Whose blame is it anyway?

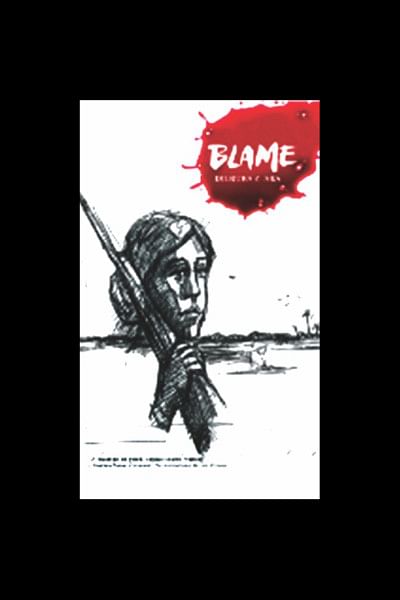

Blame' is a noun. 'Blame' is a verb. As a title of the novel, the word stands alone on the cover page, and as readers we do not know whether the story that we have in our hands is about an act of blame or about being blamed. Dilruba Z. Ara, who teaches Linguistics at a Swedish University, explained the parts of speech of the title of her second novel during its launch at the Dhaka Lit Fest in November. The personal narrative is actually more about the split humanity that accompanied our liberation war as an atrophy than a split grammatical item.

If war is a game, blame is a game too. Blame game can both be the cause and effect of a war. Blame game is particularly significant in the context of our liberation war in which a systematic programming and erasure of memory by successive governments was enacted. While history mostly concerns itself with the Who's Who in the war almanac, a fiction may focus on the imaginary other as the representative of the silent majority who sacrificed and suffered during the birth of a nation. Dilruba Z. Ara's novel is one such platform where the coming of age of a female protagonist coincides with the becoming of the nation.

The three-part novel begins in 1965 when Laila is still a teenager who is attracted to her poor Hindu neighbor Santo. The grownups as well as the growing communal tensions across the country constantly remind Santo and Laila that they are living in a changed world where it is impossible to have friendship across the religious divide. They cannot swim in the village pond as water too can be made impure by religion. Laila cannot invite Santo to the cock-fight organized by her family, the aristocratic Kazis. Her voice is subdued by the machismo of her brothers, father, uncles, and even a would-be suitor. Bullied by the narrow vision of patriarchy, represented by the closed eye shaped courtyard of the Kazi twin-houses, Laila can at most secretly receive a parrot with a broken wing from Santo and rear it in a two-chambered cage. The symbolism of Dilruba Z. Ara's novel comes naturally: the green parrot with its red ringed neck is the dream of a non-communal Bengal (foreshadowing the flag of a nascent state) that is kept in a two-chambered cage; rather, Pakistan a country with two wings. The grownups debate why being pure Muslim is important in Pakistan. The Hindu family finds it no longer safe in Chittagong; they changed their names and moved to Dhaka. Santo's father even started growing beards.

The second part of the novel covers just two years: 1968 and 1969 when the call for autonomy was becoming stronger under Sheikh Mujib's 6-point demand. Laila finds herself in the thick of things when she comes to study in Dhaka. She could come as she was under the care of her uncle with whose son she was supposed to be married. Laila soon moved to the dorm where her inner passion for freedom was ignited by a group of like-minded men and women who could think beyond conservatism and think of humanism. Dhaka seems to be conducive to free thoughts where her cousins have also become revolutionaries.

Part 3 is the longest as it tells the tale of the war. The young girl by now has become a freedom fighter. So has her cousins, her childhood friend Santo and his sister Gita. But the plot moves to Chittagong after spending its incubation period in Dhaka. The war makes everything convoluted. War causes the various characters charter the limits of heroism and cowardice, love and hatred, passion and possession, sanity and insanity, loyalty and betrayal, innocence and experience, and above all, freedom and slavery. The agony that we go through, as readers of Dilruba Z. Ara's novel, is the pain of knowing and not knowing. The realistic account of the book helps us anchor the historical narrative. As informed audience we identify some of the events, motifs, or even anecdotes. Still the shock is too much to bear.

The afterword comes to validate the authenticity of the plot. The power of this chronological linear story lies in its story. A novel is primarily, as someone once said, story, story and story. Indeed, this is not a postcolonial novel trying to redress the past or a postmodern fiction that questions the validity of truth. I find the novel a straight forward historical fiction that claims the authority of being authentic. As a reviewer, I do not want to give away the story, but I welcome you all to read about a fringe narrative that is important in understanding the making of our national psyche as Bengali. It is a story that is brutally honest and honestly brutal. I can only ask you to read it and come to your own opinion about the book.

The reviewer is an Academician.

He can be reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments