From Under the Rubble

The nine-storied Rana Plaza, housing six ready-made garments (RMG) factories, collapsed on 24th April 2013 at 8.57 am, after generators had kicked-in following a power-cut. Khowas Ali, a small-time trader in Savar and one of the first on the scene, headed a rescue effort using bamboo from the rooftop of next-door RS Plaza. Later he was able to arrange basic instruments to make holes from RS Plaza into different floors of the collapsed building, pulling out those trapped inside. He, and others like him, a motley crew of strangers, worked for 21 days at a stretch, day and night, with minimal sleep or food. The fire-service, army and police, as well as other organisations on the ground, were to give them much-needed support.

Reflecting on the grief and pain of a year ago, what undeniably shines through is the extraordinary compassion and bravery of these local rescuers, who put themselves at huge personal risk, to save 2,550 of the 3,639 in the building. Ironically, many of these trapped would not have survived if the tenets of international disaster protocols had been abided by. These rescuers entered into treacherous, narrow spaces, many only 15-20” high, to save strangers. The stench of death was overpowering, with poor visibility due to dust, insects, mosquitoes and maggots, and the heat stifling, - victims who had survived more than eight hours had stripped themselves bare. Each rescue involved hours of painstaking effort in claustrophobic conditions, by those with no knowledge of even basic first aid techniques. Rudimentary instruments were used to break into different floors and cut beams. Mobile phones helped locate people. The nation rallied around with unprecedented support. Hundreds of organisations, among them Red Crescent, BILS, Sajeda Foundation, Anjuman Mofidul Islam, Enam Medical College, Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed, along with thousands of individuals, helped the rescue effort – providing money, meals, food, fuel, water, saline, oxygen, generators, torches, basic tools, medical and other support.

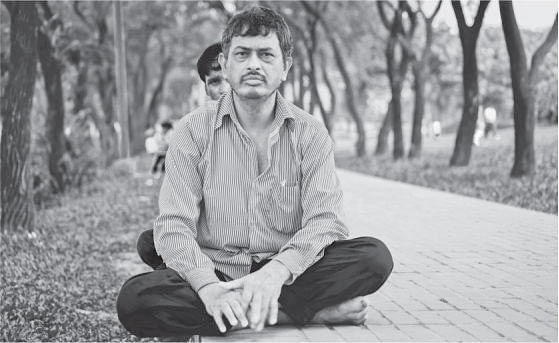

While Khawas Ali led efforts at one side, Yunus, a cook, entered the building trying to find his wife, and with Jinnah Ali, the owner of a local laundry, he brought out over 200 people alive. Shopon, a small business owner who entered the rescue tunnels after a random stranger begged him to help look for his daughter, remained for 21 days, along with computer-businessman Shujon, who made the first list of people involved in the rescue operation. Afroza, a sewing operator from a nearby factory, stayed on after searching for her brother-in-law, and the only woman who entered the rescue tunnels, keeping track of rescuers, preparing oxygen tanks, and tying tourniquets on site. Authorities initially tried to block her entry but gave in when she asked them, 'If I don't go in, will you?' Muhit, a student, prepared and cared for dead bodies, playing an invaluable role helping relatives identify their loved ones, sleeping next to rotting corpses, in the nearby Adharchandra High school. Daroga Ali along with raajmistri Rafiq, handled hundreds of corpses. Kaikobad the young engineer who suffered severe burns after a mammoth unsuccessful rescue attempt to save a young woman, died in Singapore of his injuries. The young rescue workers sawed off limbs, on instructions via mobile phone from doctors outside. Many of the rescuers still harbour feelings of guilt at not being able to save more lives, of wonder at finding life in a pile of bodies and of recurring nightmares of screams asking for help.

The death toll of 1, 142, included two rescuers. Out of the 322 remains, 210 have been successfully matched with relatives by the Disaster Victim identification software, CODIS, donated by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), at the DNA lab at Dhaka Medical College hospital. The Prime Minister's special fund raised about 120 crore Taka, 22 crore of which has been disbursed. Primark paid nine months worth of salary to all in the building, and has fixed a compensation package. The Bangladesh Garments and Exporters Association (BGMEA) spent 44 crore taka on compensation, treatment, rescue and rehabilitation including 2 crore donation to the PM's fund. The ILO operates a compensation fund of USD40 million. There have been numerous initiatives to help with treatment and rehabilitation. However, the compensation process has been criticized as being slow, non-transparent, uneven and unsatisfactory.

Following the collapse, SAFE (Safety Assistance for Emergencies), a local trust, has facilitated the setting up and training of an informal network of rescue workers from Rana Plaza. Having shown obvious aptitude and intrinsic empathy, these rescuers are now being trained in Basic and Advanced First Aid, fire safety and building evacuation, with psychological support from Naripokkho. The team have been volunteering at recent fires in factories in Savar. Their dedication and humanity are a beacon of hope rising from the rubble – a testament to the spirit, strength and resilience of the best of Bangladesh.

One year on from the tragedy, is it business as usual, or has there been a paradigm shift regarding attitudes to safety in Bangladesh? In the RMG industry there has been much-required scrutiny of safety issues, with sweeping changes to improve safety in the industry as a whole. Conditions have actually been steadily improving in the last decade with arguably 2,200 out of the 3,500 functional factories already compliant with international standards for safety, many having regular third party audits before the Rana Plaza incident. Structural integrity of buildings has now been added to audit protocols. The Labour and Employment Ministry recently carried out inspections of all factories, looking at over 50 criteria, and found 300 out of 3460 needing rectifications. Safety initiatives like the National Tri-partite Action Plan (NAP) on Fire, Building & Electrical Safety (under the ILO), Bangladesh Accord on Fire & Building Safety, with over 150 foreign brand signatories, mostly European, and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, with 26 mostly North American Brand signatories, are underway; the latter two initiatives covering 3.3 out of 4.4 million garment workers, with NAP covering the rest. In the zealous drive for improving standards, there are concerns that buyers are pulling out of factories prematurely in some cases. Given that 47 percent of the total number of factories (employing over 2 million workers) are in shared or converted buildings, the livelihoods of thousands may be in jeopardy, even though the factories may have internationally acceptable safety standards. The RMG industry pays the highest comparable wages in Bangladesh, and remains the best option for employment for women. The minimum wage of the industry was raised by 78 percent on 1st December, without a concomitant increase in prices by most buyers. An estimated 500 factories have had to close for political unrest, non-competitiveness due to raised salaries, and compliance issues.

The collapse aftermath also showed that Bangladesh is grossly unprepared to tackle an urban disaster, natural or man-made, highlighting the need for a clear coordinated urban disaster protocol, with standing government orders, and a ready, trained volunteer pool.

Unlike the RMG industry, the government does not seem to have taken on board safety concerns with regards to building construction with the same urgency. Insiders say that 95 percent of buildings in Dhaka city violate the National Building Codes, with no indication of any real change in approval and implementation process. The collapse was due to corruption, party political intimidation, cronyism, and violation of regulations (illegal landfill in a former pond, building more floors than approved, using sub-standard cement and rods, and generators placed on every floor providing perfect resonance to cause the collapse), with little regard for human life. Perhaps the real tragedy will be if we do not learn from mistakes; there have been no marked efforts by the government to ensure proper building construction, despite having seen the devastation that can occur when buildings are not built safely.

The writer is Chairman of SAFE and a member of Naripokkho. She works in the RMG industry.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments