Welcome to surreal Pakistan

Translated by Bilal Karim Mughal

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

—William Wordsworth

When after a long journey through mountains, valleys, villages and hills; I saw Deosai for the first time, it struck me as if Wordsworth wrote the poem for Deosai.

It's not an exaggeration — really, one should visit and see for themselves. The Deosai National Park and the Sheosar Lake are the literal personification of Wordsworth's poetry.

A hundred years ago, humans would consider uninhabited and far-off places too frightening to visit. They would refer to such deserted and forsaken lands with strange names which reflected their fear of the unknown.

Things are changing now. In this age of industrialisation and commercialisation, with scores of amusement facilities offered in the metropolis, the number of people visiting these forsaken lands in the northern areas of the country is increasing.

Humanity is progressing in intellect, but deep inside, the peace of soul and mindfulness appears to be missing which people are not seeking in these deserted lands. If one is in search of solitude and wilderness, then why not visit Deosai?

Deosai is the combination of two words 'Deo' (giant) and 'Sai' (shadow). For centuries, it is believed that this place is haunted by giants, thus the name 'The Land of the Giants' came into being. The weather is quite unpredictable here, sometimes it starts snowing in summer. Sunlight and clouds seem to play hide and seek here, with the sun shining one minute, and overcast in the next.

This area remained uncrossable for ages due to abundance of variety of wildlife here. Icy winds, thunderstorms, and presence of wildlife make it impossible to dwell here even in this age, that's why Deosai is mostly uninhabited.

Nomads from Kashmir pass through the Deosai plains with their herds, it is their path of choice since centuries.

Deosai has a deafening silence, a silence spanning over centuries. The silence is so deep that one can hear his own heartbeat, unless a marmot's whistle fills the valley.

Deosai is located on the boundary of Karakoram and the western Himalayas, and at no point is it less than 4,000 metres above sea level. It remains covered with snow for eight months. The rest of the year, it hosts a range of beautiful flowers of all hues and colours, but not a single tree is found in this plateau spread over 3000 sq. km.

There are several springs in Deosai, brimming with trout fish serving as food for locals and bears alike. 5000 meter high mountains in the backdrop, wildlife dwelling in these mountains, clouds so low that one can almost touch them, Himalayan Golden eagles flying between the clouds, and a strange fragrance in the atmosphere which probably is a mixture of brown bears, red foxes, white tigers, and naughty marmots—this is the real beauty of Deosai.

A road from Skardu Bazaar turns to the Sadpara village. From this curvy road, Sadpara lake seems so beautiful, that the onlookers forget to blink. Soon comes the Sadpara village, where the local children have conspired with nature to stop the vehicles.

A spring flowing through the road has broken it, slowing down the cars, and as soon as a vehicle slows down, local children stop them to sell cherries and other local fruits.

When the village is left behind, the road becomes uneven, and increasing height puts pressure on ears. High mountains on one side, and depths on the other side—it is enough to disrupt the heartbeat of a first-time visitor. But when you are done with the journey, such a scene awaits you, which can neither be described in words, nor can it be entirely captured in photographs.

Crossing the bridge at Barra Paani, there is a road which leads to Sheosar Lake. Sheosar in local language means 'andhi' (blind). This lake is one of the highest lakes in the world. The deep blue water, with snow-covered mountains in backdrop, and greenery with wild flowers in foreground offer such a view in summers, that one is left amused for the rest of his life.

If the weather is clear, the killer mountain Nanga Parbat's snow-covered peak can be seen easily. And if the lake is calm, then Nanga Parbat's image appears in the lake as if someone has dissolved white paint in the blue waters. This lake is the heart of Deosai.

Very few people have risked their lives to cross this plain during the winters. I wanted to see Deosai in November, when there would be no tourists.

I should have turned back to Skardu that day from Sadpara Check Post. Army vehicles were returning half-way, waving to me to turn back due to rough weather. But I was very excited to see Deosai, my gut feeling was begging me to not turn back.

The punishment for this stubbornness was that the jeep track had completely disappeared due to snow, increasing the risk, and pushing the jeep with snow chains in the tires. Tires would bury deep in the snow, and at several spots, the snow had turned into ice, causing me to slip.

That entire day was spent pushing the jeep, digging the snow, and praying to God for safety. Nature doesn't reward you easily, it has a price. I was dead-tired at the end of the day, but the beautiful scene ahead of us was worth it.

We saw a brown bear and her cub a little before Sheosar Lake. Visibility was not too good due to snowfall, but it was a heartening sight anyway. I didn't have a lens of above 200mm focal length too, so I just took a binoculars and enjoyed watching them. In the meanwhile, 3 Himalayan red foxes passed by our jeep.

Snowfall had intensified as we reached Sheosar Lake. The visibility couldn't have been more than 20 meters. I was inside the jeep, appreciating the nature in its roughest form. Smell of bears spread in the atmosphere; there was no one else there other than me, my driver, and nature at that time.

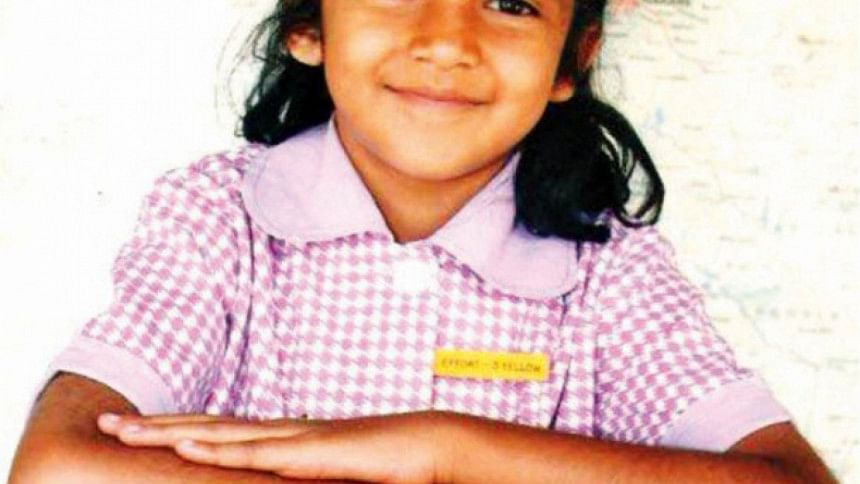

In the extreme cold weather and a tiring day, we crossed Deosai and reached Chillam Check Post. Registered myself at the check post there and hit the road to Astore. A little girl was going to her home with her two sheep. Upon hearing the sound of the jeep, the sheep went off the road. The little girl turned back and smiled at me; the day's tiredness just vanished away.

The sun was setting behind the mountains as we went from Chillam to Astore. I saw an old man sitting beside a grave. He had just wiped his tears while the Pakistani flag was hoisted at the grave.

I moved forward to greet him and he asked: "Neeche se aaey ho?" (Have you come from below?). That is how the mountain dwellers call the tourists. I responded positively. After a random exchange of words, I asked him about the grave.

He said: "This is my son's grave. I am a retired soldier, and now labour to keep the life going. I put him in a college in Rawalpindi with my pension, savings, and labour. He was my only child. While coming to Astore from Pindi, he was off-loaded from the bus, identified, and killed for his religious views."

I was left without words. A deafening silence had enveloped the valley.

After a brief pause, he continued: "his grave lies on the way to work, so I stop by for a few moments to pray here everyday."

I didn't know what to say. While leaving, I once again looked at the Pakistani flag, but this time, it felt as if the crescent and the star had turned blood red.

The northern areas of Pakistan are beautiful, they please our soul. But at the same time, we should be conscious of the miseries of the local people. All of the ecstasy of the journey had collapsed on hearing the tragic story from the old man. I couldn't help but weep inside.

When the jeep started moving, the driver turned on the tape-recorder. A ghazal broke the eerie silence inside the jeep. Though it was freezing cold outside, here I felt a fire within me.

Syed Mehdi Bukhari is a network engineer by profession, and a traveler, poet, photographer and writer by passion.

By arrangement with Dawn, an Asian News Network (ANN) partner.

Comments