BANERJEE VS. CHATTERJEE 1945

THE TIMES OF SAIGON

I know of Capt. Banerjee, Military Observer, only because he wrote feature articles for the Times of Saigon, edited by my father, Bernard Drew, during the last four months of 1945. Capt. Banerjee had flown in with the 20th Indian Division from Rangoon to Saigon in September 1945 to accept the surrender of the Japanese forces. The Times was a flimsy, cyclostyled news sheet published daily by Allied HQ.

CAPTAIN BANERJEE ON THE INDIAN SOLDIER

One half-page article of Capt. Banerjee that catches the eye is head-lined: HOW THE INDIAN SOLDIER "LICKED" THE JAPS IN BURMA. The headline alludes to a remark made by General "Bill" Slim on a visit to Saigon and Capt. Banerjee supports this contention by reference to incidents of bravery he had himself witnessed in central Burma.

While the Indian regulars belong to a long military tradition, he writes, the wartime army has been mostly composed of volunteers, peasants who have shown cool and calculated judgement and won a number of V.C.'s. Fighting alongside foreigners, the Indian peasant has lost his sense of feeling inferior to them and is altogether "a new man".

BRITISH OFFICERS AND THE INDIAN ARMY

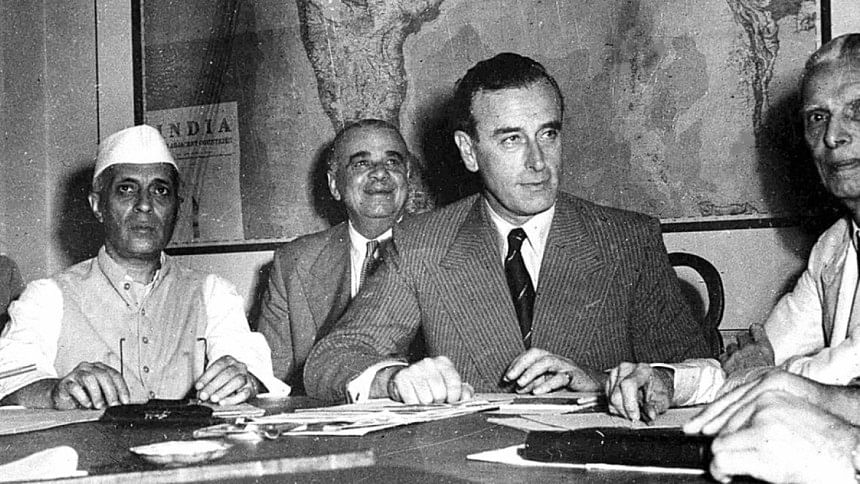

Capt. Banerjee's assessment, in an "embedded" news sheet, mirrors the views of the Allied High Command. The first issue of The Times reports Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia, after visiting P.O.W. camps, observing that Indians formed 70% of Allied ground forces in South East Asia and had resisted vicious attacks on their loyalty, preferring "death to dishonour".

Three months later Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India, makes the same point, saying that of the captured Indian P.O.W.s, 45,000 refused to join Subhas Chandra Bose's Japanese-allied Indian National Army and suffered 11,000 casualties as a result.

The paper does not report on the considerable number of those soldiers who did join the INA, only that Major General A.C. Chatterjee and other of their leaders are being captured in Hanoi and sent for trial in India not only for making war on the King but for torturing and punishing their fellow P.O.W.s who did not join the INA. The Times does report that by Christmas, their sentences to transportation for life have been remitted by General Auchinlech, C-in-C India.

Historians have to weigh in the balance whether it was the Japanese-allied Indian National Army advancing on India or the British-led Indian Army resisting them, if either, that played the greater role in determining and guaranteeing Indian independence.

THE VIEW FROM LONDON

Full self-government for India was announced by the newly-elected Labour Government in Britain immediately after the War ended, a fact relayed by the sixth issue of the news sheet. Prime Minister Atlee's panacea was of a free, undivided India based on the Cripps' proposals of 1942 with constitutional guarantees provided for minorities.

As M.N. Roy (the Bengali Radical Humanist who had been the one member of the Communist International besides Lenin to propose theses concerning the liberation of Asian peoples) had seen in 1940, when he offered his services to the (British-run) Indian Government, Britain would be a spent force after the war, unable (even if it wanted to) to hold on to India. And spent force it was.

One issue of The Times reports that Britain has "become a debtor nation for the first time in its history," Lord Keynes having returned from North America after negotiating a loan of £1,100,000,000 (a debt only finally paid back in 2006).

THE INTERNATIONAL STAGE

On the international stage, the paper records, a serious attempt was being made to hold together the wartime alliance of the Big Three (the Soviet Union, the United States of America and Great Britain) and guarantee a new world order.

Foreign Ministers of the three Powers agreed to work together to establish the peace in China and in Korea. Plans were made to establish the United Nations Organization in London, and separate bodies were quickly formed to deal with such matters as control of atomic power and food distribution on a global scale.

So what was the position of Britain? For a while anyway, the new Labour Government looks to be an ideal mediator between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. With Churchill out and Atlee in, abroad as at home, it promises a new deal for ordinary people.

In late September, Jack Lawson, Atlee's close friend and Minister of War, on an extensive tour of the Far East, is quoted by official SEAC radio in Singapore as saying that it is not the policy of the new British Government to support the French in Indo-China or the Dutch in the Netherlands East Indies.

This is in line with American attitudes towards European colonialism in Asia. The late President Roosevelt had sent Special Forces to support Ho Chi Minh in his campaign to overthrow French rule in Indo-China. American sailors refused to help Dutch women and children being released from internment in the Dutch East Indies: we were on the side of the Indonesians, they said.

A NEW WORLD ORDER?

Towards the end of 1945, there was an editorial in the Times welcoming Ernest Bevin's arrival in Moscow for a Foreign Ministers' conference designed to clear up "the terrible mess" the world was in. The editorial warned its readers that it is a world they have made because they have not developed the patience to understand other people's points of view.

The final editorial of the Old Year bade a heartfelt goodbye to a year in which, at the end of "the greatest slaughter of all time," all had been stunned by the effect of two small bombs. One good effect of the war, it added, had been the responsibility given to young men that they would never have had in a lifetime of peace. So it was now up to them to ensure that the century of the Common Man passes from phrase to fact.

This post-War possibility of a new World Order in favour of the Common Man suddenly vanishes. President Truman makes a decision not to support those anti-colonial movements for independence that include any form of Communist constituent. This reversal of Roosevelt's policy on colonialism was partly determined by his decision to back western European countries in their fight against Communism within (Italy, France and Greece all have strong Communist Parties in repudiation of Fascism).

India, its independence already conceded, might have had hoped to be free of the Cold War divisions that followed upon this, notably in Korea and Vietnam. Instead, as we know, it suffered the appalling trauma of Partition and its constituent countries, notwithstanding India's place in the Non-alignment movement, suffering from the way the Big Three were able to play upon internal divisions.

At least before the 20th Indian division left Saigon, in a football match refereed by my father, the Other Ranks beat the Officers 2-1. The Common Man won that one. How about that?

John Drew reports on a bit of family history that marginally overlapped with India's.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments