Dhaka Stock Exchange: what next?

Prices in Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) nearly doubled in the half year to January, bringing back uncomfortable memories of 1996. In a few months to October that year, DSE more than trebled. The bull run seemed to have ended in November 1996, when the stock market rose by only 3 percent. Then came the fall -- stock prices halved in the next three months, eventually returning to the January 1996 level by the end of 1997. That kind of sharp rise and fall in asset prices, with little changes in the fundamental economic reality, is what we call bubble.

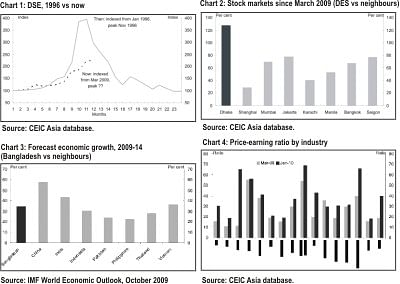

In February this year, DSE rose by 3 percent. Chart 1 compares the current bull run with that of 1996. In this chart, the horizontal axis shows number of months since the beginning of the bull run, while the vertical axis shows the DSE indexed to that beginning. Back in 1996, DSE started rising from January, so that's what the grey line is indexed to. Back in November 1996 (that is, 11th month of the run), DSE peaked at 395% of its January value.

Now, the market is indexed to March 2009, when the global asset markets reached the post global financial crisis trough. Since then, DSE had risen by nearly 125 percent by February 2010 (that is, the 12th month of the bull run). Is the current bull run over? Are we on the edge of a precipice? Or are the stock prices likely to have found a new plateau? Or are we in for a bigger bubble and a worse burst?

Asset price bubbles are often very difficult to identify before they burst. But in the case of DSE, there are strong (albeit not conclusive) reasons to believe that we are in the bubble territory.

Since last March, DSE has far outperformed other markets in the region (Chart 2). There are two reasons why one might expect Bangladeshi stocks to be attractive for global investors seeking emerging market bargains. First, with only a small proportion of stocks held by foreigners, Bangladesh remains a "hidden opportunity" for international investors. And second, Bangladesh weathered the global financial crisis relatively well, with respectable growth expected in the next half decade (Chart 3).

Another way to gauge whether we are looking at a bubble or a new equilibrium of high prices is to consider the price-earning ratio. All else being equal, high price-earning ratio means the stock has a high growth potential. But if price-earning ratio rises very quickly in the absence of any new information, then that might point to a bubble.

The weighted average ratio for the DSE has nearly doubled to 30 during the current bull run. But looking at the ratios in individual industries, it seems cement, information technology, services and real estate, and textile are the four industries where prices have really skyrocketed (Chart 4).

What's going on in these industries to justify such rises in the price-earning ratio? One possible story driving the real estate stocks is that there is a housing boom as well as a stock market boom. And this housing boom, along with the expectation that there will be an infrastructure boom in the coming period, may be driving the cement stocks. Similarly, one can argue that various "Digital Bangladesh" initiatives may well have been boosting IT stocks. And textile may have benefitted from the resilience shown by the export sector.

All these possible stories notwithstanding, there are stories of price-earning ratios reaching 70 or higher, suggesting nothing but "irrational exuberance."

What could be driving such an exuberance?

Monetary and tax policies may well have been contributing to it. With Bangladesh Bank's expansionary monetary stance, an undervalued taka, and strong remittance inflows fuelling a reserve surge, it's no surprise that the economy is awash with liquidity. This excess liquidity could be fuelling inflationary pressures in the goods market, with CPI inflation rising in recent months. And it is quite likely that the liquidity is fuelling bubbles in both housing and stock market. Add to this the measures introduced in the 2009 budget that allowed tax evaders to recycle black / undisclosed money.

And finally, there is a socio-cultural element of get-rich-quick that is driving the current herd mentality. Indeed, asset bubbles everywhere are driven by such behaviour of relatively unsophisticated small investors. In the case of Bangladesh, worsening law and order and red tape continuing to stifle entrepreneurship can only make a quick buck in the share market much more attractive than the difficult and risky investment in bricks-and-mortar venture.

Of course, bubbles always end badly and usually the retail investor suffers. This means the authorities need to act, and act fast. The thing with bubbles is, the longer they fester the bigger the usual aftermath is.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments