metaphors, for example, 'fields', 'maps', 'boundaries', 'margins', borders', and 'networks'. Culture is also understood as plural, fragmented, and contested. It cannot be understood outside the spaces that it marks out, like national boundaries or regional territories.

The title of Kuldip Nayar's autobiography, Beyond The Lines, conjures up images of battle-lines, front-lines, border-lines, behind the lines, and of course, spaces and lives between the lines. Indeed, the history of the sub-continent is one of conquerors and the vanquished from the Persians and the Greeks, the Arabs and the Turks and the Portuguese, to finally, the British. The cradle of Indo-Gangetic civilization and the birthplace of the Indo-Sanskrit languages, with its sophisticated and unique Gandhara art and sculpture of Harappa and Moen-jo-Daro, has been the terrain of countless wars with its subsequent cyclical rise and fall of kingdoms and principalities.

Kuldip Nayar was in his hometown Sialkot and twenty-four years old, a lawyer (by professional training at Forman Christian College in Lahore), when on 12 August 1947, Partition was announced over the radio: “ It was like a spark thrown at the haystack of distrust. The sub-continent burst into communal flames. The north was the worst affected and to some extent Bengal (p.6). Nayar, now eighty-nine years old, has been witness to tumultuous events following Partition, and has recorded the political developments arising out of the hostilities among nations within the sub-continent. In the first chapter, 'Childhood and Partition', he tells us that he “stumbled into journalism by accident. My chosen profession was law,… but history intervened …, India was divided. Making my way to Delhi, I found a job in an Urdu daily, Anjam.†(p. 1)

Nayar confesses, with justifiable pride, that journalism has given him the opportunity to write what he considered to be correct. His autobiography reveals to us a man whose moral and social conscience, and deep belief in secular humanism, has its roots in his early life in the warm, nurturing enclosure of the joint family home in Sialkot. His grandmother was the “effective head†of the household, and though his grandfather was alive, he “took a back seat.†Nayar's grandmother was a “great one for astrology†and she had horoscopes of every child prepared by a leading pundit. One day, the pandit read Nayar's palm and predicted that the boy would read the malechh vidya (the language of foreigners, thereby meaning English), and travel a lot by udhan khatola (aeroplane). Nayar's mother, Puran Devi, was very particular about customs. She “really believed that antiquity gave them credibilityâ€(p.4). Although a practising Sikh, his mother celebrated both Sikh and Hindu festivals since marriages between Hindus and Sikhs were common in those days. Nayar frankly tells us, “It would be fair to say that we blended the traditions of Sikhism and Hinduism.â€

In the initial pages, Nayar ponders, somewhat philosophically and in a melancholy strain of lyrical prose, the eternal question of whether it is chance or choice which determines a man's path in life. He vividly recalls the image of his guardian spirit: “I have fond memories of my home, at Trunk Bazaar, a two-storey house with a garden at the back where there was an old grave which my mother said was the kabar of some pir (saint). The grave was like a family shrine where we prayed in our own way and sought refuge from the outside worldâ€(p.2). Later, Nayar reflects upon the influence of the “unseen guardian†upon his moral growth in his remarkable journey through the troubled times in the history of this region: “ I carried with me the blessings of the pir…. I feel he represents something spiritual; something akin to bhakti or sufism.â€

However, in the face of the reality of the horror of the reign of terror, the communal slaughter, following Partition, and the violent birth of Bangladesh accompanied by its own holocaust of genocide, Nayar is forced to wrestle with faith, with belief in a god, or in the possibility of god in man. Man's inhumanity towards his own kind, the persisting poverty in the region, and other social and class-based inequities still remain the focus of his writing, a quest to correct the failings within man and within societies. In the Preface written specially for this Bangladesh edition of his autobiography, Kuldip Nayar offers a poignant and prophetic prayer: “I have seen Bangladesh developing from the days when it was liberated. My contact with many people in Pakistan and Bangladesh is personal and I am proud to own the relationship. I believe that some day all the countries in South Asia will form a common union like the European Union (EU), without abandoning their individual identities, and this will help fight against the problems of poverty and to span the ever-yawning gulf between the rich and the desperately poor of all our countries. I am convinced that South Asians will one day live in peace and harmony and cooperate with one another on matters of mutual concern such as development, trade, and social progress. This is the hope I have clung to amidst the sea of hatred and hostility that has for far too long engulfed the subcontinent.â€

On the threshold of his ninetieth birthday, Nayar, the visionary, is still hopeful. Let his words lead us forward into the wide world of light and love and tolerance and equality and freedom. Let us expand our minds and hearts and embrace the other, the different, and the unknown.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments